The role of general practice to address the supportive care needs of Australian cancer survivors: a qualitative study

Olivia Bellas A , Emma Kemp

A , Emma Kemp  A , Jackie Roseleur

A , Jackie Roseleur  A * , Laura C. Edney

A * , Laura C. Edney  A , Candice Oster

A , Candice Oster  B Jonathan Karnon

B Jonathan Karnon  A

A

A

B

Abstract

Cancer survivors have a broad range of supportive care needs that are not consistently managed in general practice. Understanding the barriers primary healthcare providers face in providing high quality supportive care is crucial for improving the delivery of supportive care in general practice.

This Australian qualitative study involved semi-structured interviews with general practitioners (n = 9), practice nurses (n = 8), and a community liaison worker employed in general practice (n = 1), to explore barriers and facilitators to identifying and managing supportive care for cancer survivors. Data were thematically analysed to develop recurring themes related to the identification and provision of supportive care.

Four major themes were developed: identification of supportive care needs, time and provision of supportive care, challenges in supportive care for diverse populations, and desire for more information. Improved education; enhanced communication across all levels of healthcare, including centralised access to patient information; and greater knowledge of available services were highlighted as facilitators to the management of supportive care for cancer survivors.

Targeted efforts to support the facilitators identified here can contribute to more effective management of supportive care for diverse cancer survivor populations to improve the overall quality of care and health outcomes for these individuals.

Keywords: cancer services, cancer survivorship, general practice, general practitioners, healthcare system, oncology, practice nurses, unmet needs.

Introduction

Cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, with an estimated 162,000 new cancer diagnoses made in Australia in 2022 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022). While the average survival has improved over time for many cancers, the non-fatal health burden of cancer remains higher than all other disease groups (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022). Individuals living with and beyond cancer often have supportive care needs including physical, psychosocial, and practical needs that vary by cancer type, stage in the cancer trajectory, and individual differences (Fitch 2008). These supportive care needs can range from complex medical issues such as malnutrition that may require specialised care (Kaegi-Braun et al. 2021), through to more routine management of psychosocial care that can be addressed in general practice (Jefford et al. 2020). Current evidence suggests that there is a high degree of unmet supportive care needs among cancer survivors in Australia (Roseleur et al. 2023). The impact of these unmet needs on mental health (e.g. Bellas et al. 2022) and survival gains (Basch et al. 2017) is substantial.

In Australia, general practice is focused on the delivery of preventative care, early intervention, and chronic disease management by general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses (PNs) (Gordon et al. 2022). The role of general practice in cancer care has typically focused on prevention and early detection. However, many cancer survivors support the involvement of GPs and PNs in their follow-up care (Meiklejohn et al. 2016; Young et al. 2016), and GPs have been specifically identified as the preferred healthcare provider for managing cancer survivors’ psychosocial needs (Deckx et al. 2021).

Despite the potential for cancer survivors’ supportive care needs to be treated in general practice, this is not part of routine practice (Jefford et al. 2022). Models of survivorship care involving primary care have been proposed (Emery et al. 2017) but these have not been widely implemented in practice (Jefford et al. 2022). A recent Australian qualitative study explored the perspectives of GPs, PNs, and practice managers on the delivery of cancer survivorship care, reporting large variation in perceptions of the needs of cancer survivors (Fox et al. 2022). Fox et al. (2022) provided important recommendations for consensus guidelines clarifying cancer survivors’ needs in general practice, supporting clear role delineation, and providing education to support different roles to understand patient care needs. However, less is known about the barriers and facilitators to managing supportive care needs as a specific component of survivorship care within general practice in Australia. We sought to explore the identification of supportive care needs in Australian general practice and explore current approaches, barriers, and facilitators to their routine management.

Methods

Design and study setting

This interview study used a Codebook Thematic Analysis approach (Braun and Clarke 2022) to understand how supportive care needs are currently identified and managed in Australian general practice, using a coding frame of ‘barriers and facilitators’ to explore and summarise the data. Data were collected from interviews with GPs, PNs, and a community liaison worker, who were employed across major cities of New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia and inner and outer regional areas of South Australia. This study has been reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (O’Brien et al. 2014) (Supplementary material).

Participant recruitment

Participants were recruited through email invitations to professional networks, recruitment flyers on a social media group for PNs, and through directly approaching practices via telephone and email. Initial recruitment targeted GPs and PNs at any location; however, as the study progressed, participants were purposively sought from diverse areas to elicit a broader range of perspectives, particularly from practices in more socio-economically disadvantaged and regional areas. Participants received a A$100 gift voucher as an honorarium for their time and contribution. Sample size was guided by the Information Power Model proposed by Malterud et al. (2016), which states sample size should be determined by contribution of new knowledge from the analysis (rather than by ‘saturation’). Therefore, the more information the sample holds relevant to study aims, the lower the number of participants required, with adequacy of the sample evaluated continuously during the research process. The decision to stop recruitment was determined based on this model, once the research team deemed the sample size appropriate with reference to the study’s narrow objectives, dense sample specificity (GPs and PNs in general practice), representation of general practices in socio-economically disadvantaged and regional areas, and strong dialogue between interviewers OB/LE and participants. Coding of the final interviews only provided information that supported the existing developing themes, with no new codes or themes identified (and so could be considered to have reached ‘saturation’), however, the themes provided an informative picture of the barriers and facilitators experienced in managing supportive care needs in primary care; therefore, the sample size was deemed sufficient for a comprehensive analysis and the decision to stop recruiting was made on this basis.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview guide was developed (Table 1) that included a brief introduction about the interviewers’ background and the purpose of the study. Seventeen interviews were conducted via telephone and one via online video conferencing between July 2020 and September 2021. Each interview was recorded through audio recording (n = 14) or notetaking (n = 4), based on participant preferences, and ranged from 11 to 45 min (mean = 25.4). The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and read simultaneously with audio to ensure the accuracy of the data. The interviews recorded with notetaking were expanded on immediately after each interview to ensure accuracy and to include any additional observations. These were then analysed alongside transcribed recordings. Data were stored on a secure password-protected server. The interviewers (OB, LE) had non-clinical academic backgrounds in public health (OB) and psychology (LE). OB also had experience working in a tertiary healthcare centre, therefore their experience may have influenced discussion related to the interplay between general practice and tertiary care. Neither interviewer nor any other member of the research team had experience working in primary care. All members of the research team committed to reflexive practices to remain aware of and mitigate the influences of their backgrounds and personal experiences throughout the research process.

| Section | Interview guide | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Backgound | Demographic characteristics/professional background of participant/practice details What type of patients do you usually see? What is the average number of cancer patients you see in a week? | |

| 2. Understanding of supportive care needs | What do you believe to be SCNs? What is your understanding of supportive cancer care? What specific types of SCNs do you think cancer patients have? | |

| 3. Identification of supportive care needs | Do you identify SCNs in your cancer patients? If so, how, and how often? Do you feel comfortable discussing all possible SCNs with patients? Do your patients often identify their own SCNs with you? What priority is placed on discussing SCNs? Do you receive any information from tertiary care on your patients’ SCNs? | |

| 4. Management of supportive care needs | What do you think is the most important SCN to manage? Do you feel you have enough time to identify and manage SCNs? Are there any SCNs you feel you cannot manage within your practice? Do you think SCNs are better managed by different HCPs? Do you consult with other HCPs regarding SCNs for patients? Do you use General Practice Management Plans for your cancer patients? | |

| 5. Barriers/facilitators | What do you believe are the barriers and facilitators to identifying and managing SCNs in general practice? How do you think the processes for identifying and managing SCNs could be improved? |

HCPs, healthcare professionals; SCNs, supportive care needs.

Data analysis

An inductive thematic analysis using a pragmatic approach was adopted for the study, following Braun and Clarke (2006). Authors OB and LE conducted the interviews, OB transcribed the interviews, OB coded all interviews and three interview transcripts independently coded by EK and JR for comparison. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Consolidation of initial codes into themes, as well as generating, reviewing, and refining themes were achieved iteratively through critical discussion at regular team meetings (OB, EK, and JR). NVivo (Release 1.3) was used to manage, code, and collate data.

Results

The total sample included GPs (n = 9), PNs (n = 8), and a community liaison worker (n = 1). The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

| Characteristic | PNsA (n = 9) | GPs (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 100 | 67 | |

| Time in profession (years; mean (s.d.)) | 21.3 (12.4) | 20.2 (8.5) | |

| Time in primary care role (years; mean (s.d.)) | 9.6 (7.7) | 13.5 (10.5) | |

| Geographical region (%) | |||

| Major city | 66.7 | 111.1 | |

| Inner regional | 22.2 | 0 | |

| Outer regional | 11.1 | 0 | |

| IRSAD (%) | |||

| 1 (most disadvantaged) | 44.4 | 11.1 | |

| 2 | 22.2 | 44.4 | |

| 3 | 22.2 | 22.2 | |

| 4 | 11.1 | 0 | |

| 5 (most advantaged) | 11.1 | 33.3 | |

| Type of practice (billing)B (%) | |||

| Bulk | 22.2 | 0 | |

| Mixed | 88.9 | 66.7 | |

| Private | 11.1 | 44.4 | |

Note. Total aggregations are greater than participants for IRSAD and Type of Practice demographics in the PN group as two participants worked in more than one practice.

GP, general practitioner; PN, practice nurse; IRSAD, Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (1 = most disadvantaged to 5 = most advantaged).

| Participant ID | Time in profession (years) | Time in primary care role (years) | State | Geographical region | IRSAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN1 | 18 | 9 | SA | Outer-metropolitan | 1 | |

| PN2 | 34 | 26 | SA | Outer-metropolitan | 3 | |

| PN3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | SA | Metropolitan | 4, 5A | |

| PN4 | 8 | 7 | SA | Rural | 2 | |

| PN5 | 31 | 15 | SA | Outer-metropolitan | 1, 3A | |

| PN6 | 40 | 14 | SA | Outer-metropolitan | 1 | |

| PN7 | 20 | 2.5 | SA | Outer-metropolitan | 3 | |

| PN8 | 24 | 5 | SA | Major city | 1 | |

| CommunityLiaison PN | 15 | 6.5 | SA | Major city | 1 | |

| GP1 | 33 | 28 | SA | Metropolitan | 2 | |

| GP2 | 9 | 4 | SA | Metropolitan | 3 | |

| GP3 | 20 | 15 | SA | Metropolitan | 2 | |

| GP4 | 21 | 5 | NSW | Metropolitan | 5 | |

| GP5 | 8 | 2.5 | VIC | Metropolitan | 5 | |

| GP6 | 19 | 9 | NSW | Metropolitan | 5 | |

| GP7 | 20 | 16 | SA | Major city | 2 | |

| GP8 | 20 | 10 | SA | Major city | 3 | |

| GP9 | 32 | 32 | SA | Major city | 1, 2A |

Key findings

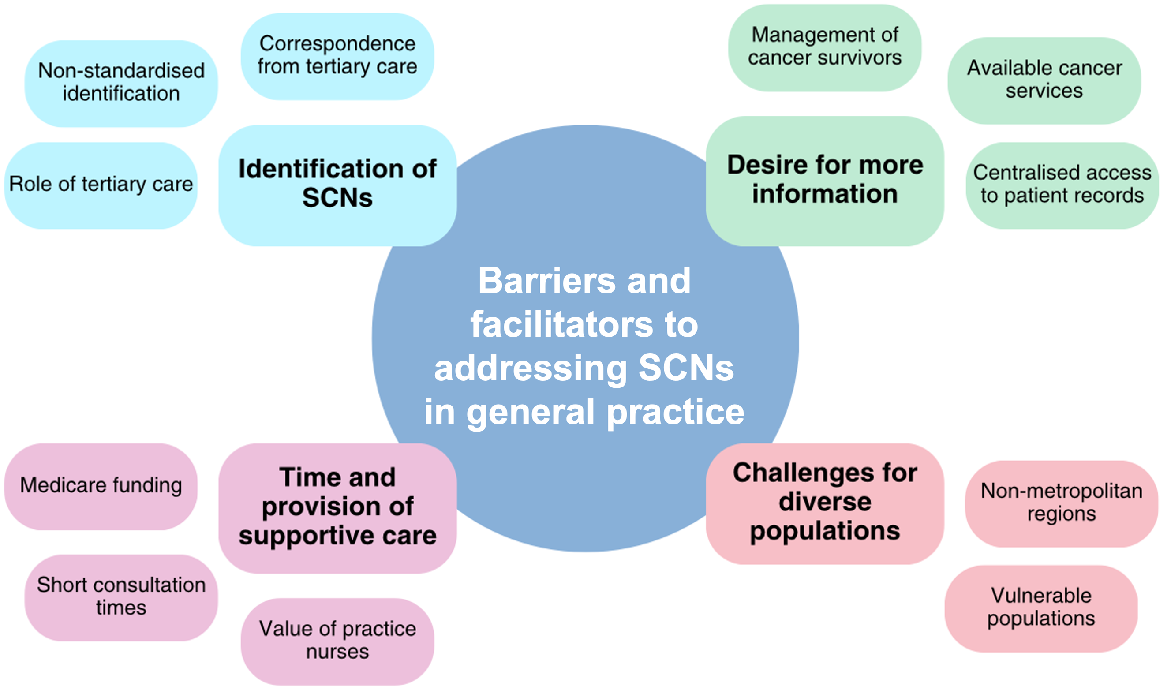

Four themes were developed reflecting the barriers and facilitators to identifying and managing supportive care needs of cancer survivors in general practice. Fig. 1 summarises each theme with its respective sub-themes.

Summary network of themes relating to the barriers and facilitators to addressing supportive care needs in primary care. SCNs, supportive care needs.

There was an overall lack of clarity about who should identify supportive care needs, which was explored in three subthemes: (1) non-standardised identification, (2) correspondence from tertiary care, and (3) role of tertiary care.

The identification of supportive care needs appeared to be a non-standardised process across practices, although common approaches to identifying needs were noted. Most participants described that they identify the supportive care needs of their patients through informal discussion, for example:

… first, I just ask them, you know, how they’re coping, how they’re feeling … (GP6)

I think I always go in with, let me check how you’re doing and then we’ll talk about the physical aspects of your cancer care. (PN7)

The follow-up questions GPs and PNs would ask to understand supportive care needs varied depending on their practice, professional background, and experience with cancer survivors. One GP acknowledged how a ‘… GPs’ personal experience with cancer, their medical experience with cancer, their current awareness of the field’ (GP6) influenced their consideration of supportive care needs. A lack of standardisation in addressing supportive care needs was highlighted – ‘… there is a bit of lack of guidance and lack of standardisation’ (GP6). Further illustrating this lack of standardisation, some PNs had a very proactive approach to identifying supportive care needs:

Today I just knocked on the door of the doctor and asked if I could visit and come into the consult and just ask … what are you doing about food? What are you drinking? … just assessing in my mind, is he getting enough calories and fluids and things like that. Do we need to intervene? (PN6)

In contrast, another PN felt that the dynamic of the practice they worked in hindered their ability to identify supportive care needs:

… we don’t get that communication [from within the practice], basically unless they [patients] tell us … it would just be nice to be armed, to be ready to say … I’m very sorry I didn’t know this was happening, is your husband, ok? And how are your children feeling? You know, just sort of to be, yeah, more involved basically. (PN2)

Some had their own approaches to identify supportive care needs such as:

… a set of electronic questions to ask patients. Some questions are generic and then some are tailored to the specific disease. For cancer we ask about mental health, diet and nutrition, exercise, pain, and mobility. (PN8)

Others were more dependent on patients identifying and reporting issues:

Sometimes I probably identify it, if they haven’t, like if they’re not coming in to ask anything in particular, there may be something that, you know, I’ve suggested and put in place. (PN1)

I probably wouldn’t say we identify them. I would say that the patient identifies them, and we make ourselves available … (PN4)

Correspondence from tertiary care can also be used to identify supportive care needs. However, most participants did not routinely receive correspondence from tertiary care about patients’ supportive care needs. Any correspondence received from hospitals appeared to be mostly clinically related, as outlined by two GPs:

… the hospitals very much tend to focus on the clinical side of things, not the peripheral support needs. (GP1)

The average discharge summary probably won’t have that kind of information. It may have reference to the fact that they’re being seen. That they’re going to have community physio or something. But it won’t necessarily identify that, you know, this individual’s specific supportive care needs. (GP5)

Even appropriate clinical correspondence from tertiary care was believed to be difficult to obtain ‘let alone any supportive care [correspondence]’ (PN5).

In contrast, one GP felt they did receive adequate supportive care needs correspondence from tertiary care:

So, the discharge letters are quite comprehensive and also, I receive from the nurses about what they have already done and what is expected from me, so this is acceptable, and this is good communication. (GP2)

Several participants believed there is a place to identify and screen supportive care needs in tertiary care. One PN (who is also a cancer survivor) described the lack of consideration of supportive care needs in tertiary care with her anecdote as a patient:

I think supportive care is pretty much left up to whoever is looking after them in the community … They were absolutely brilliant at what they do [cancer service] but there was no discussion about any other supportive needs which somebody may have wanted. (PN5)

Screening for supportive care needs in tertiary care appeared to be welcomed by GPs, ‘…it would be good if it was maybe screened for in hospital and then just a brief flagging summary to us …’ (GP5) as a potential facilitator for alleviating GP workload and improving management of supportive care needs in primary care, ‘I think it needs to be done in the hospital … so, you know, we’re not fooling around in a GP surgery trying to sort things out last minute’ (GP1).

In contrast, one GP considered that with clear role definitions there is capacity for supportive care needs to be both identified and managed in general practice:

… if GPs are made aware that this is one of their roles in cancer management, cancer survivorship, then they don’t really need or expect to have something from the tertiary centre … I don’t think a lot of GPs are clear on what is actually happening in the tertiary centre, sometimes they might assume that it’s all been attended to … (GP6)

Inadequate time due to short consultations and GP funding mechanisms were identified as barriers to managing supportive care needs, with better use of PN time recognised as a facilitator to managing supportive care needs in primary care.

Participants discussed the time-consuming nature of addressing supportive care as a barrier to its appropriate provision within time-constrained general practice consultations:

These types of consultations take quite a lot of time, you end up running very late in your wait room, which creates quite an issue. (GP6)

This was particularly pertinent for the psychological needs of cancer survivors:

Dealing with psychological distress takes a lot of time, you can’t just, you know, write a prescription for them then rush them out the door, you’ve got to take time to let that person sit there and tell you what’s happening … (GP4)

Several GP participants highlighted that they generally do not have adequate time to properly address patients’ supportive care needs in one consultation, for example: ‘No, no you never have enough time …’ (GP1). Although participants acknowledged that longer appointments can be arranged, often this can be logistically challenging:

… the average consultation length is between ten and fifteen minutes and yes you can make a double appointment … but often that is not possible because things happen quickly and at short notice, it’s not always possible to plan these things. (GP1)

GPs acknowledged that inadequate consultation time could be a particularly significant barrier to the provision of supportive care within bulk billing practices:

… where there’s a lot of socio-economic need and everyone’s being bulk billed then there’s about five or six minutes for each consultation and it would be very challenging, I think, to be able to then find the time for each person in that scenario … (GP4)

… if you’re sort of one of those bulk billing centres and you only really have those single appointments then you’re absolutely not going to be able to touch on these things appropriately, there’s no way. (GP6)

The time-consuming nature of addressing supportive care needs was felt to be compounded by the Medicare (Australian Universal Health Coverage Scheme) funding mechanisms, with participants identifying systemic problems impacting their ability to spend the necessary time addressing supportive care needs:

I guess it’s the constant thing with general practice … you always feel like you’re rushing to some extent and that’s sort of part of the way the system is set up unfortunately. (GP5)

It was clear from GP responses that the long appointments required for addressing supportive care needs are not practically or adequately supported in the Medicare system:

… the set up with the MBS [Medicare Benefits Schedule] item numbers isn’t great for long appointments … even if they book them long, they end up being over 40 minutes … and the time slot has been half an hour and you’re there at 50 minutes and you have to end the consultation but you’re still only able to charge that 44 in the MBS thing … I do it all the time but some doctors might not be as willing and it does have a ramification on you, as an individual. (GP6)

Furthermore, one participant expressed how inadequate Medicare funding also impacts PNs:

… some surgeries, if every appointment isn’t fully booked with a patient that they can bill, they’re losing money … that comes down also to funding of general practice, you know, there’s no [MBS] item numbers now for PNs … in general practice, you can’t bill anything unless a doctor has seen the patient. (PN5)

Despite the barriers associated with MBS items for PNs, several PNs discussed how they often have adequate time to address supportive care needs, particularly compared to their GP colleagues:

I probably feel as though more so than not, I do have adequate time … I think when they’re sometimes in with the doctor … they could feel like they’re rushed … (PN1)

I think that we as nurses, we have more time to be able to explore that a little bit more and how their diagnosis is affecting not only them but their family. (PN7)

The need to better utilise PNs was a view held by several participants, ‘… it’s like practices really don’t allow their nurses to be used fully and some of the stuff we do it’s like non-tangible stuff …’ (PN5). Similarly, one GP felt that the designated role that PNs are assigned for doing General Practice Management Plans is an improper use of their nursing expertise:

… we have nurses employed simply to do care plans and make sure the paperwork is absolutely correct which is a ludicrous situation. Nurses should be doing nursing things, not administrative paperwork. (GP1)

The community liaison worker role, funded by one practice, provides an opportunity to support PNs in this role, particularly as PNs perceived that the General Practice Management Plan consultations were valuable for addressing supportive care needs:

… so, a care plan [General Practice Management Plan] is a perfect time to be able to talk through, just go through everything that is affecting that patient so discussing every aspect of their health … (PN7)

Challenges in the provision of supportive care that are unique to cancer survivors within diverse populations, including vulnerable populations and non-metropolitan regions, were also identified.

GPs and PNs identified challenges in the provision of supportive care for cancer survivors from vulnerable populations, including cancer survivors with an intellectual disability, mental health conditions, or childhood and older cancer survivors. For example:

… we’ve got a patient who has been a long term mental health patient … he has had an extension of a primary tumour that he had many years ago … lives in poor housing, low-socio-economic, low intellect … so trying to advocate for him and make sure that he’s got all the supports in place that’s necessary for his wellbeing as much as we’re able to. (PN6)

… they might need to be able to get to the toilet, or have a commode, or be fed or have some form of nutrition … as an out of hours doctor you were called in on the weekends with cancer patients and their elderly relatives that were looking after them, wife or husband, couldn’t manage them anymore because of these needs. (GP1)

Participants also recognised challenges with managing the needs of cancer survivors from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. One GP considered professional translation services useful; ‘We have a translator, and we organise family meetings. That’s the way we try to solve the problem and it actually works very well’ (GP7). Another GP (GP2) noted how consultation time constraints and low health literacy are additional barriers to managing supportive care needs of cancer survivors from this group.

GPs and PNs identified additional challenges faced by cancer survivors living in non-metropolitan regions due to accessing support services. Lack of transportation to metropolitan health services was regarded as a significant barrier for individuals in these regions, ‘… some of these people, imagine if they were single or on their own, how would they get to town, so they need to organise that’ (PN6). The lack of available services in non-metropolitan regions was recognised as a barrier to the provision of supportive care:

I’ve got a couple of patients at the moment and the women are like in their forties ... really unwell with their cancer and there’s just hardly any services for them and particularly up in the hills, and you’ll find this the more rural you go … if they’re not well enough to drive, you know, to the suburbs, then your options really, really decrease up here. (PN5)

This was exceptionally difficult for older cancer survivors, even in areas close to metropolitan areas:

Often, it’s not just the medical side of things, so it’s the transport, getting them to their treatments … a lot of them, particularly live up in the hills, they don’t like driving down to town anymore … so getting them to treatments can be difficult. (PN5)

Participants working in non-metropolitan regions would endeavour to refer cancer survivors to local services to avoid lengthy travel, if possible:

… for someone that’s not feeling well, and you know is going through that, doesn’t want to be doing extra trips to town, so we do stick to our local area even if that is minimal resources available. (PN4)

Barriers to providing quality supportive care relating to a lack of information and knowledge were identified. The desire for more information was explored in three subthemes: (1) management of cancer survivors, (2) centralised access to patient information, and (3) available cancer services.

Both GPs and PNs expressed a desire for more information and education on managing supportive care needs once identified. GPs described their capacity to manage physical side effects of cancer treatment with appropriate information from specialists:

I think very clear advice from oncologists about how to manage physical symptoms and when to, I guess you know, be alarmed … so I’m talking about side effects from treatments. (GP4)

While GPs felt less confident in managing certain physical needs of cancer survivors without appropriate guidance, PNs expressed uncertainties on how to manage the more holistic needs of patients:

… like even a lady … she asked me, ‘how much do I tell my children?’, ‘what should I tell my children?’ And I’m like, well I feel like someone that may have more experience with this is better to explain that to you … we have quite good relationships with the people that we’re dealing with, but we don’t have the skills or the knowledge. (PN4)

The community liaison worker highlighted the importance of addressing social needs to appropriately manage supportive care needs and the ability of her role to ‘identify and support relevant services for social care needs’, representing a key aspect of SCN management.

PNs expressed a desire for professional development relating to supportive care needs of cancer survivors. One PN expressed the need for ‘upskilling and educating more nurses and doctors to look at the bigger picture of their patients’ (PN5). Education appeared to be a commonly held need which could address ambiguity relating to the various needs of cancer survivors:

… offering ongoing professional development opportunities for people … it has to be an ongoing thing that highlights or brings to the forefront of people’s minds what cancer patients’ needs are. (PN6)

PNs identified barriers in the provision of supportive care relating to a lack of access to information about patients’ cancer care from other healthcare providers. Patient care information was seen as a facilitator for improving SCN management, and there was a desire for a more comprehensive understanding of the available supports for patients, both within and outside of health care:

Documentation, so that’s the other thing in general practice, you have no idea who or who else is involved in your patients’ care unless you actually sit down with them and say, ‘what other specialists are you seeing?’, ‘what other allied health professionals?’, you know, like, ‘do you go to church or belong to any clubs and things?’ … Like, there’s nowhere where that information is sort of written in one place … (PN5)

The community liaison worker addressed patient need for social support services to enable the doctor to ‘get a holistic picture of the patient’. This was facilitated through good communication within the practice and between the patient and the community liaison worker where the community liaison worker provides ‘an additional channel between the doctor and the patient’. The community liaison worker also highlighted the benefits of centralised access to patient records beyond tertiary information, ‘ACAT [Aged Care Assessment Team] assessment reports are not routinely sent to GPs, despite this information being incredibly useful’. The community liaison worker had the time to enable access to these documents to make this information available to the patients’ primary care team.

One PN described how she did not have access to patient information from within her own practice and how she is often unaware of a cancer diagnosis:

I don’t think as practice nurses, we don’t get that information come through to us, so until they sit and talk to us and tell us what’s going on, we don’t actually know … because all the documents go through to the GP … so, I may not realise until they actually come in and … I am giving them their treatment or … for a flu injection or care plan, that this is actually going on in their life … (PN2)

In addition to a lack of knowledge about patients’ cancer care, participants highlighted lack of awareness of available support services for referrals. PNs also expressed a lack of awareness of how to access services, ‘… to be honest I wouldn’t really know how to access it … palliative care, help at home, showering, medications …’ (PN2). A sense of helplessness was felt concerning an inability to provide appropriate supports:

It is difficult for me, like if they say to me that they ‘need this’ or ‘I’m struggling with this’, how I get that information, how I can support them … it’s really hard and I struggle with ways in which I can support them other than being there. (PN4)

GPs felt that information on available services had to be actively sought, ‘if there are services that are available from hospitals it would be great to receive information on that…instead of us needing to kind of find out for them’ (GP4), or learnt from personal experience outside of professional practice:

I didn’t know about some of these exercise programs that were available … if it wasn’t for the fact that my [spouse] has been through the sort of cancer journey and that was how I learnt about that, and I’ve been practicing as a GP for fifteen years. (GP3)

Participants identified that having a list of available services is a facilitator for supportive care:

As a GP you need to be aware of a range of services available, and this is an issue … there used to be printed copies of available services which were good, but these get outdated too quickly now. (GP9)

This was considered a potentially valuable resource for both health care professionals (HCPs) and patients.

The community liaison worker additionally discussed the change in social service provision to predominantly online as a barrier to managing social supportive care needs:

There was a service at … [location] …that housed all social services. So, you could send people there confident that they would get the help they needed. [It] had all the services like NDIS [National Disability Insurance Scheme] in the one place, now they are all online which makes it hard for some people. (CLW)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the barriers and facilitators to identifying and managing supportive care needs experienced by individuals with a history of cancer. Thematic analysis revealed four key themes identified as impacting the provision of supportive care in general practice: (1) identification of supportive care needs, (2) time and provision of supportive care, (3) challenges in supportive care for diverse populations, and (4) desire for more information.

A general lack of knowledge relating to identifying cancer supportive care needs was notable across all participant interviews, with an insufficient understanding of cancer protocols, pathways, and available services creating barriers to appropriate supportive care. Another study of Australian general practice team members also identified a lack of accessible frameworks for understanding survivorship care (Fox et al. 2022). Australia has a range of Optimal Care Pathway (OCP) guidelines designed as easy-to-follow reference guides to ‘Best Cancer Care’ for HCPs and consumers. Our study suggests these guidelines have not supported general practice involvement in managing supportive care needs. Interventions to improve OCP use in general practice have led to clinicians reporting increased confidence in the use and awareness of OCPs, as well as increased service referrals (Cancer Council 2021). OCPs could be extended to support identifying available services to address supportive care needs, which participants in our study highlighted as a barrier to managing supportive care needs.

When supportive care needs were identified, practical barriers such as time were recognised as significant challenges to management. Short consultation times, partly due to Medicare funding processes, were highlighted. Time and resource constraints have previously been identified as barriers to providing broader survivorship care (Fox et al. 2022). Medicare funding of general practice in Australia has become increasingly unsustainable and remains a significant challenge for primary care providers to deliver comprehensive supportive care. Different practices may also face additional challenges: fewer GPs opt to bulk bill due to the Medicare rebate freeze (Tsirtsakis 2022). However, this may be ameliorated with a recent budget commitment by the Australian Federal Government to increase Medicare funding for longer GP consultations.

PNs within our study believed they were well-placed in their roles to deliver supportive care to their patients with cancer, mainly through General Practice Management Plan consultations. Evidence suggests PNs are underutilised in cancer survivorship care (Fox et al. 2022) and that more efficient use of their role to support GPs is cost-effective and can aid in general practice workforce issues (Afzali et al. 2014). Patients value these PN consults because they provide a relaxed environment with additional time to discuss concerns (Young et al. 2016). Supported by adequate Medicare funding, further development of the PN role for cancer supportive care through General Practice Management Plan consultations may be an effective means to identify and manage supportive care needs.

Challenges in communication with CALD cancer survivors were recognised as a barrier to identifying supportive care needs. Communication difficulties, poorer patient health literacy, and lack of cultural awareness by HCPs can all impact on the delivery of cancer care (Komaric et al. 2012). Optimising other factors that influence the provision of supportive care, such as adequate Medicare funding for longer consultations, may extend benefits to cancer survivors from CALD populations. Difficulties in the provision of supportive care for cancer survivors living in non-metropolitan areas, including areas on the periphery of major cities, were also highlighted. Addressing the issue of unequal access to cancer services requires increasing local cancer services in regional areas. However, it is important to recognise that merely addressing geographic barriers is insufficient, and other access gaps, such as long wait times, must also be considered.

Our study’s participants highlighted how centralised access to patient medical records could facilitate better identification and management of cancer supportive care needs. Currently, more than 90% of Australians have an electronic health system profile called My Health Record (MHR), which can be accessed by the individual and HCPs (The Australian Digital Health Agency 2021). As of April 2019, 92% of general practices were connected to MHR (Australian Digital Health Agency 2019) and 91% of public hospitals (Australian Digital Health Agency 2020) in 2020 actively used the MHR system. With high levels of access to the MHR system, intervention research across all healthcare settings may inform increased utilisation of the system to provide HCPs with a more detailed picture of patient care (Metusela et al. 2023). The use of electronic health systems can help facilitate communication and information-sharing between HCPs and has the potential to improve supportive care need management, as evidence supports the use of electronic health systems for the management of chronic diseases, including cancer (Paydar et al. 2021).

Overlap between the themes in our analysis was noted: for example, the desire for enhanced correspondence from tertiary care about identified supportive care needs (Theme 1) and more information through centralised access to patient records (Theme 4). This overlap emphasises that addressing challenges in identifying and managing supportive care needs within general practice requires a holistic approach. Australian cancer survivors desire a model of cancer care that considers the GP a part of the treating team (Nababan et al. 2020). Information sharing across healthcare settings is a key factor that influences the delivery of supportive care in general practice. This barrier may be mitigated by the inclusion of GPs and PNs in multidisciplinary team meetings with oncologists (Nababan et al. 2020) and greater clinician use of systems such as MHR.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that participants were recruited broadly across South Australia, New South Wales, and Victoria, from major cities, inner and outer regional areas, and practices serving communities of different socio-economic advantage. While the primary care funding model is federally administered and therefore consistent across states and territories, tertiary cancer services are funded by the states and territories and may therefore differ. The National Optimal Care Pathways support consistency of services across Australia suggesting that our findings have applicability in other contexts. Another strength of this study was the unique perspective provided by including an interview with a community liaison worker. This role provided a mechanism to improve communication between the patient and the doctor, obtain additional patient information from other health and social services, and facilitate the management of social supportive care needs for cancer survivors. Several attempts were made to recruit GP participants from large bulk billing practices in more disadvantaged areas; however, these were unsuccessful. Future research could develop a survey based on the themes identified in the present study to target a more extensive sample of primary care providers across Australia to represent the socio-economic and geographical variation. The interviewers did not have experience working in primary care.

Conclusions and future recommendations

This study examined the barriers and facilitators associated with routine supportive care management for cancer survivors in general practice. We identify key barriers primary care providers face, including challenges in identifying supportive care needs, time constraints, supporting diverse populations, and needing additional information. We also highlight system limitations, including inadequate communication between tertiary care and general practice and the lack of information available to primary care providers regarding available services to meet cancer survivors’ supportive care needs. Targeted efforts such as information sharing across healthcare settings and centralised access to patient information and available services, could improve the effective management of supportive care in general practice.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Afzali HHA, Karnon J, Beilby J, Gray J, Holton C, Banham D (2014) Practice nurse involvement in general practice clinical care: policy and funding issues need resolution. Australian Health Review 38, 301-305.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Digital Health Agency (2019) 9 out of 10 general practices signed up to My Health Record. Available at https://www.myhealthrecord.gov.au/news-and-media/media-releases/general-practices-signed-my-health-record [accessed 27 September]

Australian Digital Health Agency (2020) Public hospitals using the My Health Record system. Available at https://www.myhealthrecord.gov.au/about/who-is-using-digital-health/public-hospitals-using-my-health-record-system [accessed 27 September]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Cancer. AIHW, Canberra. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/cancer

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C, Schrag D (2017) Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318, 197-198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bellas O, Kemp E, Edney L, Oster C, Roseleur J (2022) The impacts of unmet supportive care needs of cancer survivors in Australia: a qualitative systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care 31, e13726.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Braun V, Clarke V (2022) Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology 9, 3-26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cancer Council (2021) Optimal care pathways: for general practitioners and primary care staff. Available at https://www.cancervic.org.au/get-support/for-health-professionals/optimal-care-pathways#section-2 [accessed 16 March]

Deckx L, Chow KH, Askew D, van Driel ML, Mitchell GK, van den Akker M (2021) Psychosocial care for cancer survivors: a systematic literature review on the role of general practitioners. Psycho-Oncology 30, 444-454.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Emery JD, Jefford M, King M, Hayne D, Martin A, Doorey J, Hyatt A, Habgood E, Lim T, Hawks C, Pirotta M, Trevena L, Schofield P (2017) ProCare Trial: a phase II randomized controlled trial of shared care for follow-up of men with prostate cancer. BJU International 119, 381-389.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fitch MI (2008) Supportive care framework. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal 18, 6-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fox J, Thamm C, Mitchell G, Emery J, Rhee J, Hart NH, Yates P, Jefford M, Koczwara B, Halcomb E, Steinhardt R, O’Reilly R, Chan RJ (2022) Cancer survivorship care and general practice: a qualitative study of roles of general practice team members in Australia. Health & Social Care in the Community 30, e1415-e1426.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gordon J, Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Scott A, Harrison C (2022) General practice statistics in Australia: pushing a round peg into a square hole. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 1912.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jefford M, Koczwara B, Emery J, Thornton-Benko E, Vardy JL (2020) The important role of general practice in the care of cancer survivors. Australian Journal of General Practice 49, 288-292.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jefford M, Howell D, Li Q, Lisy K, Maher J, Alfano CM, Rynderman M, Emery J (2022) Improved models of care for cancer survivors. The Lancet 399, 1551-1560.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kaegi-Braun N, Schuetz P, Mueller B, Kutz A (2021) Association of nutritional support with clinical outcomes in malnourished cancer patients: a population-based matched cohort study. Frontiers in Nutrition 7, 603370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Komaric N, Bedford S, van Driel ML (2012) Two sides of the coin: patient and provider perceptions of health care delivery to patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. BMC Health Services Research 12, 322.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD (2016) Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research 26, 1753-1760.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Meiklejohn JA, Mimery A, Martin JH, Bailie R, Garvey G, Walpole ET, Adams J, Williamson D, Valery PC (2016) The role of the GP in follow-up cancer care: a systematic literature review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 10, 990-1011.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Metusela C, Mullan J, Kobel C, Rhee J, Batterham M, Barnett S, Bonney A (2023) CHIME-GP trial of online education for prescribing, pathology and imaging ordering in general practice – how did it bring about behaviour change? BMC Health Services Research 23, 1346.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Nababan T, Hoskins A, Watters E, Leong J, Saunders C, Slavova-Azmanova N (2020) ‘I had to tell my GP I had lung cancer’: patient perspectives of hospital- and community-based lung cancer care. Australian Journal of Primary Health 26, 147-152.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine 89, 1245-1251.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Paydar S, Emami H, Asadi F, Moghaddasi H, Hosseini A (2021) Functions and outcomes of personal health records for patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Perspectives in Health Information Management 18, 1l.

| Google Scholar |

Roseleur J, Edney LC, Jung J, Karnon J (2023) Prevalence of unmet supportive care needs reported by individuals ever diagnosed with cancer in Australia: a systematic review to support service prioritisation. Support Care Cancer 31, 676.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

The Australian Digital Health Agency (2021) My Health Record: statistics and insights. Available at https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/myhealthrecord-statistics-august21.pdf [accessed 27 September]

Tsirtsakis A (2022) True extent of poor Medicare indexation revealed. Available at https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/professional/true-extent-of-poor-medicare-indexation-revealed

Young J, Eley D, Patterson E, Turner C (2016) A nurse-led model of chronic disease management in general practice: patients’ perspectives. Australian Family Physician 45, 912-916.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |