The feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of screening for frailty in Australians aged 75 years and over attending Australian general practice

Jennifer Job A * , Caroline Nicholson A , Debra Clark B , Julia Arapova C and Claire Jackson A D

A * , Caroline Nicholson A , Debra Clark B , Julia Arapova C and Claire Jackson A D

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Globally, frailty is associated with a high prevalence of avoidable hospital admissions and emergency department visits, with substantial associated healthcare and personal costs. International guidelines recommend incorporation of frailty identification and care planning into routine primary care workflow to support patients who may be identified as pre-frail/frail. Our study aimed to: (1) determine the feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and determinants of implementing a validated FRAIL Scale screening Tool into general practices in two disparate Australian regions (Sydney North and Brisbane South); and (2) map the resources and referral options required to support frailty management and potential reversal.

Using the FRAIL Scale Tool, practices screened eligible patients (aged ≥75 years) for risk of frailty and referred to associated management options. The percentage of patients identified as frail/pre-frail, and management options and referrals made by practice staff for those identified as frail/pre-frail were recorded. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with practice staff to understand the feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and determinants of implementing the Tool.

The Tool was implemented by 19 general practices in two Primary Health Networks and 1071 consenting patients were assessed. Overall, 80% of patients (n = 860) met the criterion for frailty: 33% of patients (n = 352) were frail, and 47% were pre-frail (n = 508). They were predominantly then referred for exercise prescription, medication reviews and geriatric assessment. The Tool was acceptable to staff and patients and compatible with practice workflows.

This study demonstrates that frailty is identified frequently in Australians aged ≥75 years who visit their general practice. It’s identification, linked with management support to reverse or reduce frailty risk, can be readily incorporated into the Medicare-funded annual 75+ Health Assessment.

Keywords: determinants, healthy ageing, hospital avoidance, implementation, older persons, primary care, risk of frailty, screening.

Introduction

The prevalence of frailty is increasing, underpinned by our rapidly ageing population. Frailty can be considered a pre-disability state and physical frailty includes unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, weakness, slow walking speed and low physical activity (Fried et al. 2001). Frequent falls are more common in the frail (Bandeen-Roche et al. 2015) and frailty is associated with potentially preventable hospitalisations, and substantial healthcare costs driven by inpatient, pharmaceutical and long-term care costs (Hoogendijk et al. 2019). In addition, frailty is associated with reduced quality of life, survival and resilience to acute problems when compared with healthier people. In Australia, 16% of the population are aged ≥65 years, and frailty is estimated to affect approximately 25% of this population (Thompson et al. 2018). In general practice, 30% of encounters are with patients aged ≥65 years, which offers an ideal opportunity to assess frailty in this population.

Major international agencies recommend case finding for frailty in older adults as part of routine clinical practice (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2016; Dent et al. 2017). Screening for frailty in the community and provision of multicomponent interdisciplinary interventions have been shown to reverse or reduce frailty and improve physical performance (Cameron et al. 2013; Travers et al. 2019). However, a standardised assessment for risk of frailty is not routine practice in primary care in Australia. The Medicare-funded 75 and over Health Assessment (75+ HA), introduced to Australian general practice in 1999, does not currently include formal frailty assessment (Australian Department of Health and Aged Care 2014). This was highlighted in our previous audit of 348 charts of patients aged ≥75 years, who had completed annual health assessments in 11 general practices in North Sydney and Brisbane South (Job et al. 2023). The audit revealed that only 2% of charts had all five of the FRAIL Scale components (fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illness, weight loss) recorded as assessed. Although patients may be assessed on individual elements of risk of frailty, the use of a validated tool to support identification of risk is not in place. It is also important to consider the capacity of the primary care team to customise their frailty management based on identified components of frailty. Individuals identified as frail or at risk of frailty should be advised, according to individual circumstances, on care and support planning, exercise, nutrition, medication reviews and the need to strengthen social networks (Boreskie et al. 2022).

The FRAIL Scale, developed and validated as a screening tool, is easy for general practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses to apply in a clinical setting, and is based on Fried’s phenotype of frailty elements. These include exhaustion (fatigue), weight loss, measured grip strength and walking speed, and low energy expenditure (Fried et al. 2001). The FRAIL Scale includes five simple questions to identify risk of frailty across five components (Morley et al. 2012):

Feeling fatigued most or all of the time

Resistance against gravity: difficulty walking up 10 steps without resting

Ambulation: difficulty walking 300 metres unaided

Illnesses: having five or more

Loss of >5% weight in 12 months

FRAIL Scale scores range from 0 to 5 (i.e. one point for each component) to give one of three outcomes:

Frail: three or more components present

Prefrail: one to two components present

Robust: zero components present

The FRAIL Scale has been validated in community dwelling populations and has been shown to predict future disability (Morley et al. 2012) and mortality in men and women (Thompson et al. 2020). In the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, the FRAIL Scale predicted future disability over a 15-year period in women and was shown to be suitable for use in longitudinal studies of women aged ≥70 years (Gardiner et al. 2015). Apart from validity and reliability, a practitioner’s choice of a frailty measure needs to take into consideration ease of use (based on time, training, equipment) and whether additional resources are needed for administration (Abbasi et al. 2019). In 2019, the Sydney North Health Network (SNHN) recognised the need to build risk of frailty identification and management into general practice workflows and developed the FRAIL Scale Tool (the Tool).

The aim of the study is to pilot the FRAIL Scale Tool in general practice in two Primary Health Network areas in Australia to assess:

the impact of introducing an evidence-based tool to assess and track risk of frailty in patients aged ≥75 years.

the resources required in the community to support identified need and patient barriers to accessing these management options.

implementation measures including feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness, and barriers and facilitators (determinants) of adoption of the FRAIL Scale Tool in general practice.

Methods

Design

A theory-informed mixed methods study design was used to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and determinants of implementing the FRAIL Scale Tool. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with practice staff and stakeholders to understand the implementation outcomes and barriers and enablers to implementation. Research was undertaken with appropriate informed consent of participants.

Recruitment

The research team partnered with two Primary Health Networks (PHNs) – Sydney North Health Network (SNHN) and Brisbane South (BSPHN) – to recruit 19 general practices (12 in SNHN and seven in BSPHN). PHNs are not-for-profit organisations funded by the Australian Government to improve access to primary care services for patients, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes, and improve coordination of care. The SNHN region is predominantly metropolitan and is ranked the least socioeconomically disadvantaged PHN in Australia. Comparatively, BSPHN is a diverse region, including metropolitan, rural and remote island locations, and has the largest urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population compared to all other metropolitan PHNs nationally (2.8% of residents). There are 292 general practices in SNHN and 339 in BSPHN, and 17.1% of SNHN residents (Sydney North Health Network 2023) and 13.6% in BSPHN are aged ≥65 years (Brisbane South Primary Health Network 2023).

Practices were recruited between April 2021 and June 2023, via a PHN practice newsletter, expressions of interest and PHN/researcher practice networks. Practices were eligible to participate if they had electronic practice management software and were comfortable to share data within the approved ethics protocol.

Tool development and implementation

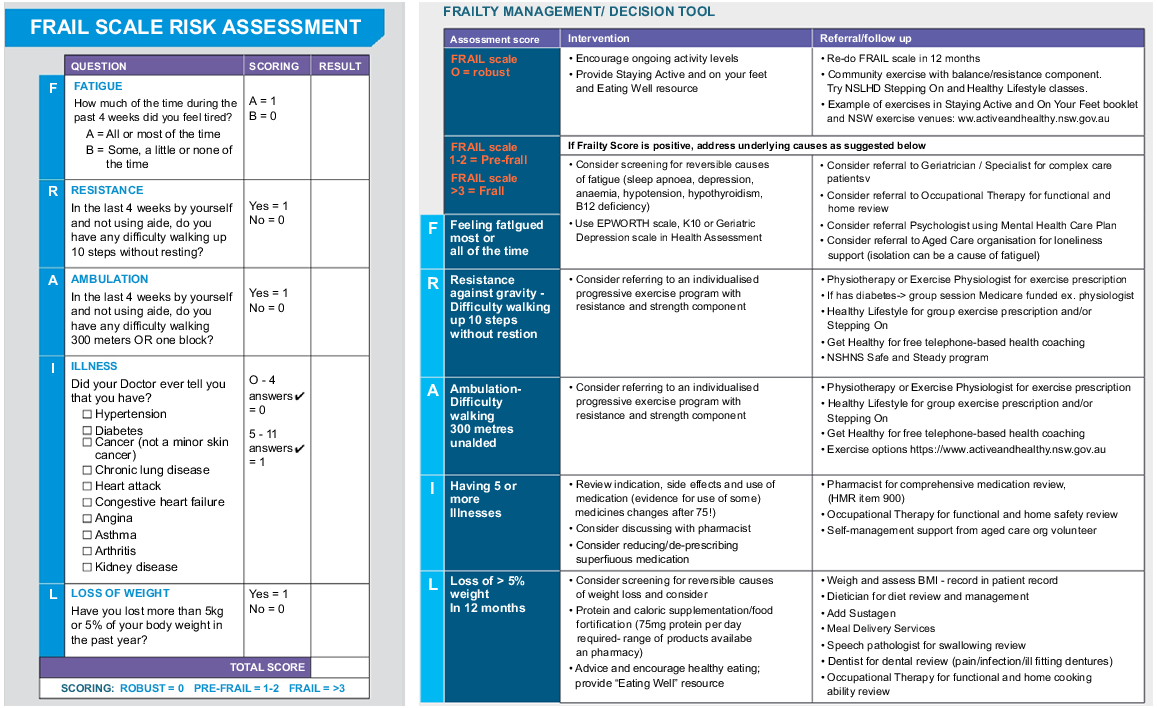

The FRAIL Scale Tool, adapted by SNHN, Northern Sydney Local Health District and Pen CS (Topbar), was built into the general practice clinical support system (Topbar), and integrated with general practice software (Medical Director, Best Practice and Zen Med). The frailty score was recorded by the Tool and practices referred to the associated management suggestions and interventions recommended within the Tool (Fig. 1). Practice staff could print the results of the questionnaire, save it to the patient record or view a patient’s Frail Score history.

Each study practice installed the FRAIL Scale Tool and screened consenting patients aged ≥75 years for risk of frailty. Patient selection was bespoke to each PHN, with practices in the SNHN screening patients at the time of the 75+ HA or opportunistically (e.g. with blood pressure checks or dressings), whereas those in the BSPHN screened eligible patients at the time of completing the 75+ HA. The PHNs had financial support in place with participating practices to cover practice staff time for data collection (AU$50 per patient screen for up to 100 patients per general practice).

Training for the practices included: (1) an in-person workshop outlining the aims of the study, how to complete data collection and use the FRAIL Scale Tool; and (2) check in visit/s, or phone or video calls, and emails with the project sponsor or researcher. Implementation of the Tool commenced in September 2021 and data collection was completed in June 2023.

Measures

Data collection

Practice staff conducted FRAIL Scale screening with patients aged ≥75 years and collected de-identified data on a spreadsheet provided by the research team including: date of the 75+ HA, patient; date of birth, gender and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander background; whether the patient had been hospitalised in the previous 12 months; current medication number; and patient FRAIL Scale Tool results and scores; suggested management/referral options; and any barriers identified by patients or carers for accessing suggested management/referral options.

Practice population data were provided by the PHNs, and practices provided data on the total number of GPs and nurses working in the practice. Practices were classified on location (i.e. metropolitan or regional) using the Modified Monash Model (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2023).

All staff conducting the FRAIL Scale Tool assessments were invited to be interviewed. Invitations were emailed to participants, with information describing the rationale for the research provided via an information sheet. All participants were required to give informed, written consent to participate and were sent the interview questions in advance, allowing them time to consider their viewpoints. Interviews were conducted between March 2022 and May 2023.

Interviews were semi-structured and informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al. 2009). The relevance of each CFIR determinant to implementation of the FRAIL Scale Tool was rated on a five-point Likert scale by the research team members (CN, JJ, DC), and those with the highest rating (mean of two or more) were used to determine interview questions (Haverhals et al. 2015). Interview questions (Supplementary File S1) were developed using the Interview Guide Tool available via the CFIR website (https://cfirguide.org/). All interviews were conducted via telephone by a researcher with extensive experience in qualitative research (JJ). Interviews continued until data saturation occurred and no new ideas were identified in responses. The interviewer recorded notes during and after interviews to identify barriers and enablers to implementation (JJ). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim using Otter Artificial Intelligence (https://otter.ai/), cross-checked against the recording (JJ), and anonymised.

Qualitative interview analysis

Interview transcripts were coded, using a deductive process guided by Proctor’s (Proctor et al. 2011) feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of implementation outcomes and CFIR, to understand barriers and enablers to implementation with a view to guiding ongoing implementation (Hamilton and Finley 2019). These notes were reviewed, discussed and refined with a second researcher (BL), who had read and coded a pragmatically selected subset of transcripts independently. Team agreement was sought as the determinants were reviewed, refined and reordered. Nvivo12 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) was used to support the analysis.

Results

Characteristics for the 19 practices that implemented the FRAIL Scale are outlined in Table 1. All practices were located in metropolitan areas except one BSPHN regional practice (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2023).

| FRAIL scale implementation practices – mean (s.d.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 19)A | SNHN (n = 12) | BSPHN (n = 7) | ||

| Practice population | 5013.1 (2680.8) | 3715.6 (2196.0) | 7051.9 (2095.2) | |

| Number of active patients aged ≥75 yearsB | 321.9 (284.1) | 183.4 (120.2) | 539.6 (337.9) | |

| Number of GPs in the practice | 6.6 (2.7) | 4.5 (3.8) | 9.9 (5.4) | |

| Number of nurses in the practice | 2.7 (2.1) | 1.6 (0.7) | 4.7 (2.2) | |

Patients screened for risk of frailty were an average age of 82.6 years (s.d. 5.8) and 0.6% identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (BSPHN n = 4; SNHN n = 0). The average FRAIL Scale score was 1.9 (Table 2), with 20% (n = 211) of patients assessed as robust (frail score = 0), 47% (n = 508) as pre-frail (frail score = 1–2) and 33% (n = 352) as frail (frail score = 3–5) (Table 3). Overall, 80% (n = 860) of patients met the criterion for frailty/pre-frailty, with 84% (n = 617) of patients in the SNHN assessed as being frail/pre-frail and 71% (n = 243) in the BSPHN likewise being assessed.

| Frail scale screens – number (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 1071) | SNHN (n = 728) | BSPHN (n = 343) | ||

| Robust (frail score = 0) | 211 (20) | 111 (15) | 100 (29) | |

| Pre-frail (frail score = 1–2) | 508 (47) | 337 (46) | 171 (50) | |

| Frail (frail score = 3–5) | 352 (33) | 280 (38) | 72 (21) | |

| Hospitalised in the last 12 monthsA | 47 (8.2) | 11 (4.7) | 36 (10.6) | |

The key resources identified to support risk of frailty were: (1) exercise interventions (classes, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists); (2) medication reviews (pharmacy and GP); (3) referrals to geriatricians; and (4) nutrition support. Primary barriers that patients and their carers identified to accessing the management options were: (1) cognitive decline; (2) mobility, transport and access issues; (3) cost; and (4) issues related to COVID-19 isolation and lockdowns.

Qualitative interviews

Interviews were conducted with 14 practice staff (PS) who had used the Tool (11 practice nurses, one chronic disease manager/accredited practicing dietitian, one GP, one pharmacist) and the SNHN aged care lead. Participants were all female; nine from the SNHN and five from the BSPHN. Interviews lasted between 13 and 63 min (mean 21 min).

Feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of the FRAlL Scale Tool

Feedback from staff highlighted three key themes: the Tool (1) was easy to use; (2) formalised assessment for risk of frailty; and (3) was patient-focussed.

Practice staff found the Tool was a concise (takes 2 minutes), user friendly, intuitive method to assess for risk of frailty with minimal training required to use the Tool. Staff appreciated the specific questions in the Tool that were unlike the broader questions in the 75+ HA.

In terms of usability in the practice, I think it’s quite easy. (PS-06)

Some staff reported that patients from non-English speaking backgrounds found the FRAIL Scale questions easier to understand than those in the 75+ HA while recognising that there is a requirement for providing the Tool in languages other than English.

There was recognition that assessing for risk of frailty was not currently routine practice and practice staff appreciated involvement in the research program as a quality improvement project.

Prior to having the formal app, it was almost a little bit ad hoc. (PS-04)

Staff reported that it was easy for patients to understand the link between the FRAIL scale score and the management recommendations made with the screening tool. The Tool was:

A great way for patients to see their score, and then see the recommendations, gives a very holistic view as to what they should be doing. (PS-02)

It enables us to have something tangible that we can then use to recommend other services. (PS-05)

Staff reported that patients understood that being assessed for risk of frailty was proactive and they could see the reason for repeating the FRAIL Scale screen after a few months to see if there was a change in the FRAIL Scale score as a result of intervention/s.

Facilitators

Staff conducting risk of frailty screening identified methods to make it ‘business as usual’.

Key facilitators identified by practice staff to using the FRAIL Scale tool were: (1) incorporating the FRAIL Scale Tool and management options into the 75+ HA template; (2) screening for risk of frailty opportunistically; and (3) providing support for patients to access risk of frailty management resources and interventions.

(1) Incorporating the Tool into the 75+ HA templates linked risk of frailty screening with existing funding

The Tool was easy to incorporate into workflows with the 75+ HA, which funded the nurse time to complete the assessment.

It certainly complements the completeness of the health assessment. (PS-04)

During implementation of the Tool, some staff incorporated the FRAIL Scale tool, including the management recommendations, into their 75+ HA practice software templates. They felt that frailty screening early in the 75+ HA was an effective method of addressing the mobility and nutrition sections of the 75+ HA.

It triggers us to actually ask those questions, and we’ve also added the recommendations underneath in red so we can talk about that with the patient right then. So, I think that’s been a lot easier to implement it when it’s actually on the template when we talk to the patients. (PS-11)

Practice staff could see the benefits of introducing the Tool for screening younger patients before they became frail or opportunistically while seeing patients for other reasons such as blood pressure checks, dressings or mental state examinations.

Some practice staff felt that providing external patient support for accessing and navigating management resources would reduce the burden on busy practice staff.

I’ve probably been here for about a year now. In that sense, it’s sometimes hard to know what services would be good for that patient, or what they kind of need. So yeah, I think just some more information on those services would be good. (PS-02)

Barriers

Key barriers to implementation within the practice were: (1) the challenge of encouraging some patients to access the referral and management options; (2) the lack of an item number to fund GPs to screen for frailty; (3) COVID-19 pandemic; and (4) access to the Tool.

Practice staff were often frustrated at the lack of patient motivation to take up frailty management recommendations and the patient’s ability to access management resources due to cost and travel requirements.

A lot of the elderly don’t drive…don’t have access to the internet or don’t know how to use a computer, I think it would be better if we have someone who can give them a call. (PS-10)

GPs do not have an item number and therefore funding for assessing risk of frailty, and were not routinely using the Tool. In addition, GPs have limited time available for each patient consult:

When an elderly patient walks in you’ve already got this…and that, it’s very time consuming…I’m stretched enough as it is. So that’s why the nurses who are paid by the practice, it works well them doing it. (PS-09)

Practice nurses, whose time was Medicare funded to complete the FRAIL scale in conjunction with the 75+ HA, appreciated the Tool and were very engaged with the research. They recognised that GP time is limited:

…it can feel like there’s a lot to do and there’s not enough time…the doctors have a lot on their plate, in terms of what they’re already screening and assessing. So it’s easier for us as nurses to do…it for them. (PS-02)

Knowledge of services and resources available in the community to manage risk of frailty was identified as a challenge for some practice staff.

It’s sometimes hard to know what services would be good for that patient, or what they kind of need…I think just.more information on those services would be good. (PS-03)

During COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, risk of frailty screening was reduced due to other practice priorities such as vaccinations and patients not attending the practice for yearly 75+ HA.

In addition, as the Tool was linked with the Topbar clinical decision support system, it was not always available on all computers in the practice. The PHNs have now switched to an alternative clinical support system, so Topbar will no longer be in use for the practices involved. Sitting the screening tool within practice software or the 75+ HA was seen as a solution to this issue.

Discussion

Our study suggests a significant prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty in patients aged ≥75 years attending Australian general practice, and practice willingness and ability to institute frailty screening in this cohort. Although a systematic approach to identifying risk of frailty is currently lacking in general practice in Australia, the annual Medicare-funded 75+ HA, conducted with more than 600,000 older Australians annually (Mitchell and D’Amore 2021), provides an excellent vehicle to include such an approach. Criteria for inclusion in the assessment, set by the Department of Health and Aged Care for Medicare compliance, require assessment of falls risk, vision, hearing, current weight and cognitive assessment, but not risk of frailty. Including screening for risk of frailty with the 75+ HA in our study was found to fit with practice workflows and met practice and patient acceptability, as well as quality and efficiency requirements. Additionally, incorporating the FRAIL scale into the annual 75+ HA, by updating best practice into these Medicare-funded assessments, offers an ideal opportunity to link those at risk of frailty with management resources and interventions to reduce progression and potentially reverse decline (Travers et al. 2019) (Supplementary File S2: 75+ HA_optimised). The 80% prevalence of pre-frail and frail patients in our patient population highlights the opportunity presented by the general practice setting for early detection, assessment and management of risk of frailty in Australian communities.

In addition to incorporating the FRAIL Scale Tool in the 75+ HA templates, practice staff identified other key strategies to support broader implementation. Incorporating the FRAIL Scale Tool into the practice software would enable practices to generate reports on frailty screening, track changes and improve GP access to the results. Additionally, linking risk of frailty screening with other appropriate government (Medicare)-funded item numbers would enable screening to be introduced for other groups of non-age-related, at-risk patients.

Risk of frailty management resources and services are required to support implementation. Practice nurses recognised that patients may be more amenable to risk of frailty management recommendations coming from the GP. In addition, resource options are required in multiple formats that are easily accessible for practice staff and patients, along with community support for patients to access risk of frailty management options. Linking in allied health professionals with a special interest in frailty would facilitate referral pathways.

Limitations

Data collection for this study was conducted in a small cohort from only two predominantly metropolitan regions of Australia and the results may not be generalisable to rural and remote regions. Further, higher rates (84%) of frail/pre-frail patients seen in the SNHN compared to the BSPHN (71%) likely reflect opportunistic screening in Sydney North compared with the more structured approach via the 75+ HA in Brisbane South. Despite the difference, the prevalence of frailty and prefrailty in patients aged ≥75 years in all practices using the Tool was high. As frailty screening in this pilot study was predominantly conducted by practice nurses, the majority of the qualitative data came from interviews with nurses, and only one GP implemented and was interviewed regarding implementation of the tool.

Future research

Research is ongoing within the partnership between Centre for Health System Reform and Integration, Sydney North PHN and Brisbane South PHN to understand the types of resources and management options that are required and are available in the community to support identified need, and the acceptability of the frailty risk assessment and management approach to a broader cohort of patients, carers and general practice staff. This will include work with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and the Australian Association of Practice Management to include the frail scale in general practice processes for ongoing frailty detection and intervention within the primary care sector.

Conclusion and recommendation

General practice represents the entry point into the healthcare system for many older adults who may be becoming pre-frail or frail. Incorporating frailty screening into the annual 75+ HA fits with the practice workflow and offers an ideal opportunity to intervene early in the ageing process. Effective screening in the primary care setting will facilitate early identification of risk of frailty and allow ongoing management with appropriate evidence-based preventative and rehabilitation actions to reverse or reduce frailty risk.

Data availability

The datasets analysed for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of funding

This research has been funded through the Centre for Health System Reform and Integration (CHSRI), University of Queensland-Mater Research Institute (UQ-MRI), Northern Sydney Primary Health Network trading as Sydney North Health Network (SNHN) and Brisbane South Primary Health Network (BSPHN).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the partner organisations: the Northern Sydney Primary Health Network trading as Sydney North Health Network (SNHN) and Brisbane South Primary Health Network (BSPHN) and the general practices who conducted the data collection. Dr Breanna Lepre was second coder on the qualitative transcripts.

References

Abbasi M, Khera S, Dabravolskaj J, Garrison M, King S (2019) Identification of frailty in primary care: feasibility and acceptability of recommended case finding tools within a primary care integrated seniors’ program. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 5, 2333721419848153.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (2014) Health assessment for people aged 75 years and older. Available at https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mbsprimarycare_mbsitem_75andolder [Accessed 12 September 2023]

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Health Workforce Locator. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/resources/apps-and-tools/health-workforce-locator/app [Accessed 12 September 2023]

Bandeen-Roche K, Seplaki CL, Huang J, Buta B, Kalyani RR, Varadhan R, Xue QL, Walston JD, Kasper JD (2015) Frailty in older adults: a nationally representative profile in the United States. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 70, 1427-1434.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Boreskie KF, Hay JL, Boreskie PE, Arora RC, Duhamel TA (2022) Frailty-aware care: giving value to frailty assessment across different healthcare settings. BMC Geriatrics 22, 13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brisbane South Primary Health Network (2023) Our region. Available at https://bsphn.org.au/about/our-region/ [Accessed 12 September 2023]

Cameron ID, Fairhall N, Langron C, Lockwood K, Monaghan N, Aggar C, Sherrington C, Lord SR, Kurrle SE (2013) A multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention reduces frailty in older people: randomized trial. BMC Medicine 11, 65.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC (2009) Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4, 50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dent E, Lien C, Lim WS, Wong WC, Wong CH, Ng TP, Woo J, Dong B, de la Vega S, Hua Poi PJ, Kamaruzzaman SBB, Won C, Chen LK, Rockwood K, Arai H, Rodriguez-Mañas L, Cao L, Cesari M, Chan P, Leung E, Landi F, Fried LP, Morley JE, Vellas B, Flicker L (2017) The Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines for the management of frailty. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 18, 564-575.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 56, M146-M157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gardiner PA, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ (2015) Validity and responsiveness of the FRAIL scale in a longitudinal cohort study of older Australian women. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 16, 781-783.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hamilton AB, Finley EP (2019) Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Research 280, 112516.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Haverhals LM, Sayre G, Helfrich CD, Battaglia C, Aron D, Stevenson LD, Kirsh S, Ho M, Lowery J (2015) E-consult implementation: lessons learned using consolidated framework for implementation research. American Journal of Managed Care 21, e640-e647.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP (2019) Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. The Lancet 394, 1365-1375.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Job J, Clark D, Arapova J, Nicholson C (2023, 17–18 August 2023) Paper presented at Abstracts of the Australasian Association for Academic Primary Care (AAAPC) Annual Research Conference Australian Journal of Primary Health 29, xxxvii.

| Crossref |

Mitchell EKL, D’Amore A (2021) Recent trends in health assessments for older Australians. Australian Journal of Primary Health 27, 208-214.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK (2012) A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 16, 601-608.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56/chapter/Recommendations [Accessed 12 September 2023]

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M (2011) Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 38, 65-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sydney North Health Network (2023) About Sydney North Health Network. Available at https://sydneynorthhealthnetwork.org.au/about-us/our-region/ [Accessed 12 September 2023]

Thompson MQ, Theou O, Karnon J, Adams RJ, Visvanathan R (2018) Frailty prevalence in Australia: findings from four pooled Australian cohort studies. Australasian Journal on Ageing 37, 155-158.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thompson MQ, Theou O, Tucker GR, Adams RJ, Visvanathan R (2020) FRAIL scale: Predictive validity and diagnostic test accuracy. Australasian Journal on Ageing 39, e529-e536.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, Cooney MT (2019) Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. British Journal of General Practice 69, e61-e69.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |