Perspectives of general practice nurses, people living with dementia and carers on the delivery of dementia care in the primary care setting: potential models for optimal care

Caroline Gibson A B * , Dianne Goeman A C , Constance Dimity Pond D , Mark Yates B E Alison M. Hutchinson F GA

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of dementia requires a change in the organisation and delivery of primary care to improve the accessibility of best-practice care for people living with dementia and their carer(s). The aim of this study is to describe potential models of dementia care in the primary care setting whereby the nurse plays a central role, from the perspectives of nurses working in general practice, people living with dementia and carer(s).

Data from two qualitative semi-structured interview studies were pooled to explore the views of nurses working in general practice, people living with dementia and carer(s) on potential models for the provision of nurse-delivered dementia care. Data were thematically analysed. Six carers, five people living with dementia and 13 nurses working in general practice took part in the study. The data used in this study have not been previously reported.

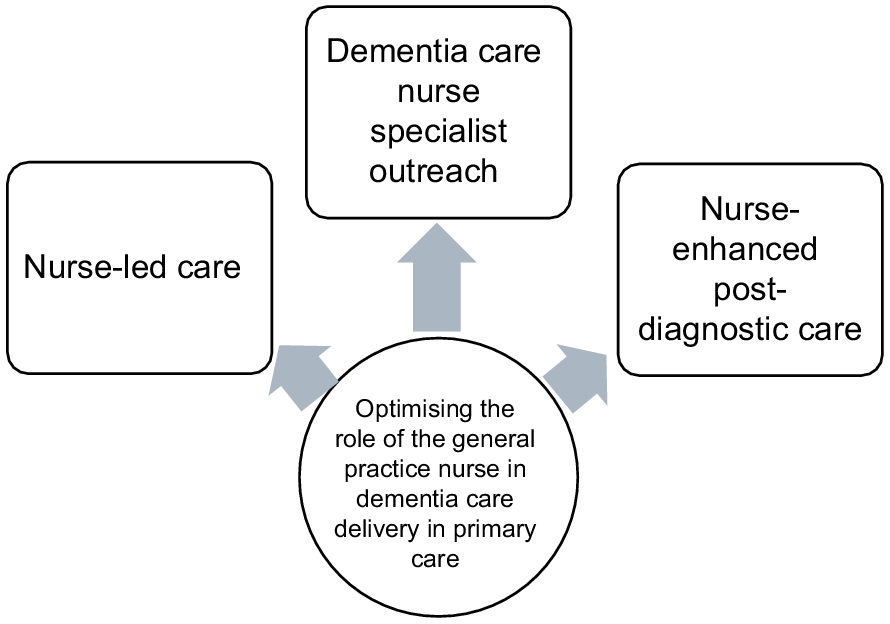

Three themes describing nurse-delivered models of care to meet the healthcare needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s) were identified: nurse-led care, dementia care nurse specialist outreach and nurse-enhanced post-diagnostic care.

This study describes three potential models of dementia care delivery by the nurse in general practice. These findings can be used to guide the implementation of new models of care that integrate the provision of dementia care by nurses within interdisciplinary primary care teams, to better meet the healthcare needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s).

Keywords: carers, dementia, general practice, nurse-led care, nurses, people living with dementia, primary care, qualitative.

Introduction

As the prevalence of dementia increases there is a growing global focus on a more proactive approach by primary care practitioners in the provision of a timely diagnosis and the management of dementia (Aminzadeh et al. 2012; Mansfield et al. 2019). However, primary care for people living with dementia is often fragmented, uncoordinated and unresponsive to the needs of people with dementia and their carer(s) (Prince et al. 2016). A significant change in the organisation and delivery of primary care is therefore required to improve primary care access and continuity of best-practice care for people living with dementia and their carer(s) (Helmer-Smith et al. 2022).

Nurses working in general practice, henceforth referred to as general practice nurses (GPNs) are an existing workforce within primary care and increasingly being utilised to expand the capacity of the primary care workforce in the management of long-term conditions (Halcomb et al. 2019; Johnson et al. 2024). Similar to GPs, GPNs are highly skilled generalist health practitioners who encounter and manage a wide range of presenting conditions in primary care (Norful et al. 2017; Swanson et al. 2020). A key element of high-performing primary care is team-based care (Ghorob and Bodenheimer 2015) in which both the GP and GPN play a collaborative role in provision of care. Complementing the GP bio-medical model of care with its emphasis on symptoms and their management, a nursing model of care contributes a bio-psychosocial approach to patient care (Eley et al. 2013; Terry et al. 2024). GPNs have a role in the care of people living with dementia and their carer(s) (Phillips et al. 2011), particularly in the earlier stages when the emphasis of care is optimising function and social engagement and supporting the carer role (Dröes et al. 2017; Bamford et al. 2023). GPNs believe that they were better suited than the GP to address the functional and social healthcare needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s) and should be included in a team-based approach to care (Gibson et al. 2021). People living with dementia and their carer(s) also perceive that the GPN has a role in the provision of dementia care as they are perceived as being able to spend time with them and listen to their needs (Gibson et al. 2024a), key elements of person-centred care that are fundamental to best-practice dementia care (Fazio et al. 2018).

To support the integration of the provision of dementia care by GPNs, within interdisciplinary primary care teams, there is a need for the roles and responsibilities of the GPN to be clearly defined within new models of care (Supper et al. 2015). A ‘model of care’ is an overarching design for the provision of a particular type of healthcare service (Davidson et al. 2006) and includes defined guiding principles, service aims and structures and effectiveness in achieving desired outcomes (Minghella and Schneider 2012).

This innovative paper builds on findings from two qualitative studies exploring the GPN role in dementia care. The perspective of the GPN (Gibson et al. 2024b) and those of people living with dementia and their carers (Gibson et al. 2024a) (henceforth referred to as care recipients) are brought together in this paper to describe potential models for optimal GPN care.

Methods

Research aim

This study aimed to describe potential models of dementia care in the primary care setting whereby the GPN plays a central role, from the perspectives of both the GPN and care recipients.

Study design

A social constructionism theoretical lens was applied to address the research aim. This theoretical approach is concerned with the processes by which people describe, explain or account for the world in which they live (Crotty 2003). The data from two qualitative semi-structured interview studies (Gibson et al. 2024a, 2024b) were pooled to explore the views of both care recipients and GPNs on potential models for the provision of dementia care by the GPN. The data used in this study has not been previously reported. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist (Tong et al. 2007) was used.

Participants

Twenty-four participants were included in this study (11 care recipients and 13 GPNs). Of the eleven who were care recipients, five (45%) participants identified as living with dementia and six (55%) as carers (Table 1). The majority (64%) of care recipients were female. All participants, excepting one carer, were aged 70 years and over. The majority of care recipients (82%) lived as a dyad. All care recipients had engaged with a GPN within the last 12 months.

| Carer (N = 11, n = 6) | Person living with dementia (N = 11, n = 5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 50–59 | 1 | 0 | |

| 60–69 | 0 | 0 | |

| 70–79 | 4 | 4 | |

| 80+ | 1 | 1 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | 3 | |

| Female | 5 | 2 | |

| Living arrangement | |||

| Alone | 1 | 1 | |

| As dyad | 5 | 4 | |

| Living location | |||

| Geelong (suburban area) | 3 | 2 | |

| Ballarat (suburban area) | 3 | 3 | |

| Length of time dementia noted by carer | |||

| Less than 2 years | 2 | ||

| 2–4 years | 1 | ||

| Greater than 5 years | 2 | ||

| Interaction with GPN | |||

| Care plan and or health assessment | 4 | 4 | |

| Brief encounters e.g. immunisations or wound care only | 2 | 1 |

The 13 participants who were GPNs (Table 2) were all female and aged between 30 and 69 years. All the GPNs had experience in chronic disease management. Ten (77%) GPNs self-reported having attended dementia training, although the type of training was not specified.

| (N = 13) n | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 30–39 | 5 | |

| 40–49 | 2 | |

| 50–59 | 4 | |

| 60–69 | 2 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 13 | |

| Years of primary nursing experience (years) | ||

| 2–5 | 2 | |

| 6–10 | 7 | |

| Over 10 years | 4 | |

| Chronic disease management experience (yes) | 13 | |

| Attended a dementia training program (yes) | 10 | |

| Location of primary place of work as PN | ||

| Vic | 4 | |

| NSW | 2 | |

| Qld | 3 | |

| SA | 1 | |

| WA | 3 |

Recruitment of the study samples has been previously reported (Gibson et al. 2024a, 2024b).

The pooled study data (Gibson et al. 2024a, 2024b) consisted of 19 interviews. The 13 GPNs were each interviewed using the Zoom on-line platform (Banyai 1995) during February and March 2023. Care recipients participated in face-to-face interviews in January and February 2024 in their own homes. Eight care recipients participated as a dyad (eight interviews in total). Two carers and one person living with dementia were each interviewed individually (three interviews in total). All interviews were conducted by the primary researcher (CG), a PhD candidate and a registered nurse in primary care. All participants were aware that the study was part of the interviewer’s PhD research. The interviews ranged between 21 and 61 min, with an average length of 40 min (total minutes = 775 min). The guiding questions used in the interviews have been previously published (Gibson et al. 2024a, 2024b).

The data from two previous qualitative studies were combined, reanalysed and coded using Braun and Clarke’s six steps of thematic analysis; familiarisation, generating codes, constructing themes, revising and defining themes and reporting (Braun and Clarke 2006). Three study authors (CG, DG and DP) reread the transcripts and met to develop the new coding framework according to deductive codes identified from the study aim. The transcribed interviews and codes were entered into NVivo11 qualitative software (Lumivero 2023). CG then inductively coded all data by systematically going through each transcript, highlighting meaningful salient text. Relevant codes and themes were constructed. When new concepts emerged, CG, DG and DP met to discuss. Any discrepancies were resolved via consensus. If consensus could not be reached, two study authors (MY and AH) reviewed the data. The transcripts were re-examined in the light of the review. Refer to Table 3 for an example of the coding tree.

| Theme | Example codes | Example text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia care nurse specialist outreach | Nurse with advanced knowledge and skills Refer to specialist Increase patient accessibility to best care resource for generalist nurse | Where if you have questions or you feel unsupported you have got somewhere you can turn to ring and to ask, what should we do in this situation. (GPN 4) Doctors make referrals to other doctors because they know this doctor is going to meet your needs better, why don’t we have the same system for nurses. (GPN 6) | |

| Nurse-led care | Nurse should be ‘front and centre’ Primary contact make an appointment directly with the nurse Nurses have time to spend with person | … the doctors too busy, it is really not worthwhile … it is nice to have someone to talk to about it… the nurse is someone you could talk to … more approachable. (Dyad 1, PLWD ) | |

| Nurse-enhanced post-diagnostic care | Integrated care Better at giving information than doctor Assure will be supported at beginning Give hope | Nurses have got a golden opportunity to bridge that moment from diagnosis, to empowering people to take charge of their lives, because in that moment of diagnosis, they’re out of control. (Carer 2) |

Results

Themes

Three broad themes describing potential GPN models of care to meet the healthcare needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s) were identified (Fig. 1). The three themes, nurse-led care, dementia care nurse specialist outreach and nurse-enhanced post-diagnostic care are described below:

There was strong agreement between GPNs, people living with dementia and carers that the nurse should be ‘front and centre’ in optimal dementia care provision. The study participants described a model of care in which the nurse was the primary contact for the patient. The nurse would provide information, connect the person with services and provide regular follow-up and monitoring.

… in general practice wouldn’t it be cool if we could have the practice nurse, as the top of the team and they organise the different people in place. That might be allied health services, it might be home health carers, it might be whoever. It would also include their family care if they’re the ones supporting. I mean, I think that that would be a really cool way to do it where we would be the first stop. We would make that care plan, plus we’d implement these different people to help the person living with dementia, then review and say, okay, how’s it going? How’s the care plan? (GPN 6)

Contact with the GP was not determined to be required for the patient to engage with the nurse, however, it was deemed that the GP should be involved for medical concerns if needed.

It was agreed that care recipients should be able to:

... make an appointment with the nurse. You don’t need to have the doctor involved. The nurse can actually just say well, these are the steps that we would need to do.. Then you bring the doctor in as needed rather than the other way around. (GPN 9)

Being able to make an appointment directly with the nurse rather than the GP was seen as not just improving accessibility to appropriate care but also being a more efficient use of resources including the GP’s time.

… there has to be a change of how a practice is run. I think there is a brilliant opportunity for a nurse to be front of house … They would give the information. They would do the assessment and incorporate the family as well. Then when they’ve got a problem, instead of ringing up the practice to see the doctor, they’ll ring the practice to speak to the nurse to get support. That will be marvellous for medical clinics because it’s going to mean that people are coming to the practice to get the information that they need. You would think that it would take some time off the doctor too, that he wouldn’t have to spend as much time. (Dyad 2, Carer)

Although it was thought that all GPNs should have a basic understanding of dementia and how it impacts on a person living with dementia and their carer(s), study participants did acknowledge there was a role for a nurse with dementia expertise.

… in a perfect world, everyone would be trained in how to deal with everyone with dementia, and that’s not going to happen. We’ve got Nurse so-and-so here. She’s a specialist in this area, and she’s going to be able to talk through with you some practicalities but also some things that you may not have thought about. You need someone to actually sit down with you and explain it all to you … someone who has the knowledge. (Dyad 2, Carer)

Nurse study participants discussed the value of being able to link a patient with specialist services in much the same way doctors do when expert input is needed.

I often think to myself how nice it would be, doctors make referrals to other doctors because they know that this doctor is going to meet your needs better. But why don’t we have the same system for nurses? I just think that if we truly are doing it for patient-centred care, we would be referring patients to the best suited healthcare professional. (GPN 6)

Having access to a specialist nurse was seen as particularly valuable in rural and remote regions where there may not be the same availability of services as in metropolitan areas.

… if you are in rural Western Australia, I may not have the ability to help you here, however, I can set up a Zoom meeting with an experienced nurse in the city who will step us through what needs to happen. (GPN 9)

Both study groups spoke strongly of the need for better integrated care between the GP and the GPN particularly following diagnosis. Involving the nurse as part of post-diagnostic care was perceived as essential. This approach was seen as an opportunity to start meeting the care recipient needs for early information, reassurance and support.

The GPNs stated that the short GP consultation time currently allocated was inadequate to support a person when disclosing the diagnosis and that the nurse could fill this gap.

… they’ve made a 10–15-minute appointment with the doctor and it’s not going to work. It’s just not going to work. But … say okay, I’m going to introduce you to the nurse, and she is going to talk to you today, she will organise the next upcoming appointments, what supports you need and the next investigations that we need to do and then I will see you on Friday when we’ll take the next step … (GPN 9)

One carer described the value of involving the GPN at the same time as the GP when disclosing the diagnosis as:

So when the doctor makes that appointment to say, right, I’m going to discuss this diagnosis with you, in their mind, the appointment, they should be making an appointment with the nurses as well … At a time when their life is cataclysmically changed, [the person living with dementia and the carer are] provided with no guidancance … I think that it would be fantastic if there was a nurse who could then take them from the doctor who’s just made the diagnosis, and says, come on, let’s do some discussion about this. Let’s find out what’s happening. What’s available? What can we do to make your life a little easier? … So, I think that the doctors and nurses perhaps need to find a way to work together as a team, rather than be seen as an adjunct. There should be no gap. The doctor should literally say, now the nurse is going to look after you throughout this whole journey. Then immediately, you would feel the shoulders drop with relief. (Carer 2)

Discussion

In this study, data collected from GPNs, people living with dementia and carers revealed three prospective models of care describing a nurse role in the provision of dementia care in the primary care setting. The models of care proposed are not discrete models. They have different focuses but share similar elements of care. Poorly defined primary care practitioner roles in dementia care are a barrier to diagnosis and management of dementia (Aminzadeh et al. 2012; Balsinha et al. 2022). These models provide a useful starting point for developing and evaluating frameworks of care delivery that describe potential roles of the GPN to better meet the care needs of people living with dementia and carers.

In the first proposed model, study participants described ‘a nurse-led model of dementia care’ in which the nurse was the primary contact and worked in partnership with the care recipients and other health providers to deliver best-practice person-centred dementia care. This care included on-going monitoring, information and support along the disease trajectory. This positioning of the GPN was in contrast to the traditional models of primary care in which the GP holds full responsibility for patient care (Johnson et al. 2024). The GPN study participants described nurse-led care as more than a task-orientated approach under the delegation of the GP. This is in accordance with Australian and International literature which describes nurse-led care with the nurse having the capacity to function independently, autonomously and interdependently with others (Johnson et al. 2024; Terry et al. 2024). Examples of effective models of nurse-led care in primary care settings can be found in chronic and age-related diseases (Chan et al. 2018) and frail aged care (Kasa et al. 2023). This potential nurse-led model of care is not limited to the clinic setting. In Australia, for example, the primary care funding model allows for GPNs to carry out annual health assessments for people aged 75 years and over in the community and chronic disease management care planning within residential aged care homes.

In the second model of care, GPNs acknowledged they are generalist primary care practitioners and that they may require support when care is outside their scope of practice or beyond their clinical expertise. This may particularly be the case in dementia care which has been well established as an area in which knowledge and skills are lacking both in nurses and GPs (Spenceley et al. 2015). Access to a specialist dementia nurse for advice and support was recognised as valuable by both the GPNs and care recipients participating in this study. A barrier to nurse-led models of care and autonomous decision-making is a lack of GP confidence in the nurse’s knowledge and skills (Aerts et al. 2020). Access to, and use of, nurse specialist support services may help mitigate this barrier.

The third model of care addresses the growing emphasis on post-diagnostic support within primary care (Prince et al. 2016). Post-diagnostic care in which nurses are central is recognised as a foundation of effective dementia management and enabling people and families to live as well as possible with dementia (Yamakawa et al. 2022). Both GPNs and care recipients in this study wanted better integrated care between the GP and the GPN particularly at the time of diagnosis. A nurse-enhanced model of post-diagnostic dementia care was described by study participants as one in which the GPN engaged with the care recipients immediately following the consultation with the GP in which diagnosis was discussed. The GPN would then provide information, support, care planning and monitoring. The effectiveness and sustainability of GP and GPN collaborative and complementary models of care are well established in chronic disease management (Halcomb et al. 2019). Post-diagnostic support delivered in primary care has a number of potential advantages including accessibility and the potential of a more holistic approach to meet the multiple complex health and social needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s) (Frost et al. 2020).

Despite the potential value of enhancing the GPN role in the care of people living with dementia and their carer(s) there is limited research on models of care for the GPN in dementia care delivery in Australian or International literature. The three models of dementia care provision by the GPN described in this study describe opportunities to better utilise the role of the GPN to meet the increasing demand for best-practice dementia care. Despite the potential of these nurse models of care in optimising the delivery of care in primary care, significant structural barriers exist to their implementation which would need to be addressed. These barriers include the primary care funding model, the general practice team hierarchy and limited collaboration with other health providers (McInnes et al. 2015; Gibson et al. 2024b). These findings can inform future research and influence the development, evaluation and scaling up of GPN models of care for people living with dementia and their carer(s) in primary care settings.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the use of semi-structured interviews to facilitate GPNs, people living with dementia and carers in contributing, exploring and clarifying their views on a research topic about which little is known. Another strength was the structured analysis process. The high level of agreement between the themes generated independently by the authors increased our confidence in the results.

A limitation was the small sample size; however, this is the nature of qualitative research, and all participants drew on their personal experiences, ensuring high internal validity, and there was considerable consistency in responses.

Conclusion

This study describes three models of dementia care delivery by the GPN from the perspectives of GPNs and people living with dementia and their carer(s). These findings can be used to guide the development, implementation and evaluation of models of care that support the integration of the provision of dementia care by GPNs within interdisciplinary primary care teams to better meet the healthcare needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s).

Data availability

The transcripts analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of funding

This research contributes to a larger program of work being conducted by the Australian Community of Practice in Research in Dementia (ACcORD), which is funded by a Dementia Research Team Grant (APP1095078) from the National Health and Medical Research Council. Caroline Gibson is supported by a University of Newcastle Postgraduate Research Scholarship from the Faculty of Health and Medicine.

Author contributions

CG conceived the study. CG, DG, DP, AH and MY contributed to the study design. CG drafted the manuscript. CG, DG and DP independently reviewed the transcripts and coded the data, and AH and MY assisted with resolving any discrepancies in the coding. DG, AH, MY and DP provided critical commentary on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version.

References

Aerts N, Van Bogaert P, Bastiaens H, Peremans L (2020) Integration of nurses in general practice: a thematic synthesis of the perspectives of general practitioners, practice nurses and patients living with chronic illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29, 251-264.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Aminzadeh F, Molnar FJ, Dalziel WB, Ayotte D (2012) A review of barriers and enablers to diagnosis and management of persons with dementia in primary care. Canadian Geriatrics Journal 15, 85-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Balsinha C, Iliffe S, Dias S, Freitas A, Barreiros FF, Gonçalves-Pereira M (2022) Dementia and primary care teams: obstacles to the implementation of Portugal’s Dementia Strategy. Primary Health Care Research and Development 23, e10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bamford C, Wilcock J, Brunskill G, Wheatley A, Harrison Dening K, Manthorpe J, Allan L, Banerjee S, Booi L, Griffiths S, Rait G, Walters K, Robinson L, on behalf of the PriDem study team (2023) Improving primary care based post-diagnostic support for people living with dementia and carers: developing a complex intervention using the theory of change. PLoS ONE 18, e0283818.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chan RJ, Marx W, Bradford N, Gordon L, Bonner A, Douglas C, Schmalkuche D, Yates P (2018) Clinical and economic outcomes of nurse-led services in the ambulatory care setting: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 81, 61-80.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Davidson P, Hickman L, Graham B, Phillips J, Halcomb E (2006) Beyond the rhetoric: what do we mean by a ‘model of care’? The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 23, 47-55.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dröes RM, Chattat R, Diaz A, Gove D, Graff M, Murphy K, Verbeek H, Vernooij-Dassen M, Clare L, Johannessen A, Roes M, Verhey F, Charras K, INTERDEM sOcial Health Taskforce (2017) Social health and dementia: a European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging & Mental Health 21, 4-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Eley DS, Patterson E, Young J, Fahey PP, Del Mar CB, Hegney DG, Synnott RL, Mahomed R, Baker PG, Scuffham PA (2013) Outcomes and opportunities: a nurse-led model of chronic disease management in Australian general practice. Australian Journal of Primary Health 19, 150-158.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, Kallmyer B (2018) The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. Gerontologist 58, S10-s19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Frost R, Rait G, Wheatley A, Wilcock J, Robinson L, Harrison Dening K, Allan L, Banerjee S, Manthorpe J, Walters K, PriDem Study project team (2020) What works in managing complex conditions in older people in primary and community care? A state-of-the-art review. Health & Social Care in the Community 28, 1915-1927.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ghorob A, Bodenheimer T (2015) Building teams in primary care: a practical guide. Families Systems & Health 33, 182-192.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson C, Goeman D, Hutchinson A, Yates M, Pond D (2021) The provision of dementia care in general practice: practice nurse perceptions of their role. BMC Family Practice 22, 110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gibson C, Goeman D, Pond CD, Yates M, Hutchinson AM (2024a) The perspectives of people living with dementia and their carers on the role of the general practice nurse in dementia care provision: a qualitative study. Australian Journal of Primary Health 30, PY24071.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson C, Goeman D, Pond D, Yates M, Hutchinson A (2024b) General practice nurse perceptions of barriers and facilitators to implementation of best-practice dementia care recommendations—a qualitative interview study. BMC Primary Care 25, 147.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Halcomb EJ, McInnes S, Patterson C, Moxham L (2019) Nurse-delivered interventions for mental health in primary care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Family Practice 36, 64-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Helmer-Smith M, Mihan A, Sethuram C, Moroz I, Crowe L, MacDonald T, Major J, Houghton D, Laplante J, Mastin D, Poole L, Wighton MB, Liddy C (2022) Identifying primary care models of dementia care that improve quality of life for people living with dementia and their care partners: an environmental scan. Canadian Journal on Aging 41, 550-564.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Johnson C, Ingraham MK, Stafford SR, Guilamo-Ramos V (2024) Adopting a nurse-led model of care to advance whole-person health and health equity within Medicaid. Nursing Outlook 72, 102191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kasa AS, Drury P, Traynor V, Lee S-C, Chang H-C (2023) The effectiveness of nurse-led interventions to manage frailty in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review. Systematic Reviews 12, 182.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mansfield E, Noble N, Sanson-Fisher R, Mazza D, Bryant J (2019) Primary care physicians’ perceived barriers to optimal dementia care: a systematic review. The Gerontologist 59, e697-e708.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McInnes S, Peters K, Bonney A, Halcomb E (2015) An integrative review of facilitators and barriers influencing collaboration and teamwork between general practitioners and nurses working in general practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 71, 1973-1985.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Minghella E, Schneider K (2012) Rethinking a framework for dementia 2: a new model of care. Working With Older People 16, 180-189.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Norful A, Martsolf G, de Jacq K, Poghosyan L (2017) Utilization of registered nurses in primary care teams: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 74, 15-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prince M, Comas-Herrera A, Knapp M, Guerchet M, Karagiannidou M (2016) Improving Healthcare For People Living With Dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International, London. Available at https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2016.pdf

Spenceley SM, Sedgwick N, Keenan J (2015) Dementia care in the context of primary care reform: an integrative review. Aging & Mental Health 19, 107-120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Supper I, Catala O, Lustman M, Chemla C, Bourgueil Y, Letrilliart L (2015) Interprofessional collaboration in primary health care: a review of facilitators and barriers perceived by involved actors. Journal of Public Health 37, 716-727.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Swanson M, Wong ST, Martin-Misener R, Browne AJ (2020) The role of registered nurses in primary care and public health collaboration: a scoping review. Nursing Open 7, 1197-1207.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Terry D, Hills D, Bradley C, Govan L (2024) Nurse-led clinics in primary health care: A scoping review of contemporary definitions, implementation enablers and barriers and their health impact. Journal of Clinical Nursing 33, 1724-1738.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19, 349-357.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Yamakawa M, Kanamori T, Fukahori H, Sakai I (2022) Sustainable nurse-led care for people with dementia including mild cognitive impairment and their family in an ambulatory care setting: a scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Practice 28, e13008.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |