Senior staff experiences of implementing a reablement model in community care

Sarah J. Prior A * , Hazel Maxwell B C , Marguerite Bramble D E , Annette Marlow E , Douglass Doherty F Steven Campbell EA

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

In 2018, a community care organisation in Northwest Tasmania collaborated with University of Tasmania researchers to develop and implement a strategy for incorporating a reablement-based model of care into their service delivery model as a core organisational approach to care. This study aimed to investigate the long-term outcomes from the initial reablement education to improve our understanding of the needs of staff and clients of community care organisations.

The research explored the impact of reablement on client outcomes and how reablement can be translated across organisations. A qualitative research method was utilised to explore experiences of senior staff 2 years after the first reablement education sessions. Two focus groups were held 4 weeks apart. Nine senior staff participated in focus group one and seven in focus group two.

Three key themes emerged; reablement needs an appropriate governance and organisational strategy; reablement is a beneficial practice; and strong organisational culture supports reablement. Achieving long-term outcomes involves integrating reablement into working practices and this remains challenging due to organisational constraints.

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence that shifting underlying practices in community care from ‘doing for’ to ‘doing with’ involves a major change of behaviour and practice for individuals and organisations.

Keywords: community care, implementation, model of care, organisational change, patient-centred care, service delivery, staff experience.

Introduction

Reablement is defined as an innovative approach to improving in-home care services for older adults at risk of functional decline by re-orienting care away from treating disease and creating dependency to maximising independence (Social Care Institute for Excellence 2020). A recent review of integrated care identified that active ageing was enhanced for older people when they felt motivated to engage in health goals, their preferences were taken into consideration, and they were supported in their wellbeing through a relationship with a key community worker (Karacsony et al. 2022). Furthermore, the World Health Organization (WHO)defines healthy ageing as the ‘process of developing and maintaining functional ability that enables well-being in older adults’ (World Health Organization 2017). Functional ability consists of the intrinsic capacity of a person, the relevant environmental characteristics, and the interaction between them (World Health Organization 2017). Reablement is intended to deliver both person-centered and goal-oriented care that encourages clients to remain as independent as possible for as long as possible, and to actively participate in home-life, community, and society (Campbell et al. 2022; Ratcliffe et al. 2022; Rostgaard et al. 2023). Internationally, reablement has been developed to support integrated frameworks that achieve long-term care and assistance across community settings that both align with the needs and goals of the client and consider staff experiences. This may include the involvement of staff in training, goal-setting, and working with clients in different ways (Doh et al. 2020; Bramble et al. 2022). Applying a holistic, person-centred approach is central to implementing the reablement model of care. It requires all community care staff across an organisation to understand the importance of personhood; gain input from the individual client, family, and carers; appreciate the client’s social networks; and take a collaborative approach to enhancing individual care (Hjelle et al. 2016; Gyllensten et al. 2020; Jobe et al. 2020; Karacsony et al. 2022). The reablement model of care aligns closely with the person-centred approach through collaboration between health and social care professionals (staff) and clients and their families. This collaboration has been shown to improve physical and psychological health status, increase capability to self-manage, and reduce length of stay in acute care (Lewin et al. 2013; Coulter et al. 2015).

Underpinning the philosophy and practice of reablement, therefore, is the principle of empowering and enabling clients to make choices about their own wellbeing goals as part of shared decision making (Karacsony et al. 2022). Client choice is also central to staff engagement in the coordination and delivery of care services to meet the needs of clients and families, as part of the integration of health and social care alongside an associated interdisciplinary plan (Jobe et al. 2020). All staff across the organisation can then work together to deliver care that is responsive, person centred, and respectful. These support services may include home maintenance, domestic assistance and the provision of personal care, respite care, and social support (Maxwell et al. 2021). The benefit to clients, their carers, and their families can be seen through a change in staff behaviour as a result of education and leadership development, with a more reablement-focused approach to service delivery and care (Campbell et al. 2022). Other benefits are increases in staff job satisfaction and staff retention, reflecting an overall positive development in organisational culture (Rostgaard 2018).

Countries that have implemented reablement into their health and social care services have taken distinctive approaches suited to their individual needs. However, some features shared across countries include holistic care assessment and comprehensive care planning and care coordination (Wodchis et al. 2015). Reablement has also been commonly utilised in community care services to assist clients to both maintain and regain independence when they have experienced functional decline as part of the ageing process or as the result of an acute medical incident or chronic medical condition. Previous studies have reported that the effects of reablement on personal activities of daily living (PADL) are positive, with improved self-perceived performance and satisfaction with performance in prioritised daily activities that are sustained on a long-term basis (Tuntland et al. 2015; Rooijackers et al. 2021a). Rooijackers et al. (2021a) found that community care staff’s compliance with reablement program meetings was as high as 73.4% and that staff supported reablement and valued its practical elements and team involvement. They also found that informal carers increased their knowledge, attitude, and skills in the practice of reablement and received both peer and organisational support for its implementation (Rooijackers et al. 2021a).

Despite the wide range of online learning tools and short courses around the delivery of reablement as an approach to care, globally, there is little evidence evaluating the outcomes of these educational initiatives and their implementation and sustainability in organisations. One study in Taiwan examining the health literacy of home health professionals delivering reablement services found that to be competent in reablement requires unique skills focused on increasing older adults’ participation in everyday activities and interdisciplinary collaboration (Yu et al. 2022). This study supports the view that further developmental work is required to integrate the components of interdisciplinary training programs in individual organisations, depending on individual client, family, and organisational expectations (Liaaen and Vik 2019; Karacsony et al. 2022).

This study, therefore, aimed to investigate the value of a reablement model of care, implemented following a bespoke training and education program, to better understand the needs of staff and clients of community care organisations, from the senior staff perspective. The question that guided this research is how do senior staff experience a co-designed, bespoke reablement model of care?

Materials and methods

Setting

In 2018, the University of Tasmania and a local regional community care organisation, Family Based Care Tasmania, collaborated to develop and implement a strategy for ensuring a reablement-based model of care was incorporated into the service delivery model and that reablement was recognised as a stand-alone organisational approach to care (Prior et al. 2020). This strategy involved the development of training and educational materials (including videos, role play, and workshops activities), using co-design (involving community care workers cooperating to design activities), around the concept of reablement and how it applies to community care. This process also involved an evaluation of the experiences of all staff who participated in the training and subsequently utilised their new knowledge and understanding in their work with clients in home care settings (Maxwell et al. 2021).

Method

A qualitative research method was utilised to explore the experiences of Family Based Care’s senior staff 2 years post the initial reablement training and education program.

Participants

Eleven senior staff from Family Based Care in coordination and leadership roles accepted an invitation to participate in this study. Eight care coordinators, two managers, and one policy team member comprised the overall group. Staff were identified by their current role within the organisation and were recruited via email, sent internally within the organisation, inviting them to participate in an evaluative study.

All staff recruited for this study were involved in the implementation of the reablement model of care through a range of activities. Care coordinators worked alongside direct care workers to incorporate reablement into client care plans and activities of daily living through training and mentoring. Staff in leadership/management and policy roles facilitated the implementation of reablement as a core business value by creating awareness, acceptability, and organisational focus on the principles of reablement within the overall Family Based Care business model.

Data collection

Two 2-hour focus groups were held 4 weeks apart in February 2021 and March 2021. Eight care coordination staff, one manager, and one policy staff member participated in focus group one (nine face to face and one via tele link) and six care coordination staff and two managers participated in focus group two (seven face to face and one via tele link). All participants provided consent to be involved, and both focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed for data analysis.

The focus groups were facilitated by two University of Tasmania researchers with an additional researcher present for audio recording and note taking. Conversation was directed to discussion around two key questions:

Data analysis

Focus group data were analysed using a general inductive thematic analysis method in two phases based on a qualitative analysis tool described by Thomas (2006). This method was selected to establish clear links between the data and the aim of the research and develop a framework of experiences to guide the implementation of reablement more broadly in health and community care organisations. Three guiding steps were utilised.

Explore the core meanings evident in the text, relevant to the research objectives.

Organise text into categories relevant to the research objectives.

Describe the main themes based on the categories.

Two members of the research team coded the raw data to identify categories that illustrated meanings, associations, and perspectives of the data. The coding was done on a line-by-line basis, identifying segments of text pertaining to similar ideas. The researchers met on several occasions to compare and scrutinise categories, and final themes were ascertained through revision and refinement of the categories.

Results

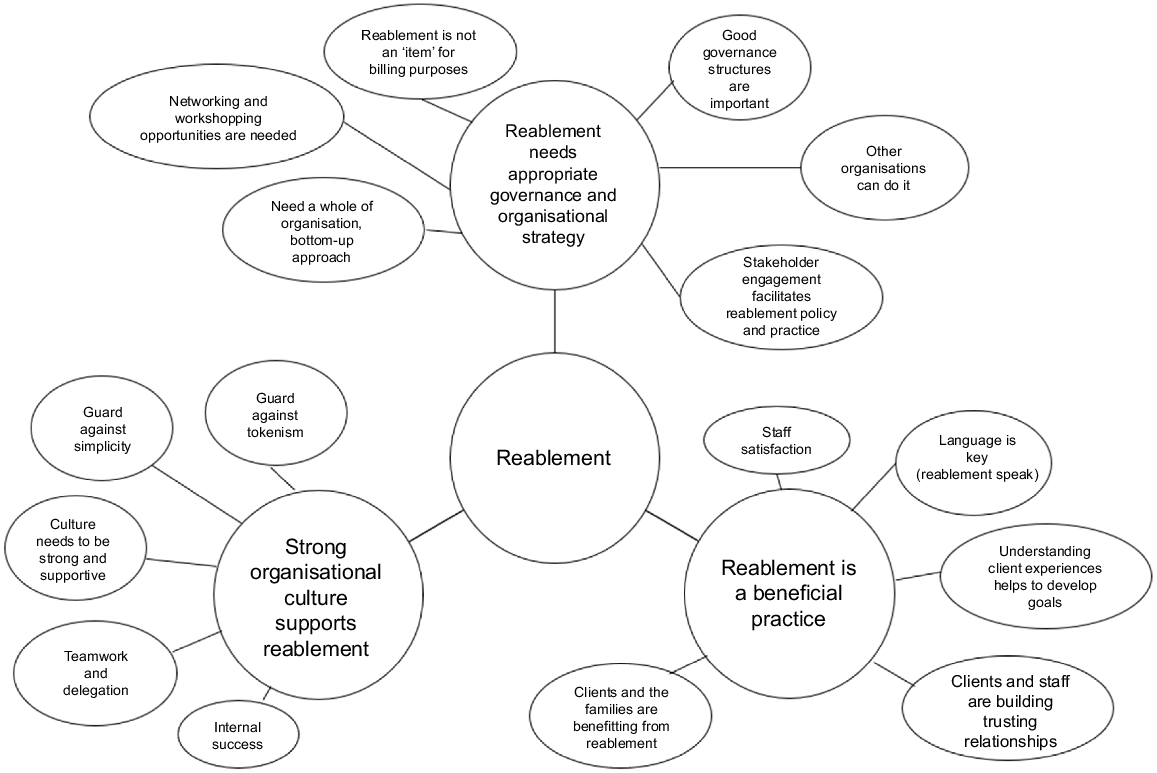

Staff from Family Based Care provided in-depth discussion of how reablement has become a routine part of their daily activities in the care of clients by the direct care workers from the perspective of senior staff and indirectly through organisational activities such as training, formal and informal feedback, and policy development. Discussion centred around several categories within major themes, and three key themes were extracted. Fig. 1 shows how each theme was derived from the original coding categories.

Categories and theme development. This image provides an overview of the categories and themes that were developed as part of the data analysis.

Key themes

Senior staff described reablement as an organisational value and an engrained model of providing client care that needs both structure and oversight for sustainability. Senior staff discussed governance in terms of their focus on who was responsible for making sure that ‘reablement was done’ and who is accountable for behaviours and actions that are not aligned with the reablement framework. They highlighted the development of a reablement team, who continue to meet regularly with a purpose to shine a light on good reablement practice and provide induction and orientation, ongoing training, and education to staff who were not as confident in reablement as the organisation would like, based on self-assessment and feedback. There was consensus that the actual practice of implementing or embedding reablement as a core value starts with the development of processes in the care planning stage of client assessment. Developing these processes and associated activities has become the responsibility of the reablement team within the organisation, with feedback from direct care workers, clients, and their families as a quality assurance mechanism. Despite this process, feedback indicated that some challenges were still experienced by senior staff. Some clients’ families believed that direct care workers were not doing their jobs if they did not carry out tasks for clients and instead guided the clients to do the task themselves.

There have still been some comments about direct care workers not doing their jobs in terms of not doing for their clients; mostly from families. (S5)

From a team leader (care coordinator) perspective, reablement as a strategy for quality improvement was slow to get off the ground formally due to time restraints. The organisation had also taken steps to orientate staff into a reablement way of ‘thinking and doing’ utilising a pre-employment questionnaire and providing an organisational induction specifically focused on the principles of reablement. This included normalising reablement as a ‘way of working’ rather than a particular model or framework.

From a macro-economic perspective, senior staff expressed concern about the cost of home and community-based aged care packages for individual clients and families. They felt that the government funding allocated to care packages was insufficient and that there is a gap between the real cost of home and community-based aged care packages and the allocations made by successive governments. As an example of how staff felt reablement was misconstrued by policy makers, they suggested ‘Reablement is not an ‘item’ for billing purposes’ (S2) and ‘The Government is acting in the opposite way to reablement’ (S1) meaning that the government is only interested in the financial outcomes, not the client outcomes.

In aged care in general, participants highlighted that a large portion of funding is allocated to residential facilities and only a relatively small portion to community care and community services. This does not reflect the organisational values driven by a reablement philosophy. Staff feel that they are working hard to keep their clients out of residential facilities and in their own homes for the benefit of their clients, but at a higher level, there was no organisation reward or incentive to continue doing so. Despite this, staff were committed to doing the best for their clients. Staff who worked directly with clients in support or coordination roles described ways they had developed a reablement leadership group who continued to encourage staff to work in a reablement-focussed way.

The group took charge and moved forward – reablement is an intrinsic concept that was embedded well. (S4)

The primary focus of the discussion in both focus groups was that reablement is a beneficial practice for staff, clients, and their families, from the staff perspective. They described feelings of satisfaction and pride when helping clients do for themselves rather than doing for them and wanted us to understand how reablement had changed the way in which they work and think. Clients were regaining their confidence to do things that made them feel ‘useful’ and able to be independent. Organisational benefits were also described in terms of drawing in new families based on the reablement model – the organisation was driven to help keep people in their own homes for longer, with a view to improving their quality of life.

Senior staff who worked directly with clients in coordination roles described how they, as well as their direct care workers, had developed ways to break down tasks to ensure that there were opportunities for client participation in singular components rather than whole tasks. This helped clients to re-learn tasks slowly or simply kept clients involved in their routine tasks without overwhelming them. Family Based Care focuses on the capability of clients rather than the disability – staff termed this an ability model, not a deficit model, in line with reablement philosophy. This was seen as a positive for one staff member.

This was a highlight for me – the notion of focusing on the capability of the client, rather than the disability. (S7)

Staff felt that the eligibility of clients for the Family Based Care programs has traditionally focused on deficits and how they could be ‘filled’ rather than the strengths of each client and how they could be maximised. Staff talked about using these strengths to help clients become more independent in their homes and continue doing things for themselves. The following quotations show some of the benefits of reablement.

My client can use the washing machine but can’t remember which buttons to push, so I made a sign that tells him and now he can do his own washing. (S5)

My client can wash the dishes but has trouble with large pots, so I do the pots and she does the rest. (S6)

Family Based Care staff felt that they were leading best practice when it came to reablement-based models of care. It was noted that one client had been in a residential aged care facility, but their family bought them back home and worked with Family Based Care to ‘re-able’ them. Another example from one direct care worker was helping a client to re-learn how to cook his own meals, which has meant that this client no longer needs the services of the organisation. This was considered to be a success story by the organisation and the staff, despite the organisation ‘losing’ a client. Senior staff expressed deep satisfaction at being able to help people do the things they want to do, rather than simply doing things for people (their clients).

Clients are regaining their confidence. (S4)

Family Based Care senior staff described their strengths in delivering a reablement model of care in terms of being a dynamic and engaged team with direct support from internal management, including the chief executive officer, and opportunities to expand their skills and knowledge through cultural change. There was a consensus among senior staff that reablement can be more complex than the traditional approach to caring which only involves ‘doing for’. The ‘doing with’ approach is facilitated by working as a team, focusing on improving client outcomes, one step at a time. The organisation and senior staff described their teams taking ownership of the reablement model of care and embedding it as a core process within their roles.

The process isn’t simple, but it has become simple because of the ownership of Family Based Care. (S3)

Senior staff felt that there was a genuine embedding of reablement principles within and throughout their organisation in direct care as well as indirect care. This has been facilitated through support at the direct care worker level, care coordination (senior staff) level, and through upper management. Reablement was considered a value-based model, rather than just something that needs to be ticked off.

Reablement is not just a tick box exercise that organisations should be doing. It requires education, teamwork, a good implementation plan, and sustainability. (S3)

Additionally, senior staff discussed approaches for translating their values and changes across other organisations, highlighting limited opportunities for engagement across community organisations as a barrier to systemic change. Senior staff believed that for reablement to be successfully implemented, based on their own experience, an organisation needed to guard against tokenism, guard against simplicity, and ensure a whole of organisation, bottom-up approach to change.

Discussion

The topics that were explored as part of this study focused on the benefits and limitations of implementing a reablement model of care into a community care-based organisation. The findings suggest three key themes to demonstrate the long-term benefits of integrating a reablement training and education program into practice in a community care organisation. From a macro-economic perspective, governments worldwide need to prioritise the best use of resources for our ageing populations across community and residential care and focus on their preferences and needs to achieve quality of life (Ratcliffe et al. 2022). Recent research has provided further evidence that a major priority for older people is to remain mobile and independent at home for as long as possible, considering current and future health needs (Ratcliffe et al. 2022; Rostgaard et al. 2023).

Senior staff highlighted that for long term success in reablement practice to continue, organisational leadership must ensure that an appropriate governance and organisational strategy is in place, supported by a strong organisational culture to support its key principles, highlighted in the first key theme. Senior staff also identified that, from a macro-economic perspective, different models of care such as reablement do not currently align with current government funding that is skewed towards residential care. This was seen as a barrier to the development of organisational values driven by reablement in community care organisations, as all staff felt that they are working hard to keep their clients out of residential facilities and in their own homes. It is clear that reablement models support older people to maintain intrinsic capacity in their home environment and that there are many benefits of reablement despite some initial reluctance of clients and their families to engage with this type of care model.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2017) recommended that all healthcare organisations develop and embed an appropriate governance and organisational structure that places the client at the centre, ensuring the person and their family are supported by a safe environment, good leadership, and a high standard of patient care quality. Focusing on the philosophy of reablement in this way would allow for its integration into core values and processes across the organisation, thus enhancing reablement as best practice care (Masood and Afsar 2017). As suggested in key theme 1 and key theme 3, our findings highlight that culture change is a major influencing factor in the success of embedding reablement into an organisation and support from local and wider leadership groups is instrumental in sustaining meaningful change. Consistent with previous studies, our study found that an organisation may be able to demonstrate success based on outcomes for clients and staff if it has (1) a bottom-up approach to change and (2) structured policy on the implementation and sustainability of new models of care (Bramble et al. 2022).

In both focus groups, senior staff made it very clear that they considered reablement a beneficial practice for staff, clients, and their families. They described feelings of satisfaction and pride when helping clients to regain their confidence and maintain their independence, also noted in previous studies (Maxwell et al. 2021; Rooijackers et al. 2021b). The resulting organisational benefits were an increase in the number of new clients and their families as they heard about the benefits of reablement practice. Previous research has supported the perceived beneficial nature of reablement to staff and clients across organisations (Glendinning et al. 2010; Aspinal et al. 2016; Smeets et al. 2020; Rooijackers et al. 2021a).

Perceived barriers to reablement practices include resistance to change from clients and/or their social network, complex care situations, time pressure, and staff shortages (Rooijackers et al. 2021a). Smeets et al. (2020) found that community care workers need further support from their organisations with mastering skills and dealing with challenging situations to avoid a tendency to ‘take over’ tasks from clients. This focus on staff mastering the skills associated with reablement also ensures that the organisation meets the required aged care standards and quality of life for consumers is maintained (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission 2019; Ratcliffe et al. 2022). Senior staff in our study felt well supported in their skill and knowledge attainment journey within their organisation but also commented on the limited uptake and use of reablement practice more broadly within the health and aged care sector.

The strong and supportive culture depicted within the organisation involving ongoing and regular team meetings together with regular staff supervision sessions helped to reinforce and sustain reablement within the organisation, demonstrated in key theme 3. This ongoing commitment to the notion of reablement is supported by previous research which found that staff who adopt a broader perspective of supporting clients in achieving their goals are instrumental in facilitating reablement practices to become embedded in the culture of their organisations (Rabiee and Glendinning 2011; Maxwell et al. 2021). In particular, Smeets et al. (2020) recommended that offering organisational support to community care workers was important in embedding reablement practice and that establishing a long-term implementation plan was essential. Jobe et al. (2020) focused on the importance of professionals being supported by management in delivering reablement and being involved in the planning process. European experience suggests that ongoing training, especially for new staff, is required to embed reablement practice into an organisation (Rostgaard and Graff 2017; Jobe et al. 2020).

Limitations

This study utilised a small sample of care coordinators from a local community care organisation to explore the barriers to, and enablers of, implementing a reablement model of community-based care. Direct care workers were not involved in this study, but further work will ensure their views and experiences are captured. The research team acknowledges that this study’s results may only be transferrable to geographically similar organisations; however, the principles of support and development are much more translatable. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the voice of the older person, the consumer, is not represented in this study. We plan to continue to work with community care-based clients to seek their experiences in the future.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing body of evidence that moving the focus of community care services long term from ‘doing for’ to ‘doing with’ older adults involves a major shift in understanding and practice, both for individuals and organisations. Achieving long-term outcomes involves ongoing training for all staff, including management and integration with other person-centred models of care. In this way, changes in organisational culture based on sound governance principles can be achieved, with long-term benefits for all staff and clients.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical approval restrictions.

References

Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission (2019) Aged care quality standards. Retrieved from https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/sites/default/files/media/acqsc_aged_care_quality_standards_fact_sheet_4pp_v8.pdf

Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, Tuntland H, Westendorp RGJ (2016) New horizons: reablement – supporting older people towards independence. Age and Ageing 45(5), 574-578.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2017) National model clinical governance framework. Retrieved from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Model-Clinical-Governance-Framework.pdf

Bramble M, Young S, Prior S, Maxwell H, Campbell S, Marlow A, Doherty D (2022) A scoping review exploring reablement models of training and client assessment for older people in primary health care. Primary Health Care Research & Development 23, e11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Campbell SJ, Walsh K, Prior SJ, Doherty D, Bramble M, Marlow A, Maxwell H (2022) Examining the engagement of health services staff in change management: modifying the SCARF assessment model. International Practice Development Journal 12(1), 5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R (2015) Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3, CD010523.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Doh D, Smith R, Gevers P (2020) Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Ageing and Society 40(6), 1371-1383.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Glendinning C, Jones K, Baxter K, Rabiee P, Curtis LA, Wilde A, Forder JE (2010) Home care re-ablement services: investigating the longer-term impacts (prospective longitudinal study). University of York. Working paper No. 2438. Retrieved from https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/Reablement.pdf

Gyllensten H, Björkman I, Jakobsson Ung E, Ekamn I, Jakobsson S (2020) A national research centre for the evaluation and implementation of person-centred care: content from the first interventional studies. Health Expectations 23(5), 1362-1375.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Førland O, Alvsvåg H (2016) The reablement team’s voice: a qualitative study of how an integrated multidisciplinary team experiences participation in reablement. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 9, 575-585.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jobe I, Lindberg B, Engström Å (2020) Health and social care professionals’ experiences of collaborative planning – applying the person-centred practice framework. Nursing Open 7(6), 2019-2028.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Karacsony S, Merl H, O’Brien J, Maxwell H, Andrews S, Greenwood M, Rouhi M, McCann D, Stirling C (2022) What are the clinical and social outcomes of integrated care for older people? A qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Integrated Care 22(3), 14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lewin G, De San Miguel K, Knuiman M, Alan J, Boldy D, Hendrie D, Vandermeulen S (2013) A randomised controlled trial of the Home Independence Program, an Australian restorative home-care programme for older adults. Health & Social Care in the Community 21, 69-78.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Liaaen J, Vik K (2019) Becoming an enabler of everyday activity: health professionals in home care services experiences of working with reablement. International Journal of Older People Nursing 14(4), e12270.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Masood M, Afsar B (2017) Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior among nursing staff. Nursing Inquiry 24(4), e12188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maxwell H, Bramble M, Prior SJ, Heath A, Reeves NS, Marlow A, Campbell SJ, Doherty DJ (2021) Staff experiences of a reablement approach to care for older people in a regional Australian community: a qualitative study. Health and Social Care in the Community 29, 685-693.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prior SJ, Heath A, Reeves NS, Campbell SJ, Maxwell H, Bramble M, Marlow A, Doherty D (2020) Determining readiness for a reablement approach to care in Australia: development of a pre-employment questionnaire. Health & Social Care in the Community 30(2), 498-508.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rabiee P, Glendinning C (2011) Organisation and delivery of home care re-ablement: what makes a difference? Health & Social Care in the Community 19(5), 495-503.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ratcliffe J, Bourke S, Li J, Mulhern B, Hutchinson C, Khadka J, Milte R, Lancsar E (2022) Valuing the quality-of-life aged care consumers (QOL-ACC) instrument for quality assessment and economic evaluation. PharmacoEconomics 40(11), 1069-1079.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rooijackers TH, Zijlstra GAR, van Rossum E, Vogel RGM, Veenstra MY, Gertrudis I, Kempen JM, Metzelthin SF (2021a) Process evaluation of a reablement training program for homecare staff to encourage independence in community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatrics 21, 5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rooijackers TH, Kempen GIJM, Zijlstra GAR, van Rossum E, Koster A, Passos VL, Metzelthin SF (2021b) Effectiveness of a reablement training program for homecare staff on older adults’ sedentary behavior: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of American Geriatric Society 69(9), 2566-2578.

| Google Scholar |

Rostgaard T (2018) Reablement in home care for older people in Denmark and implications for work tasks and working conditions. Innovation in Aging 2(Suppl 1), 174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rostgaard T, Graff L (2017) Reablement in Denmark—Better help, better quality of life? Innovation in Aging 1(Suppl 1), 648.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smeets RGM, Kempen GIJM, Zijlstra GAR, van Rossum E, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Hanssen WAG, Metzelthin SF (2020) Experiences of home-care workers with the ‘Stay Active at Home’ programme targeting reablement of community-living older adults: an exploratory study. Health & Social Care in the Community 28(1), 291-299.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Social Care Institute for Excellence (2020) Role and principles of reablement. Available at https://www.scie.org.uk/reablement/what-is/principles-of-reablement [accessed May 2023]

Thomas DR (2006) A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27(2), 237-246.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Espehaug B, Førland O, Kjeken I (2015) Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics 15, 145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wodchis WP, Dixon A, Anderson GM, Goodwin N (2015) Integrating care for older people with complex needs: key insights and lessons from a seven-country cross-case analysis. International Journal of Integrated Care 15, e021.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

World Health Organization (2017) Decade of healthy ageing 2020–2030. Available at https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing [accessed August 2024]

Yu H-W, Wu S-C, Chen H-H, Yeh Y-P, Chen Y-M (2022) Relationships between reablement-embedded home- and community-based service use patterns and functional improvement among older adults in Taiwan. Health & Social Care in the Community 30(6), e4321-e4331.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |