Investigating men’s perspectives on preventive health care within general practice: a qualitative study

Ruth Mursa A B * , Gemma McErlean A B C , Christopher Patterson A B Elizabeth Halcomb A BA

B

C

Abstract

Chronic conditions are a major health concern. Most Australian men are overweight or obese and half live with at least one chronic health condition. Many chronic conditions are preventable and treatable by reducing lifestyle risk factors. General practice delivers a range of services, including preventive health care; however, men have been noted to have low engagement with general practice. This study aimed to investigate men’s perspectives on preventive health care within general practice.

Seventeen semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of Australian men recruited from the NSW Rural Fire Service following an initial survey. Interviews sought to explore men’s perspectives on engagement in preventive health care within general practice. Data were thematically analysed.

Two sub-themes were identified relating to men’s engagement in preventive health care within general practice. ‘The scope of general practice services’ highlighted diverse understandings among men’s perceptions of the role and value of preventive health care. Whereas ‘addressing lifestyle risk factors’ revealed the nature of communication and advice provided within general practice concerning lifestyle risks and behavioural change. The findings indicated that when advice is provided, men want tangible and meaningful healthcare strategies that support them in making behavioural changes.

General practice clinicians need to prioritise preventive health care. Proactively addressing preventive health care with men and supporting them to make informed decisions about their lifestyle choices has the potential to enhance their health and reduce chronic health conditions.

Keywords: chronic conditions, general practice, general practice nurses, general practitioners, lifestyle risk reduction, male, men, preventive health care.

Introduction

Chronic conditions are a significant health concern, resulting in reduced well-being, disability and early death (Australian Institute of Health Welfare 2024a). These conditions arise from a complex combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors (World Health Organization 2023). Indeed, in Australia, around 90% of all deaths are attributed to chronic conditions (Australian Institute of Health Welfare 2024a). Over 50% of men aged 45–64 years have at least one chronic condition, and for men aged over 65 years, this increases to 75% (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023).

Many chronic conditions are preventable, and the early identification of lifestyle and biomedical risk factors can facilitate intervention and risk reduction that can decrease morbidity and mortality (Sun et al. 2022). With approximately 75% of Australian males living with overweight/obesity, together with poor diet and physical inactivity, smoking and alcohol consumption, the risk of developing a chronic condition increases (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). To reduce the prevalence of chronic conditions, modifiable behavioural risk factors need to be addressed (World Health Organization 2023).

General practice is the access point to the healthcare system and seeks to provide ongoing health care across all life stages (Australian Institute of Health Welfare 2024b). General practice services are diverse and include the provision of acute health care, health screening and risk reduction, and management of chronic conditions (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). As the burden of chronic conditions rises, general practice is pivotal in health promotion and patient education, early intervention and support for self-management (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2022).

Although a number of health system and policy challenges exist (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2022), general practitioners (GPs) and general practice nurses (GPNs) work with patients to identify and address lifestyle risk factors and empower them to be more informed about the choices they make about their health (James et al. 2021; The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2024). Within a team-based approach, GPNs undertake a range of preventive healthcare activities including immunisations, health assessments, health screening and lifestyle risk modification (James et al. 2021; Morris et al. 2022). Preventive health care is crucial in promoting and maintaining the health and well-being of our community by reducing the risk of negative health conditions and promoting the early detection of health issues to facilitate the kind of prompt intervention that optimises outcomes (AbdulRaheem 2023). However, men are reportedly less engaged with general practice compared to women (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). This translates into missed opportunities for critical preventive health care that can reduce lifestyle risks, promote healthy behaviours and improve early detection (Harris and McKenzie 2006; Mursa et al. 2022). To seek to understand this issue from the consumer perspective, this paper reports on men’s perspectives on preventive health care within general practice. Understanding these issues will inform future strategies to promote men’s engagement with general practice.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative descriptive study was the second phase of a sequential mixed-method project. Initially, an online, cross-sectional survey sought to explore men’s health status, lifestyle risk, preventive healthcare engagement and health literacy. Given the large volume of data, survey data are reported separately (Mursa et al. 2024). In this second phase, semi-structured interviews were undertaken to explore men’s engagement with general practice.

Recruitment and sample

Adult male volunteers and staff from the New South Wales Rural Fire Service (NSW RFS) were recruited via a dedicated RFS Facebook page and within the organisation’s e-bulletin to undertake an online survey that explored men’s engagement with general practice. Men from the NSW RFS were recruited to provide a sample of men from rural and urban areas with diverse socio-economic and educational backgrounds. Survey respondents were asked to provide contact details if they were interested in participating in a subsequent interview.

Of the 441 survey respondents, 216 (48.98%) respondents indicated a willingness to be interviewed. A purposeful sampling method was used to select interview participants from this group. To provide maximum variation in age, geographic location and engagement with general practice, potential participants were stratified based on survey demographics and then individuals were selected from each stratum. Contact with potential participants occurred via email, whereby study information was provided and any questions answered. If the person was willing to participate, they were provided a link to an electronic consent form and a mutually agreeable interview time was arranged. Participants were recruited until no new information was forthcoming (Braun and Clarke 2022).

Data collection

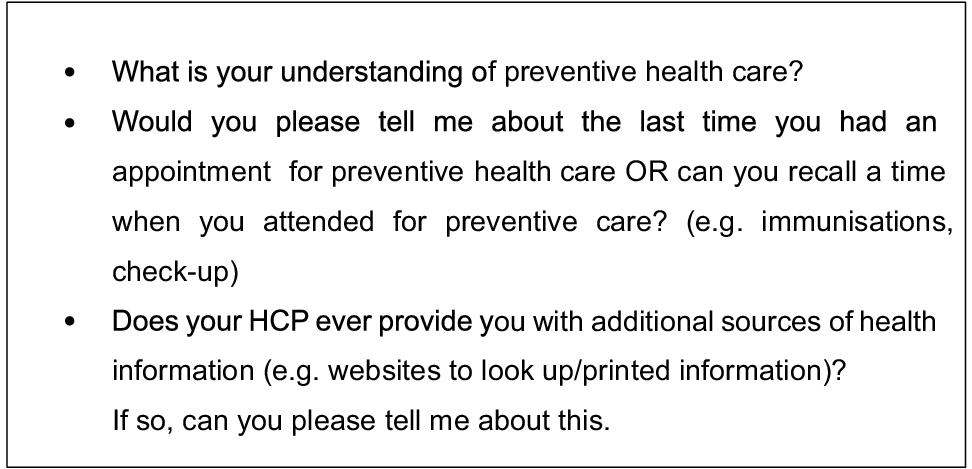

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (RM) between May and July 2023. The interviewer is a PhD candidate and a nurse practitioner with extensive clinical experience in primary care. Due to participants’ geographical dispersion, interviews were offered via videoconference or telephone. All participants chose videoconferencing. Interviews followed an interview guide that was developed drawing on a review of the literature and the survey data (Mursa et al. 2022, 2024) (Fig. 1). Probes and prompts were used to further explore responses. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company. Field notes documented the interviewers’ observations and thoughts during and after the interviews.

Data analysis

All transcripts were checked against the audio recordings and de-identified before being uploaded into NVivo Version 12 (Lumivero 2023) for analysis. Inductive thematic analysis, informed by Braun and Clarke (2022), was used to analyse the data. Data familiarisation occurred as transcripts were read and re-read and audio-recorded interviews were listened to. Initial codes were generated and labelled, organising data items into meaningful groups. Themes and sub-themes were identified from the data. The research team, comprising the nurse practitioner/doctoral candidate (RM) and three nurse academics (GM, CP and EH) with extensive qualitative research and primary care experience, agreed on the reviewed, defined, refined and verified themes. Selected extracts from the data were included in the narrative.

Ethical issues

The NSW RFS gave permission to undertake the study and it was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Wollongong (Approval no 2022/225). Participation in the study was voluntary with written consent obtained prior to each interview. Pseudonyms were used to protect participants’ confidentiality.

Results

Participant characteristics

Seventeen interviews were conducted before data saturation was achieved. The mean age of participants was 52.6 years (range 21–76 years) (Table 1). Eight participants (47%) resided in a rural location.

Thematic structure

The role of the general practice in preventive health care had two sub-themes, namely: (a) the scope of general practice services; and (b) addressing lifestyle risk factors.

Perceptions regarding the role of general practice in preventive health care varied among participants. Bekim identified that ‘preventive health care is about seeing your GP, but also about lifestyle.’ Several other participants identified that general practice was a key place for preventive health care, including health screening, check-ups and counselling to prevent health problems, whereas Mark ‘insists on having an annual check-up’ and Cade identified that general practice provided regular ‘STI checks’ and ongoing mental health care ‘to stop depression and speak to someone sooner before it happens’. Likewise, Ellis acknowledged that ‘due to my complexion, I like going in for regular skin checks’ and Hassan shared ‘when I go to the doctors next, I’m going to mention my family history of prostate cancer…. I want to get tested.’

However, there was some lack of clarity around what could be managed in general practice versus specialty services. For example, Parker described general practice as providing care for ‘GP-related issues’ but said he would ‘go to the skin clinic if I’ve got skin-related stuff’. Indeed, Nate described general practice as a place to go ‘when there’s something wrong with my health,’ as did Dan, who saw general practice as a place that ‘treats, rather than going into prevention and what you should do about lifestyle.’ This highlights a lack of knowledge about the scope of preventive care available within general practice.

Some participants could not see the need or benefit of having a ‘check-up’ or engaging with preventive health care. Indeed, despite being encouraged by his GP to attend routinely, Gabe acknowledged that ‘I don’t go for a check-up.’ Additionally, Floyd, who described himself as ‘healthy’, viewed having an appointment for a check-up as ‘wasting the doctor’s time.’ There was also a degree of complacency about preventive health noted among some participants.

I just don’t see the benefit in it. I know I should … somewhere I’ve got my little government pack (bowel screen) that I must do, but anyway who cares, I’ll get round to it. (Floyd)

Some participants acknowledged that ‘lifestyle choices and my activity level directly impact my health’ (Alex), whereas others spoke of their conscious attempts to improve their health through self-directed efforts to stay active.

I just keep moving and do a reasonable amount of exercise. (Joel)

I set myself a goal to make a change and get my cholesterol down through lifestyle. (Gabe)

A few participants spoke of their GP actively addressing lifestyle risk factors during consultations. Hassan described how his GP routinely asks, ‘How many alcoholic drinks do I have in a week?’ whereas Mark recounts being asked ‘Do you smoke? Do you drink?’.

However, several other participants described how their GPs had never discussed lifestyle risk factors or how to reduce lifestyle risks with them.

No, no, no aspect of my lifestyle ever came up. I said exercise came up maybe 2 or 3 times in those 20 years. Alcohol consumption, never. Diet, never. I can’t remember the last time he ever asked me about weight. (Bekim)

Generally it’s very much about treat the symptoms, not the cause, I don’t think I’ve ever had a GP ask me about my diet. (Ellis)

Additionally, the opportunistic lack of addressing lifestyle risks and healthy living advice during a consultation was noted by some participants.

…it was very much, whatever you were there for it was that, and then out! … it was very much a tick box exercise. (Luis)

When the GP offered lifestyle change advice, participants described receiving limited practical advice about strategies to achieve behavioural change. Indeed, participants expected to receive more comprehensive and explicit advice that went beyond a single instruction or a flippant directive. For example, Luis commented that the GP advised him to ‘lose weight’, and Alex recounted ‘he told me I need to move, and I need to get the weight off.’ However, neither participant received a referral to additional services or advice about strategies to assist in weight loss. Beyond discussions about weight, other participants recalled:

One time, one of my cholesterol numbers went up and she said, that’s come up a bit, you better watch your lifestyle, but she didn’t say cut down on alcohol or anything else. (Dan)

They just told me I had to give them up [cigarettes]. Didn’t provide anything at all or any prescription medication. No, nothing, he just turned around and said, you must do this. (Nate)

Despite attending what they described as a dedicated appointment with the GP for preventive healthcare screening and education, Floyd recalled that practical lifestyle advice was still not forthcoming:

When I had my 45-year-old check, doc was like, your cholesterol’s a little bit way too high, you need to get that down. He (GP) provided nothing, no detailed information, or maps to follow, or anything like that.

Discussion

The study examined men’s perspectives on preventive health care within general practice. Findings demonstrated a varied understanding of the role of prevention and the experience of receiving preventive care. Having a greater appreciation of men’s perceptions of the diverse roles of general practice can assist in targeting health promotion programs to encourage men’s engagement in preventive health care. Our study indicates that there is significant potential to enhance the communication of lifestyle risks, support behavioural changes and reduce the impact of chronic conditions on men by a combination of enhancing the quality of preventive care delivery and raising awareness of these services among men within the community.

This study found that many participants did not comprehend the diversity of health care that can be provided within general practice beyond acute services. Participants saw the role of general practice as ‘repairing’ health rather than promoting health and preventing health deterioration. Similar findings are demonstrated within the literature, whereby men perceive general practice as a facility for addressing illness without fully recognising its role in preventive care (Ashley et al. 2020; Mursa et al. 2022). A study exploring men’s health service use across four social generations found that overall, some 39.2% of males attended general practice for preventive health care (McGraw et al. 2021). The failure to engage with preventive care identifies men’s lack of awareness of the scope of care provided within general practice, negatively impacting their help-seeking and engagement (Barbosa et al. 2018). Our findings identify an urgent need to promote general practice as a source of preventive health care to enhance engagement and improve health outcomes.

The findings identified the differences among participants’ perceptions in the value of preventive health care, with some participants perplexed as to its necessity. The individual’s perception of being ‘quite healthy’ has been shown to reduce the uptake of preventive health care, viewing it as a waste of time, money and resources (Chien et al. 2020). Furthermore, a recent Australian study by Smith et al. (2023) reported that more than half of men did not appreciate the importance of preventive health care such as screening and health checks, with younger men less likely to rate its importance compared with older men. When men have an ongoing relationship with a regular GP/general practice (Mursa et al. 2024) or even attendance at a practice (Ares-Blanco et al. 2024), the uptake of preventive care and screening activities is high, highlighting the importance of this relationship. The value of preventive health care is unquestionable in reducing lifestyle risk and the prevalence of preventable conditions (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021). However, we need to promote the importance of men’s access across the life course by building healthcare capacity and establishing systems that facilitate men’s engagement with general practice for preventive care.

Despite the potential benefits, this study identified that participants felt there was often poor communication by GPs about lifestyle risk reduction and few actionable strategies were provided. Although the reasons for this are likely multifactorial and involve a combination of health system factors and individual health provider issues (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021, 2022), this highlights a significant opportunity for change. The finding that few patients are provided with lifestyle advice by their GP has been previously reported (Henry et al. 2022; Albarqouni et al. 2024). For example, in a recent study, just 9% of respondents with insufficient fruit and vegetable intake were advised to increase their daily intake by their GP (Albarqouni et al. 2024). Ashley et al. (2020) similarly reported a lack of opportunistic health education provided within general practice to support behavioural change, contributing to consumers’ lack of understanding of the role of general practice in health promotion. Although the provision of advice alone does not equate to sustained behaviour change, Albarqouni et al. (2024) found that, when advice was provided, behavioural changes were more likely to occur. As participants in this study sought greater communication with their GPs about these issues and actionable strategies to help them reduce risk, this indicates a willingness from a consumer perspective to receive such input as part of routine care. Further research is needed to identify the macro, meso and micro level factors impacting such communication and inform strategies to address key barriers. Additionally, research can be used to identify those interventions that are most impactful in guiding this group to achieve sustained behaviour change.

When lifestyle advice is provided, simply recommending patients to ‘lose weight’ or ‘’stop smoking’ does not adequately encourage and support behavioural change (Mazza et al. 2011; Ashley et al. 2020). Addressing lifestyle risk and behavioural change is challenging (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021). However, the relational aspect of general practice provides a sound platform to address such issues in a person-centred manner (James et al. 2019; Keyworth et al. 2020). The use of motivational interviewing to enable shared decision-making is advantageous in supporting behavioural changes and beneficial in optimising healthcare interventions (Bischof et al. 2021). Communicating clear advice and practical strategies that support behavioural change requires intentional and meaningful conversations and information sharing (Keyworth et al. 2019). Using team-based care models and harnessing the multidisciplinary team’s expertise to the full scope of practice strengthens the communication and delivery of lifestyle advice within general practice (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021; James et al. 2021). Sharing the delivery of care across the multidisciplinary team can also help address the challenges of time and resource constraints (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2022).

The Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) acknowledges that our health system has a strong focus on treating people who are unwell rather than a focus on prevention. However, strategies that focus on keeping people well and support behavioural changes through coordinated action to reduce the risks of poor health and well-being are now a key focal point (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021). The increasing focus will also see an increase in the ongoing financial investment in preventive health to ensure a more equitable balance between treatment and preventive health care (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021, 2022). Moreover, partnering with consumers is vital in shifting the healthcare focus towards preventive care that promotes health and prevents illness. The voice of consumers and consumer groups in the delivery of preventive health care ensures sustainable and person-centred health partnerships (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

Limitations

Our findings are subject to limitations. Participants were recruited from a single organisation; men from other organisations may have had different perceptions. However, including men from diverse backgrounds, varied ages and locations across rural and urban NSW is a key strength of the study. The interviews were conducted via videoconferencing, which, although it has limitations, has strengths in that we could interview men from broad geographical locations and interview participants at a place and time that was mutually convenient to all involved. This study only gained the perceptions of men and did not collect data from health professionals. As such, data were limited to self-report and it was not possible to make inferences or draw conclusions about the behaviour or actions of health professionals and the factors that impacted their practice. Additionally, the recollections of the men may differ from those of the health professionals who provided the consultations.

Implications for policy and practice

The devastating and ever-increasing impact of chronic health conditions has significant social and financial consequences for individuals, families and the community. Study findings provide important insights for general practice providers to enhance community awareness and understanding of their role in the provision of preventive health care. Indeed, there is a crucial need for general practice providers to promote a greater focus on the value and importance of preventive health care in supporting overall health and well-being. Partnering with healthcare consumers to openly discuss lifestyle risk factors, both opportunistically and during routine consultations, is crucial. This collaboration, supported by the general practice team, enables patients to make positive lifestyle changes, addressing the burgeoning burden of disease.

Conclusion

Our study identified men’s varied perceptions of general practice’s role in providing preventive health care. The study has highlighted a perceived lack of communication regarding lifestyle risk within general practice. It has also identified insufficient actionable advice for men to support behavioural change. The study demonstrates that more needs to be done at national and local levels, to increase awareness of services provided within general practice by GPs, nurses and allied health. Concurrently, the general practice workforce requires ongoing educational support and infrastructure changes to enable skilled health professionals to have the time and resources to address lifestyle risks effectively. Building capacity in general practice for delivering effective preventive health care tackles the blight of chronic conditions and supports the health and well-being of men.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Declaration of funding

Ruth Mursa was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award from the University of Wollongong. Our research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

RM: conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, writing, review and editing. CP, GM, EH: supervision, conceptualisation, methodology, writing, review and editing.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the NSW RFS for their support in undertaking this project. The authors would also like to thank the men who took the time to participate in the interviews and who were so generous in their responses.

References

AbdulRaheem Y (2023) Unveiling the significance and challenges of integrating prevention levels in healthcare practice. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 14, 21501319231186500.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Albarqouni L, Greenwood H, Dowsett C, Glasziou PP (2024) Lifestyle advice from general practitioners and changes in health-related behaviour in Australia: secondary analysis of 2020–21 National Health Survey data. Medical Journal of Australia 220, 480-481.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ares-Blanco S, López-Rodríguez JA, Polentinos-Castro E, del Cura-González I (2024) Effect of GP visits in the compliance of preventive services: a cross-sectional study in Europe. BMC Family Practice 25, 165.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ashley C, Halcomb E, McInnes S, Robinson K, Lucas E, Harvey S, Remm S (2020) Middle-aged Australians’ perceptions of support to reduce lifestyle risk factors: a qualitative study. Australian Journal of Primary Health 26, 313.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/12/national-preventive-health-strategy-2021-2030_1.pdf

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2022) Australia’s Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan 2022–2032. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australias-primary-health-care-10-year-plan-2022-2032?language=en

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) The health of Australia’s males. AIHW, Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/men-women/male-health.

Australian Institute of Health Welfare (2024a) Chronic conditions. AIHW, Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/chronic-conditions

Australian Institute of Health Welfare (2024b) General practice, allied health and other primary care services. AIHW, Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/general-practice-allied-health-primary-care

Barbosa YO, Menezes LPL, de Jesus Santos JM, Cunha JO, de Menezes AF, Araújo DC, Albuquerque TIP, Santos AD (2018) Access of men to primary care services. Journal of Nursing UFPE/Revista de Enfermagem UFPE 12, 2897-2905.

| Google Scholar |

Bischof G, Bischof A, Rumpf HJ (2021) Motivational interviewing: an evidence-based approach for use in medical practice. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 118, 109-115.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chien SY, Chuang MC, Chen IP (2020) Why people do not attend health screenings: factors that influence willingness to participate in health screenings for chronic diseases. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 3495.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris MF, McKenzie S (2006) Men’s health: what’s a GP to do? Medical Journal of Australia 185, 440-444.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Henry JA, Jebb SA, Aveyard P, Garriga C, Hippisley-Cox J, Piernas C (2022) Lifestyle advice for hypertension or diabetes: trend analysis from 2002 to 2017 in England. British Journal of General Practice 72, E269-E275.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

James S, Halcomb E, Desborough J, McInnes S (2019) Lifestyle risk communication by general practice nurses: an integrative literature review. Collegian 26, 183-193.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

James S, Halcomb E, Desborough J, McInnes S (2021) Barriers and facilitators to lifestyle risk communication by Australian general practice nurses. Australian Journal of Primary Health 27, 30-35.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Keyworth C, Epton T, Goldthorpe J, Calam R, Armitage CJ (2019) ‘It’s difficult, I think it’s complicated’: health care professionals’ barriers and enablers to providing opportunistic behaviour change interventions during routine medical consultations. British Journal of Health Psychology 24, 571-592.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Keyworth C, Epton T, Goldthorpe J, Calam R, Armitage CJ (2020) Perceptions of receiving behaviour change interventions from GPs during routine consultations: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 15, e0233399.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mazza D, Shand LK, Warren N, Keleher H, Browning CJ, Bruce EJ (2011) General practice and preventive health care: a view through the eyes of community members. Medical Journal of Australia 195, 180-183.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McGraw J, White KM, Russell-Bennett R (2021) Masculinity and men’s health service use across four social generations: findings from Australia’s ten to men study. SSM - Population Health 15, 100838.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Morris M, Halcomb E, Mansourian Y, Bernoth M (2022) Understanding how general practice nurses support adult lifestyle risk reduction: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 78, 3517-3530.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mursa R, Patterson C, Halcomb E (2022) Men’s help-seeking and engagement with general practice: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 78 1938-1953.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mursa R, McErlean G, Patterson C, Halcomb E (2024) Understanding the lifestyle risk profile of men and their engagement with preventive care: a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith B, Moss TJ, Marshall B, Halim N, Palmer R, von Saldern S (2023) Engaging Australian men in disease prevention – priorities and opportunities from a national survey. Public Health Research and Practice 34(2), 33342310.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sun Q, Yu D, Fan J, Yu C, Guo Y, Pei P, Yang L, Chen Y, Du H, Yang X, Sansome S, Wang Y, Zhao W, Chen J, Chen Z, Zhao L, Lv J, Li L, China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group (2022) Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy at age 30 years in the Chinese population: an observational study. The Lancet Public Health 7, e994-e1004.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

World Health Organization (2023) Noncommunicable diseases. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases