Leading primary care under the weight of COVID-19: how leadership was enacted in six australian general practices during 2020

Kathleen Wisbey A , Riki Lane

A , Riki Lane  A , Jennifer Neil A , Jenny Advocat

A , Jennifer Neil A , Jenny Advocat  B , Karyn Alexander A , Benjamin F. Crabtree

B , Karyn Alexander A , Benjamin F. Crabtree  C , William L. Miller D and Grant Russell

C , William L. Miller D and Grant Russell  A *

A *

A

B

C

D

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged health care delivery globally, providing unique challenges to primary care. Australia’s primary healthcare system (primarily general practices) was integral to the response. COVID-19 tested the ability of primary health care to respond to the greater urgency and magnitude than previous pandemics. Early reflections highlighted the critical role of leaders in helping organisations negotiate the pandemic’s consequences. This study explores how general practice leadership was enacted during 2020, highlighting how leadership attributes were implemented to support practice teams.

We performed secondary analysis on data from a participatory prospective qualitative case study involving six general practices in Melbourne, Victoria, between April 2020 and February 2021. The initial coding template based on Miller et al.’s relationship-centred model informed a reflexive thematic approach to data re-analysis, focused on leadership. Our interpretation was informed by Crabtree et al.’s leadership model.

All practices realigned clinical and organisational routines in the early months of the pandemic – hierarchical leadership styles often allowing rapid early responses. Yet power imbalances and exclusive communication channels at times left practice members feeling isolated. Positive team morale and interdisciplinary teamwork influenced practices’ ability to foster emergent leaders. However, emergence of leaders generally represented an inherent ‘need’ for authoritative figures in the crisis, rather than deliberate fostering of leadership.

This study demonstrates the importance of collaborative leadership during crises while highlighting areas for better preparedness. Promoting interdisciplinary communication and implementing formal leadership training in crisis management in the general practice setting is crucial for future pandemics.

Keywords: community health care, delivery of health care, delivery of health care: integrated, health care disparities, organisation: culture, patient care: management, patient care: team, patient-centred care, physicians’ practice patterns, primary health care.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly impacted the global delivery of health care (Verhoeven et al. 2020). Although Australia experienced relatively low COVID-19 related mortality during 2020, two-thirds of COVID-19 cases and nearly 90% of deaths were in metropolitan Melbourne (Braithwaite et al. 2021). During this time, the State Government responded by imposing one of the world’s harshest ‘lockdowns’, enforcing restrictions on physical contact, social interaction and leaving home (Boroujeni et al. 2021). These restrictions saw wider implications for health care delivery, particularly primary care practices’ efforts to support the overall pandemic response.

Australia’s primary care system, primarily delivered from private general practices, faced unforeseen impacts of the pandemic, including significant disruption to both logistical and organisational operations. Coupled with government mandated physical distancing restrictions, practices needed to undertake major innovations to ensure staff safety and continuity of patient care (Kippen et al. 2020).

Transforming primary care practices is a complex process. Evaluation of primary care practice responses to prior pandemics demonstrates varied practice approaches and levels of involvement, but generally a non-optimal level of preparedness (Desborough et al. 2021). Leadership is seen as a critical factor for successful primary care transformation (Donahue et al. 2013), and may well be important in a practice’s ability to negotiate the challenges of a pandemic. Previous studies have highlighted the presence of hierarchical leadership structures in primary care (Finlayson et al. 2009; McInnes et al. 2015), which has potential to impact on their responsiveness.

Crabtree et al. (2020) reviewed existing complexity science literature and identified nine leadership attributes hypothesised to support primary care practice change (see Table 1). They saw these attributes as being a critical resource for change within the dynamic systems that characterise primary care practices. They defined leaders as ‘those individuals who (1) hold formal or legitimate leadership titles or positions within the organisation, and (2) have financial control (financial power) over the practice’. They defined leadership as the ‘enactment of actions, behaviours, or attitudes that influence the policies and procedures, mission and vision, and process tools (such as communications and information sharing) that shape the direction of the organisation’ (Crabtree et al. 2020).

| Attribute 1 | Leaders motivating others to engage in change | Leadership engages workforce when system change occurs or needs to occur, and provides motivation and encouragement to support system change efforts through external/extrinsic motivation (transactional leadership) and internal/intrinsic motivation (transformational leadership), while also overcoming resistance. Although a transactional style can be effective in some contexts, it is recognised to not be ideal in innovative and rapidly changing contexts | |

| Attribute 2 *Collapsed attribute | Managing power and assuring psychological safety | Power – Leadership addresses issues of power and social influence within and among the workforce, including issues like bullying, freeloading and cheating, and seeks mutual respect and fairness across hierarchy | |

| Psychological safety – Leadership assures that the work environment is one in which everyone can express opinions or contribute to discussions without fear, such that practice members speak up with suggestions, questions and criticisms of work-related processes | |||

| Attribute 3 | Enhancing communication and information sharing | Leadership undertakes and manages the multiple forms of internal and external communication and information sharing related to the workplace. Communication occurs in various forms, from formal meetings to informal exchanges connecting people, and using both written and verbal information as appropriate | |

| Attribute 4 | Encouraging boundary spanning | Reaching across established borders to build relationships, gain information and resources, and form productive connections. Vertical boundary spanning that cuts across levels and hierarchy (e.g. physicians vs nurses), horizontal boundary spanning (e.g. across functions and expertise), and stakeholder boundary spanning (e.g. beyond the organisation to include the larger medical neighbourhood) | |

| Attribute 5 *Collapsed attribute | Generating collectivity and interconnectedness | Instilling a collective mind – Leadership attends to patterns of heedful interrelations whereby individuals recognise interconnectedness and co-create group cohesion and shared purpose. Team with a common understanding | |

| Cultivating teamwork: Leadership cultivates the work environment to nurture team or group formation, development, membership and effectiveness. This is different from collective mind in that cultivating teamwork is about how to get a group of people to effectively work on a set of tasks, whereas instilling a collective mind focuses on getting teams and individuals in a practice to have a common purpose and understanding | |||

| Attribute 6 | Fostering emergent leaders | Leadership fosters dynamic interaction within the workforce such that leadership by members emerges at times for problem solving or to resolve tension or other moments requiring leadership action | |

| Attribute 7 | Generating a learning organisation | Leadership helps to generate an organisation that is skilled at creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights |

Names and definitions adapted from Crabtree et al. (2020). Attributes 2 and 5 comprised two original attributes respectively.

Our earlier analysis (Russell et al. 2023) showed how the COVID-19 pandemic transformed these practices’ clinical and organisational routines. Findings pointed to leaders being key to shaping and implementing these changes. For this study, we did not have a specific hypothesis, but anticipated that variations in practice leadership would impact upon their response to the pandemic. We therefore examined the ways in which exemplary characteristics of leadership were identified in the practices, using the Crabtree model as a lens. We asked (1) how leadership was enacted in general practices during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, and (2) how were attributes of leadership implemented to support practice teams.

Methods

Study design

Our participatory prospective qualitative multiple case study design involved general practitioners (GPs; see Table 2 for abbreviations) as participant investigators. The case study methodology used a rapid ethnographic approach, where the practice is the case (Russell et al. 2012). The multiple case study approach allows a detailed, intensive exploration of individuals and organisations in context (Patton 2002), and the prospective structure allowed assessment of changes over time. Our methodology is detailed elsewhere (Russell et al. 2021). This secondary analysis investigating the role of practice leadership in the pandemic was informed by Crabtree et al.’s leadership model (Crabtree et al. 2020), which we saw as a valuable lens for data analysis, given its identification of leadership characteristics promoting change.

Setting and participants

The study was set in six general practices of varying size and organisational model in metropolitan Melbourne, Australia, between April 2020 and February 2021. Chief investigators contacted potential GP investigators from current academic staff or recent PhD graduates of the [university GP department], prioritising practices of varying size and organisational model. GP investigators then contacted the practice lead/owner or manager of the practices where they based their clinical work, and informed consent was obtained from all PO and participants. GP investigators recruited practice interview participants, including GPs, nurses, practice managers (PM) and administrative staff to participate in a series of semi-structured interviews (Russell et al. 2023).

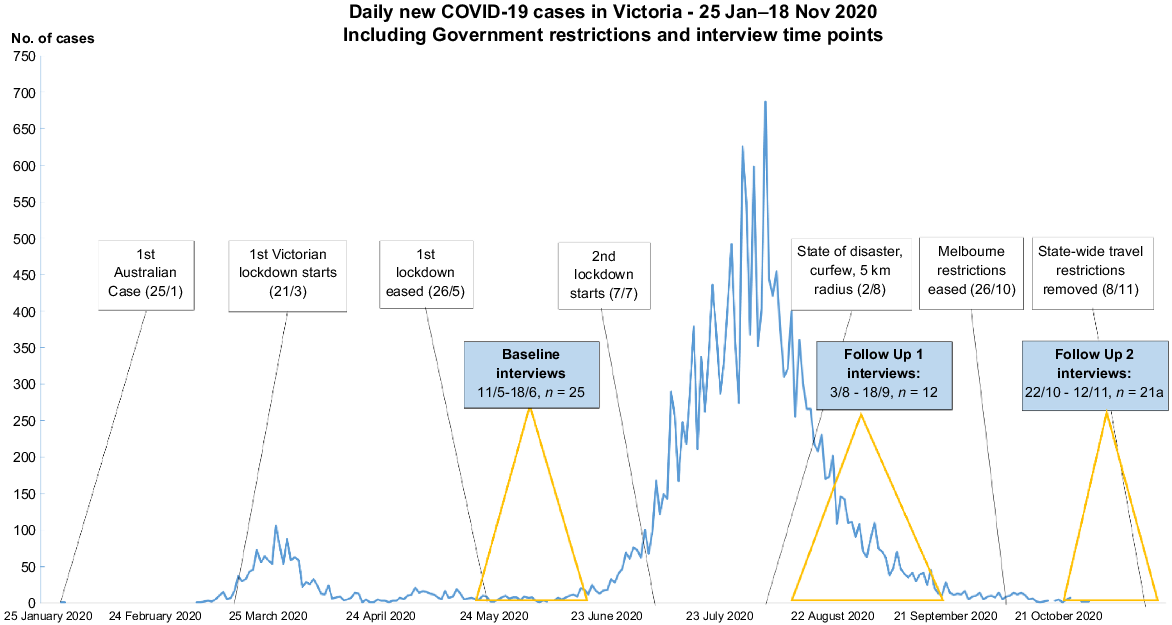

Data collection

Data were collected from multiple sources (see Table 3). The GP investigators completed structured diaries and a practice description tool (Balasubramanian et al. 2010; Lane et al. 2017), collected key practice documents, and photographed signage and layouts. The PhD level social scientists (JA and RL) conducted semi-structured, in-depth telephone or videoconference interviews with clinical (GPs and practice nurses) and administrative staff in three time periods between May and November 2020 (see Fig. 1 and Table 3), and reflective interviews with GP investigators in January 2021. Interviews focused upon participants’ individual experiences, perceived practice responses, and factors influencing practice performance and leadership during the first year of the pandemic. Member checking was achieved by presenting and seeking feedback on emerging findings through a video presentation to practices; responses informed analysis.

| Source | Details | Timing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practice description tool | Key observational and demographic data for each site. Clinician investigators made initial entries at baseline and updated with ongoing collated information | May–June 2020 followed by updates | |

| Investigator diaries | Investigators collected notes of working in general practice during the pandemic: focused on generating contemporaneous records of their experience | May to November 2020 | |

| Document analysis | Practice policies and information sheets outlining pandemic management, including practice’s prior emergency response plan, government required plans for mitigating COVID-19, and templates or scripts for communication with patients and community members | May–June 2020 followed by updates | |

| Interviews with clinicians, staff | Non-participant researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with recruited practice staff | Three time points: May–June, August–September; October–November | |

| Photographs | We collected digital photographs of relevant practice signage, leaflets, the layout of practice waiting rooms, reception areas and other relevant material | May–June 2020 followed by updates | |

| Presentations of findings to practices | Practices received a mid-project overview report of findings across practices. Late in data analysis, we shared emergent findings through electronic presentations of summarised practice findings. using a member checking procedure around any uncertainty in data interpretation. Responses to the presentation informed the final analysis | August 2020 report December 2020 online presentations of findings | |

| Participant investigator interviews | Each clinician investigator was interviewed late in data collection: questions explored emerging findings and clarified areas of uncertainty. Interviews focussed on participant’s individual pandemic experience, responses from the practices, and thoughts on factors influencing the practice’s performance | January 2021 |

Data management

All digital data were stored on a secure server. Interviews were professionally transcribed and all identifying information removed. Interview transcripts and observational data (diaries and practice documents) were coded using NVivo12 (QSR International Pty Ltd 2018).

Data analysis

Our initial coding template was based on emerging data themes and frameworks of complexity (Plsek and Wilson 2001), routines (Becker 2004) and relationships: drawing on Miller et al.’s relationship-centred model of primary care practice development (Miller et al. 2010), and prior approaches to investigating primary care practice routines (Russell et al. 2012; Lane et al. 2017). Miller et al.’s model identified key features of practices that successfully underwent change: practice core, adaptive reserve and the local landscape. Thus, it provides a good model for looking at how practices responded to COVID.

For this paper’s leadership focus, we used a reflexive thematic analysis approach to re-analyse the principal data set (Braun and Clarke 2006). In line with the primary study’s methodology, our unit of case analysis was the practice, not the individual clinicians. We deployed an a priori template coding approach (King 2012) informed by Crabtree et al.’s model of leadership attributes (Crabtree et al. 2020). That a priori framework (Gale et al. 2013) was modified in light of early analysis of the study data relevant to leadership. Initially, KW modified the coding tree, which was discussed and agreed upon by investigators. Crabtree’s model includes nine leadership attributes hypothesised to support change in family practice. Given that Crabtree saw the attributes as overlapping, and that our analysis plan was generated post- hoc, we chose to combine four attributes into two, with seven remaining themes (Table 1). These attributes guided secondary data analysis, through introducing new NVivo subcodes used to further explore ‘Leadership’, agreed upon at investigator meetings.

KW and JH collaboratively re-coded six clinician investigator (CI) interviews to this set of codes, with new codes inductively added. KW revisited initial codes with relevance to leadership, and re-coded against the attribute framework. The themes and sub-categories were iteratively discussed in investigator meetings. All research team members met on multiple occasions to discuss coding, emergent themes and interpretation of how leadership was enacted in practices during the pandemic.

Reflexivity

For the main study, investigators comprised four clinician educators, two clinician researchers, and two social science research fellows with PhDs and experience in qualitative research. Each was affiliated with a University Department of General Practice. This secondary analysis was performed by GR, JN and RL (participants in the main study (Russell et al. 2023)), and two medical students KW and JH – who were mentored as qualitative research assistants during a 2-month summer scholarship. Original investigators provided input into the research question, analysis and interpretation through regular meetings where data was summarised, presented explored and challenged. We completed Tong et al.’s consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al. 2007). Ethics approval was provided by [a university Human Research Ethics Committee].

Findings

The original study recruited six of eight general practices approached. Practices included a state-funded community health centre, a practice in a large corporate network, and four private practices of varying size, organisational structure, billing practices and patient demographics. We conducted 58 interviews with 26 practice staff, including five PO, five PMs, eight GPs (three were also POs), five reception staff (R) and six practice nurses. In addition, six reflexive interviews were conducted with GP clinician investigators at the end of data collection. Data saturation was achieved at each practice and across the sample, through the iterative cycles of data collection and feedback. Table 4 summarises practice characteristics, showing wide variation in leadership styles.

| Practice ID | Types of practice | Organisational structure | Leadership style | Meeting routines | Communication tools | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre COVID-19 | Post ‘1st COVID-19 wave’ | ||||||

| CHC | Community Health Centre | Board with a CEO | Collaborative | Monthly/as required-all staff | Weekly Zoom. Open to all staff, most attend | Set up WhatsApp group at start of COVID-19 (for general staff communication). Weekly CEO updates and email newsletters throughout the pandemic | |

| Increased attendance from pre-pandemic | |||||||

| SE1 | Private General Practice | Two principal GPs who own and run the practice | Practice owners: Hesitant leaders that adapted throughout the pandemic | GPs every 2 to 3 months, decided by principal GPs | Weekly Zoom meetings – only GPs. PM, nurses and reception not included in these meetings (met separately) | WhatsApp group for GPs at start of COVID-19 | |

| E | Private General Practice | Two principal GPs who own and run the practice | Practice owner decides | Every 1 or 2 months | Fortnightly zoom; nurses and receptionists rarely included. Peak of 2nd wave; no meetings – leadership made all decisions | Main GP communication through clinical meetings, supplemented by emails. Communication between nurses and reception via daily email updates. No utilisation of other channels; WhatsApp etc | |

| CBD | Private General Practice | Practice owner (also GP) | Practice owner decides | Monthly | Daily informal meetings amongst GPs | GP-only WhatsApp group prior to COVID-19, but used more often during pandemic. Separate GP and reception WhatsApp groups. Communication with nurses mainly by email. WeChat group added | |

| Weekly meetings ± Nurses | |||||||

| SE2 | Private General Practice within large corporate | Regional management oversee practice | Distant corporate leaders with appointed local leadership team | No all-staff meetings – off site managers only. No GP meetings and reception and nursing meet separately | Regular meetings between PM, head nurse and medical director | Medical director set up WhatsApp group for GPs. Reception had their own WhatsApp group also – used as main source of communication and information sharing | |

| W | General Practice and Health Hub | 8 GP part owners Director of larger health hub is also a partner owner of the GP (dual role). Total of 8 partners | Board of directors | Partners meet 1–2 times a month, GPs monthly lunch meeting, AGM | No practice wide meetings since early first wave – reported due to increased clinical demand with opening of respiratory clinic | WhatsApp group; GPs, some nurses and several managerial staff, used to post daily update. Delegated nurse and GP inactive during COVID-19 | |

Our analysis, based on exhaustive comparison of collected data, found that leadership structures and approaches varied across practices and changed over time. Among the four GP-owned practices, practices E and CBD had dominant leaders who were key decision-makers, whereas SE1 had hesitant leaders who became more collaborative. W was larger and a board of directors made decisions, delegating to leads. At SE2, a local leadership team (PM, nurse and medical lead) evolved early in the pandemic, but its agency was restricted by the remote corporate leadership. The CHC had the most collaborative approach, with input from all disciplines and the broader organisation.

Our findings are arranged to represent each domain in our consolidated version of Crabtree et al.’s approach (Table 1). A matrix (Appendix 1) comparing all practices across these domains is available in supplementary materials.

Our data show variation in leaders’ ability to motivate and encourage workers to support necessary organisational change. Early responses emerged in varied ways within CHC, W, E and CBD. Decisive and early top-down decision-making at E and CBD motivated workers to some degree; whereas CHC and W were more collaborative. SE2 and SE1 leaders responded more slowly to the pandemic, yet over time, staff both demanded and assumed active leadership roles, motivating others. Board members in W transferred the role of primary decision-makers to individual team leaders ‘on the ground’, demonstrating the leaders’ ability to motivate others.

We’ve been, yeah, a lot more agile, a lot more focused on just making quick improvements to deal with … So I think that will change for the long term really. We’ve proven to ourselves that we can achieve some pretty massive things in a very quick timeframe, so why not keep that ball rolling? (W GP2)

By contrast, SE2’s leadership structure (key decisions made by remote corporate leadership) contributed to practice members feeling lost and unmotivated – this was partially alleviated by the creation of a local leadership group.

There has been a lack of clear leadership within the medical team. Indeed, there is a distinct lack of team spirit, leadership and cohesion within the organisation. (SE2 GP)

Across the range of management styles (unilateral to collaborative) all practices made changes to structures to motivate practice staff to participate in adapting to the pandemic. This highlights that early unilateral leadership styles were effective in implementing COVID-specific managerial/practice changes, but at the expense of wider team cohesiveness.

As is traditional in primary care, most practices had a hierarchical structure: PO being lead decision-makers, followed by lead PM and/or lead GPs, with nurses and administrative staff below (McInnes et al. 2015). This frequently contributed to experiences of power imbalance and lack of psychological safety. CHC and W’s more collaborative approach helped counteract this, whereas SE2 and SE1 became more balanced over time.

The GPs within SE1 challenged this traditional hierarchy, raising concerns early by writing a joint letter to PO on the practice’s approach to the pandemic. This informal leadership altered the POs’ approach, creating greater transparency and inclusion among GPs, through regular meetings where they could participate in decision-making. Interestingly, initially the dynamic continued to exclude non-GP members from collaboration, which reinforced GP dominance, leaving several cohorts feeling undervalued.

It would just be nice to be included in some of the decision-making. And everyone wants their voice heard, don’t they? (SE1 de-identified)

Although pre-pandemic, nurses within one practice experienced feelings of psychological safety, relationships with the GPs fractured during the pandemic. This was attributed to the PO/lead GP being the power centre, primarily engaging with GP clinicians in meetings and increasing GP collaboration at the expense of other staff members.

I think everyone should be doing what they are best at. And doctors are best at treating people and making these decisions, clinical decisions. This is [a] clinical problem. (de-identified PO)

Nurses at another practice expressed similar feelings, whereby privileging of communication between GPs reinforced the traditional leadership hierarchy.

It just makes me feel like – not a second-class citizen pretty much, but that doctors are the most important ones in his/her [PO] eyes, and the nurses – well, he/she just doesn’t think about it enough to have addressed my concerns in any way. So that’s frustrating. (de-identified practice nurse)

Although organisational hierarchy is generally critiqued for reducing mutual respect among the workforce (Rogers et al. 2020), data from the CHC showed that in times of urgent and unplanned change, their hierarchy (which was not GP-dominated) minimised power conflicts and feelings of vulnerability amongst staff.

This one is very different to a regular general practice in that we have the GPs working but you have the governing body across the top… And in the case of a pandemic… actually sometimes hierarchy is useful then because they can make rules that everyone else has to follow. (CHC CII)

These examples show the degree to which communication structures were intricately implicated in power hierarchies. Communication was strong within disciplines, but challenging or not emphasised between disciplines. Practices where leadership improved communication between disciplines saw less fracturing of relationships.

Across practices, leaders recognised the importance of communication through establishing new methods to address evolving needs. However, implementation was variable, and at times inconsistent.

To counter the isolation induced by COVID-19, most practice leaders increased the frequency of clinical meetings compared with pre-pandemic (see Table 4), which assisted communication, including the transfer of COVID-19 related information. Two larger practices, CHC and W, quickly implemented weekly all-staff ‘Zoom’ meetings. Smaller practices established regular meetings, primarily involving the PO and GPs. As aforementioned, action by contractor GPs in SE1 resulted in major changes in practice leadership.

A group of us GPs … not including the two principals, came together and drafted a letter to the practice principals saying that we were concerned about how some of our practices were falling down in terms of both our safety – and our staff safety and all that of our patients, and we were very keen to address them in a more formal way because we felt that what had been done so far wasn’t working very well. (SE1 GP1)

Reflecting their highly individualised status as contractors in a corporate structure, SE2’s GPs very infrequently met, and relied on local leadership updates for clinical direction. By contrast, nurses had regular meetings.

WhatsApp was utilised variably at five practices; some initially for ‘informal’ conversation, with progression to it being a primary means of delivering updated COVID-19 information, decision-making and supporting practice change. WhatsApp effectively enhanced communication within SE1. Similar to the clinical meetings, WhatsApp groups in some practices only included GPs, and not PMs, nurses and receptionists.

Email was heavily relied upon, with reception staff from E noting that early in the pandemic, the PO communicated changes to practice policies up to three times a day. Remote leaders at SE2 similarly utilised email to distribute information; however, by the time it reached the local level, the advice was often outdated.

Despite more frequent formal communication and virtual interaction, CHC GPs noted that the lack of ‘corridor conversation’ was not effectively replaced by WhatsApp, describing this as a ‘huge collegiate loss’. The switch from rich (face-to-face) to lean (email, memos, What’sApp) communication was only partially effective, even with regular all-staff online meetings. Although needed in this instance, multiple new communication channels at times led to over-saturation of information, often at the expense of effectiveness.

Boundary spanning has three aspects: vertical spanning across levels and hierarchy; horizontal spanning across functions and expertise; and stakeholder spanning to organisations outside the practice (Crabtree et al. 2020). The degree to which leaders exhibited this attribute was inconsistent. Utilisation of vertical spanning by leaders was minimal across all practices; there was significant horizontal spanning at CHC, CBD, SE2 and W; and only CHC and W implemented stakeholder spanning.

Receptionists’ needing to rapidly modify their traditional work routines was a common example across practices of leaders implementing horizontal boundary spanning. Introducing temperature scanners and triaging patients meant reception had to work clinical equipment and identify ‘at risk’ patients – examples of horizontal spanning as these were previously considered beyond traditional administrative roles.

W’s leadership demonstrated stakeholder spanning, through implementing a government- funded respiratory clinic and externally led infection control clinical training. They demonstrated effective horizontal spanning through recruitment of ‘health assistants’; people with nursing, paramedic, retail, hospitality or even aviation backgrounds, whose job security had been impacted by COVID-19. The CHC reached outside the boundaries of the practice in liaising with key stakeholders – the State Government – and employing local community members as peer workers to implement a COVID-19 clinic for people in a public housing tower and other high-risk housing. Dental clinic staff were redeployed to this critical COVID-19 programme.

Across the practices, certain disciplines (reception in particular) took on new roles demonstrating mainly horizontal spanning, whereas the remainder of the heightened workload remained within disciplines. This represents a collective demonstration that horizontal spanning supported practice change.

Most practice leaders recognised the value of cultivating teamwork and nurturing cohesion within the team. The pandemic, however, challenged leaders’ abilities to foster heedful interrelations and group formation between members, due to the imposed work-from-home restrictions and shift to telehealth consultations. In our sample, cohesion within smaller practices was observed to a greater degree than larger practices (other than in the CHC), although there were some tensions between PO and workers, as illustrated by the GP letter to the SE1 PO (above). The leaders of two larger practices (CHC, W) tried to address these challenges by facilitating a strong local leadership team. Similarly, but later in the pandemic and with less impact, SE2 established a local leadership team to complement its existing and distant corporate leadership approach.

Early clinical challenges preoccupied leaders, and varying approaches to intrapractice communication highlighted their efforts to foster collectivity. Which disciplines were invited to clinical meetings was a contributing factor to wider feelings of practice cohesion.

In the past … there’s been a little bit of lack of communication and a lack of cohesion, and I felt that maybe with this crisis, might bring us together … I think we’re agreeing more, … we’re all sort of on the same page, but there’s always going to be differences in opinions and differences in the way we think things should happen. (SE1 GP)

Notably, the desire for ongoing improvement in team building continued to be recognised;

So I think that’s definitely the biggest thing in that centre that needs to improve, is the team ethos amongst the doctors. They [central managers] probably need to be a bit incentivised and autonomous to do their own thing, and look at their local factors, and they need to build the team ethos to make sure that you can react as a team, sensibly and consistently. (SE2 CII)

Although practices infrequently met Crabtree’s definition of a ‘team with a collective mind’, workers at several practices (E, W, SE2, CHC) commented that they felt ‘closer as a team’ despite physical distancing, segregated lunch breaks and lack of social interaction.

[Emerging from pandemic] if anything, I think we have solidified and as a practice having been through that, I think everyone’s looked after each other and have got to the other side stronger from an interpersonal relationship point of view, yes. (W GP)

This theme is strongly related to theme 3, as the use of virtual communication media and meetings was important for building interconnectedness.

The pandemic motivated system change, providing opportunities for practice staff to take on new responsibilities. Mostly, the pandemic created the ‘need’ for workers to ‘step up’ as new leaders, with few instances of practice leaders fostering environments to support emergent leaders.

Several practices experienced leadership changes at the pandemic onset. The CHC PM left just before the pandemic, and very early on a nurse established a ‘COVID-19 response committee’, sourcing COVID-19 protocols. The CBD PM also left immediately prior to COVID-19, but by contrast, the PO eagerly took over this role with a specific ‘heroic’ perspective.

This is what we have been waiting for all of our lives. This is why we went to medicine. Yes, there is a risk, but we signed a contract when we entered medical school… (CBD PO)

Lack of local governance within SE2 placed a strain on the practice leadership team from early on. With the practice under early financial strain and no concrete plans from central leaders, one GP ‘agreed’ to step up into the clinical lead position, supporting the idea that leaders were ‘needed’ during this time, rather than ‘fostered’, as per Crabtree’s definition.

The transition of leadership from board members to local team leads at W was the main example of active fostering of emergent leaders.

A ‘learning organisation’ is one that is skilled at creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge, and modifying behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights (Crabtree et al. 2020). In the learning process, organisations make cognitive, interpersonal and organisational adjustments that allow new routines to be successfully implemented (Edmondson 2003; Crabtree et al. 2020). All practices felt that they had changed how they did their work; however, transformation only occasionally met Crabtree’s definition.

Interpersonal growth between W’s staff brought the practice team ‘closer together’, and resulted in foreseeable permanent changes to clinical routines and structures.

And then on the leadership sense … I think that will continue on. That’s my feeling. And I think we’ve just made a decision that maybe our previous world was that we were just too slow and why were we too slow and look at what we can achieve in a short period of time. (W GP1)

Emergent leadership demonstrated by contractor GPs at SE1 illustrates how leadership behaviours, from levels other than the top of a hierarchical arrangement, are essential to reinforce continual reflection and learning within an organisation. Members of SE1 reflected changes to how leaders did things assisted practice success during the pandemic.

Although some practices demonstrated behaviours that encouraged the development of their practice into a learning organisation, others focused on the clinical demands of the pandemic, as seen by E and CBD. Whereas infrequent reference was made to being a learning organisation at CBD, some staff members viewed the PO’s leadership style as successful.

I felt like she [PO] … was really driving quick changes as they needed to happen, because she was driven by not only her clinical skills and her clinical knowledge about PPE [personal protective equipment] and infection, but she was also driven by the fact that she’s got a stake in the company, in the practice. (CBD CII)

Overall, practices were able to partially move towards being learning organisations – principally through rapid adaptation to emerging data and COVID-19 updates. This highlights that contributions from levels other than the top of the hierarchy are vital to organisational success, and that interpersonal growth strengthens changes.

Discussion

The pandemic provided a unique opportunity to explore practice leadership styles and assess readiness to respond to crisis. Our main outcome paper highlighted the extent to which practices realigned their organisational and clinical routines as a consequence of the pandemic. In this paper, Crabtree’s leadership framework helped us uncover fundamental elements of how practice leaders supported system change at a time of profound strain on healthcare systems. Modifications to care delivery were widespread, and our analysis emphasised the importance of leadership to key practice responses to the pandemic. However, leaders varied in their effectiveness, creativity and ability to motivate, while the absence of leadership (as in SE2) was challenging to the practice team. Leaders found it difficult to span boundaries within or beyond the practices, and generally operated within pre-pandemic hierarchies.

All practices experienced challenges, with contrasts. Four practices were able to adapt quickly; E and CBD – the smaller practices, exemplified the effectiveness of dominant leaders early in the crisis, whereas two larger practices (CHC and W) did this through a more collaborative model, with positive impacts on team morale. SE1 and SE2 responded more slowly, requiring emergent local leadership groups to push adaptation. Although our data resonated with components of the model, we were struck by how practices struggled with issues of power, psychological safety and facilitating effective communication. Few managed to help leaders emerge.

Managing power and hierarchical leadership

Healthcare systems are complex, inherently political structures (Rogers et al. 2020). Traditional hierarchical power structures within primary care impact physician leadership and decision-making processes (Finlayson et al. 2009; McInnes et al. 2015). Variants of these were present at all practices in our sample, which frequently contributed to members feeling undervalued and excluded from decision-making. Prior research suggests that the ‘position’ of a discipline within a team hierarchy influences how a member’s emotions, such as fear or uncertainty, are experienced, and that such power differences can intensify one’s sense of interpersonal risk (Fineman 2000).

The feelings of power imbalance and lack of psychological safety were primarily felt among non-medical staff. Nurses and receptionists were often the last to find out about clinical updates or be invited to group discussions. PO mostly tried to address this through increased frequency of communication, via email updates and WhatsApp messaging; however, this was not always successful in maintaining interprofessional relationships. Practices where leadership improved communication between disciplines saw less fracturing of relationships. Arguably, dominant hierarchical leadership styles may have been of benefit early in the pandemic, given the significant emotional and financial strains on practices where business decisions were also a priority. However, this also had repercussions, as evidenced in frustration at exclusion from decision-making felt by nursing and reception staff at one practice once the early chaos had settled. CHC staff were the only ones to comment on their hierarchical organisational structure specifically, and in contrast to many smaller practices, they viewed their hierarchy as beneficial during this time, providing guidance through concrete rules and protocols when so many routines had been disrupted.

Communication

Researchers have reported that clinician leaders perceive interpersonal skills and communication to be the most important leadership competencies (Standiford et al. 2021), and highlighted the importance of communication to manage and negotiate change, utilising team meetings and other methods (Levesque et al. 2018). Although the pandemic disrupted typical in-person communication practices, this study revealed the multiple new forms of communication that practice teams developed, and provided examples of how communication was seen as both a barrier and an invitation to a wider sense of team cohesion. Practices that involved the broader practice team in clinical meetings and WhatsApp groups, such as nurses and receptionists, felt more united. By comparison, when teams limited communication between ‘levels of hierarchy’, members felt insecure and overwhelmed, particularly in smaller practices. The constant changes to clinical recommendations from the State and Federal Governments were highlighted; at times, delays in communicating these changes added further stresses to decisions about finances, logistics and resourcing of equipment. These factors emphasise the need for more streamlined communication pathways at both practice and Government levels during crises. Potential strategies to improve communication in crises include creation of separate channels for: (1) new information/policy change; (2) informal chat to discuss individual concerns; and (3) practice-wide chat to include all GP staff.

Emergent leaders

Prior pandemics have highlighted that moments of extreme stress provide a powerful opportunity for leadership development (Standiford et al. 2021; Geerts et al. 2021). Our study provided examples of visionary leadership, primarily within the CHC, and at instances within W and CBD. The rarity of these opportunities may reflect lack of senior leadership support or simply lack of invitation to workers to take on leadership roles given the circumstances. In practices that experienced leadership change during the pandemic, emergence of leaders generally represented an inherent ‘need’ for an authoritative figure, rather than deliberate fostering of leadership development through encouraging qualities amongst members, as described by Crabtree’s attribute. The CHC was the exemplar, as it demonstrated most of the attributes of the Crabtree model, which facilitated swifter and more effective change through engaging and motivating staff who felt psychologically safe and developed a collective mind.

Despite the limitations outlined above, a strength of primary care during the pandemic was the ability to adapt quickly to the rapidly evolving situation. Nearly all practices were able to successfully mount a relatively rapid response to the pandemic. A key learning is that maintaining a practice’s ability to do so through coherent local leadership is inherent to its ability to deal with crises. Strategies for leaders need to reflect that learning is multifactorial: cognitive, interpersonal and organisational factors should be considered.

Limitations

Although data were collected from practices with a range of organisational models, these were limited to a single Australian city in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, which by international standards experienced very strict lockdowns and low rates of infection. Different leadership practices may have emerged from rural practices, those not faced by a city-wide lockdown and in practices with no association with a university Department of General Practice. Although the iterative lens adopted to view this data was thoroughly considered, we acknowledge that Crabtree et al.’s attributes were developed in studies that selected ‘high-performing’ practices, conducted during times of planned change, as opposed to the unplanned changes this analysis explored. The leadership model was not specifically addressed in initial data collection; rather, in this secondary analysis, codes were applied where best possible, which provides potential for biased selection or missed data.

Despite these limitations, our study was strengthened by its prospective framework, iterative analysis process, and use of investigators both within and outside the practice, further ensuring that results provide an unbiased representation of the experience of Victorian practice teams during the 2020 period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implications for future practice

This study examined practices against Crabtree’s conceptually based, literature-informed model of leadership for primary care practices. This framework helped to identify potential approaches that could better prepare practice teams for crises. All practices had a clear hierarchy, mostly the traditional Australian structure of private GP owners as the dominant leaders (SE1, E and CBD; Moel-Mandel and Sundararajan 2021). Addressing power imbalance is important to facilitate both optimum patient care and increased collaboration. Awareness of how hierarchal organisational structures impact team contribution, collaboration and acknowledgement of members’ roles is important for supporting team cohesion (Edwards et al. 2022). Lack of identified formal training of GP leaders in crisis management, communication and, importantly, leadership skills, highlights a pitfall in preparedness of the local system for further health crises. Training of the wider practice team, particularly in crisis management, can potentially promote interdisciplinary communication,≠ and transparency and trust between practice leaders and practice members, and help address the issues raised here on a systemic level.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of Sharron Clifford, project manager at Monash University, who helped coordinate the study, as well as Jessica Hinh, who contributed to the secondary analysis. Additionally, we acknowledge Liz Sturgiss, Simon Hattle and Timothy Staunton Smith who were all clinician investigators.

References

Balasubramanian BA, Chase SM, Nutting PA, Cohen DJ, Strickland PAO, Crosson JC, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, the ULTRA Study Team (2010) Using learning teams for reflective adaptation (ULTRA): insights from a team-based change management strategy in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 8, 425-432.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Becker MC (2004) Organizational routines: a review of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change 13(4), 643-678.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Boroujeni M, Saberian M, Li J (2021) Environmental impacts of COVID-19 on Victoria, Australia, witnessed two waves of Coronavirus. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28, 14182-14191.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braithwaite J, Tran Y, Ellis LA, Westbrook J (2021) The 40 health systems, COVID-19 (40HS, C-19) study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 33, mzaa113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Crabtree BF, Howard J, Miller WL, Cromp D, Hsu C, Coleman K, Austin B, Flinter M, Tuzzio L, Wagner EH (2020) Leading innovative practice: leadership attributes in LEAP practices. Milbank Q 98, 399-445.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Desborough J, Dykgraaf SH, Phillips C, Wright M, Maddox R, Davis S, Kidd M (2021) Lessons for the global primary care response to COVID-19: a rapid review of evidence from past epidemics. Family Practice 38, 811-825.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Donahue KE, Halladay JR, Wise A, Reiter K, Lee SY, Ward K, Mitchell M, Qaqish B (2013) Facilitators of transforming primary care: a look under the hood at practice leadership. Annals of Family Medicine 11(Suppl 1), S27-S33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Edmondson AC (2003) Speaking up in the operating room: how team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies 40, 1419-1452.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Edwards S, Gordon L, Guzman CEV, Tuepker A, Park B (2022) Perspectives of primary care leaders on the challenges and opportunities of leading through the COVID-19 pandemic. The Annals of Family Medicine 20, 2891.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Finlayson M, Sheridan N, Cumming J (2009) Nursing developments in PHC 2001-07, Health Services Research Centre, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Available at http://www.victoria.ac.nz/hsrc/reports/previous-reports_2009.aspx

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S (2013) Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13(1), 117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Geerts JM, Kinnair D, Taheri P, Abraham A, Ahn J, Atun R, Barberia L, Best NJ, Dandona R, Dhahri AA, Emilsson L, Free JR, Gardam M, Geerts WH, Ihekweazu C, Johnson S, Kooijman A, Lafontaine AT, Leshem E, Lidstone-Jones C, Loh E, Lyons O, Neel KAF, Nyasulu PS, Razum O, Sabourin H, Schleifer Taylor J, Sharifi H, Stergiopoulos V, Sutton B, Wu Z, Bilodeau M (2021) Guidance for health care leaders during the recovery stage of the COVID-19 pandemic: a consensus statement. JAMA Network Open 4, e2120295.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kippen R, O’Sullivan B, Hickson H, Leach M, Wallace G (2020) A national survey of COVID-19 challenges, responses and effects in Australian general practice. Australian Journal of General Practice 49, 745-751.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lane R, Russell G, Bardoel EA, Advocat J, Zwar N, Davies PGP, Harris MF (2017) When colocation is not enough: a case study of General Practitioner Super Clinics in Australia. Australian Journal of Primary Health 23, 107-113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Levesque JF, Harris MF, Scott C, et al. (2018) Dimensions and intensity of inter-professional teamwork in primary care: evidence from five international jurisdictions. Family Practice 35(3), 285-294.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McInnes S, Peters K, Bonney A, Halcomb E (2015) An integrative review of facilitators and barriers influencing collaboration and teamwork between general practitioners and nurses working in general practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 71, 1973-1985.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Stange KC, Jaén CR (2010) Primary care practice development: a relationship-centered approach. Annals of Family Medicine 8, S68-S79.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moel-Mandel C, Sundararajan V (2021) The impact of practice size and ownership on general practice care in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 214, 408-410.e1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Plsek PE, Wilson T (2001) Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations. BMJ 323(7315), 746-749.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rogers L, De Brún A, Birken SA, Davies C, McAuliffe E (2020) The micropolitics of implementation; a qualitative study exploring the impact of power, authority, and influence when implementing change in healthcare teams. BMC Health Services Research 20, 1059.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Russell G, Advocat J, Geneau R, Farrell B, Thille P, Ward N, Evans S (2012) Examining organizational change in primary care practices: experiences from using ethnographic methods. Family Practice 29, 455-461.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Russell G, Advocat J, Lane R, et al. (2021) How do general practices respond to a pandemic? Protocol for a prospective qualitative study of six Australian practices. BMJ Open 11(9), e046086.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Russell G, Lane R, Neil J, et al. (2023) At the edge of chaos: a prospective multiple case study in Australian general practices adapting to COVID-19. BMJ Open 13(1), e064266.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Standiford TC, Davuluri K, Trupiano N, Portney D, Gruppen L, Vinson AH (2021) Physician leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: an emphasis on the team, well-being and leadership reasoning. BMJ Leader 5(1), 20-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19, 349-357.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Verhoeven V, Tsakitzidis G, Philips H, Van Royen P (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the core functions of primary care: will the cure be worse than the disease? A qualitative interview study in Flemish GPs. BMJ Open 10, e039674.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Appendix 1.Comparative and cross case analysis

| Attributes | CHC | SE1 | E | CBD | SE2 | W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivating others to engage in change | Collective sense of transformational leadership, supported by the governing body of the centre, and quick-thinking nurses to implement a COVID-19 committee early on. ‘We’ve been able to adapt fairly quickly because we’ve been supported’. | Initial hesitancy by the practice owners to acknowledge the severity of the situation and initiate change… ‘in the early days it was horrible’, ‘no one was united – everyone had their own opinion’. This resulted in practice GPs uniting to motivate the needed change. Following this, the practice meetings ‘got better and better’, with the emergence of further leaders | Unilateral decisions made by the practice principals limited the contributions from practice team members early on. While GP input seems ‘appreciated’, all decisions were made by owners. Despite some feelings of increased ‘collaboration’, it was still evident that there was a leader whom had to be followed | Practice owner was seen as the main driver of change, with collaborative decisions being made early on; ‘Most staff have been on board as they were able to have a say and air their views’ | Distant and delayed communication from the governing body resulting in the practice feeling unsupported early on. Appointment of a GP clinical lead introduced opportunity for regular meetings with PM and lead nurse, resulting in greater practice unity | Leadership roles transferred quickly from board members onto individual team leads to keep the practices ‘head above water’. Change in leadership, more agility and less structured approval processes facilitated greater workplace flow and COVID-19 screening processes | |

| Power hierarchy and psychological safety * Collapsed attribute | Established hierarchy viewed positively within the practice, given practice context and large governing body who can make decisions and rules quickly. No strong feelings of isolation/power abuse amongst staff | Certain cohorts within the practice team felt the impact of organisation hierarchy greater than others. Initially, reception and PNs felt ‘on the outer’ – not part of conversations or decision making, however reception note that in later stages of the pandemic, more frequent invitation to join meetings, improved feelings of inclusion, dismissed feelings of historical hierarchical boundaries | Strong early leadership by one practice owner caused unrest amongst some staff and limited interdisciplinary teamwork amongst remaining practice members. Nurses had particular concerns | Stepping up of practice owner, who is also a GP, to practice manager, seen positively by GPs, but placed nurse GP relationships under strain | Positive interdisciplinary relationships were generally maintained throughout the pandemic, bar a pre-existing conflict that was seen too during this time. The local leadership group played a large role in upholding this security | Existing interdisciplinary tensions that were present pre-COVID-19 remained present, and expected to post-COVID-19. No new concerns or experiences of power imbalance or lack of psychological safety | |

| Enhancing communication and information sharing | Inclusion in group chats and weekly clinical meetings across all disciplines. Weekly CEO updates and email newsletters throughout the pandemic | Contractor GPs taking it upon themselves to starts a GP WhatsApp group was the foundation to necessary whole-of-practice change. PM, nurses and receptionist not included in clinical meetings | Clinical meetings mostly invited GPs only. Nurses and receptionists received multiple daily email communications. No utilisation of other channels; WhatsApp etc. | Weekly Zoom meetings open to all staff; however, was primarily GPs attending. Doctor-only WhatsApp group with informal daily catchups between practice owner and GPs | Separate, discipline-specific group chats with PM being common member across all, relaying updates from clinical meetings attended by PM, MD, lead GP [clinical director] and lead nurses. Reception note that more formal discipline-specific meetings would have been of benefit | Two WhatsApp groups; one for all staff and one for the Directors, for daily updates. PM would touch base with receptionist often to confirm updates; however, nurses felt ‘out of the loop’ and that messages were somewhat ‘filtered down’. Continuous ‘internal mail’ | |

| Encouraging boundary spanning | Horizontal spanning: Reception convincing clients to use telehealth, reorganising telehealth – all new tasks because of COVID-19. Additional need for receptionist to upskill in triaging patients. Nurses scope of practice had not really changed, but increased workload was observed, especially with GPs off-site | Minimal vertical, horizontal or stakeholder boundary spanning present. Increased work demands observed within each respective discipline, but no crossing of expertise; e.g. as reception aren’t medically trained and such weren’t required to triage patients at booking, this was left for the GPs. | Horizontal boundary spanning occurred. Reception staff were trained to triage patients. Workload also increased in each respective discipline | As per other practices, increased workload within each discipline. Horizontal spanning demonstrated by receptionists; needing to send out scripts, triage patients over the phone and mediate anxious patients | Horizontal spanning; greater need for reception to screen and triage patients over the phone for in-person consultations. ‘Less patients coming in, but more work’. | Stakeholder spanning; liaison with Federal Government for respiratory clinic establishment and formal government training in COVID-19 infection control and risk screening. Horizontal spanning; recruitment of health assistants – nursing and paramedic students, retail, hospitality or ex-pilots who had lost their job due to COVID-19. | |

| Team with a collective mind * Collapsed attribute | GPs reflect that pandemic bought WFH GPs and on-site staff closer (e.g. nurses), however, was already a very close practice – ‘the practice on the whole has responded quite well’. Established ‘teamwork’ routines in place due to levels of hierarchy within the practice | Lack of perceived ‘seriousness’ of the pandemic early on limited the uniting of a ‘collective mind’. Established ‘teamwork’ [routines and compliance] of an established smaller practice were solid, despite some early miscommunication between GPs and receptionists | Many staff remained working on site. GPs, mainly contractors, generally all abided by policies and procedures despite the practice being just ‘a place of work’ – ‘good relationships were maintained during the pandemic but they were not brought closer together because of it.’ | Most relationships within the practice were maintained. Nurses and receptionists got closer, similarly the GP group were also bought closer. Some interdisciplinary issues between part time GPs and nurses regarding adhering to policy, not contributing to ‘collective practice’, but this is now ‘on the mend’ | Larger practice with numerous GPs within a corporate model resulted in challenges to cultivate teamwork and instil a collective mind. Early difficulties with profit driven vs best clinical practice decisions saw initial poor team cohesion. Ultimately, CII states ‘practice closer together than before pandemic’ | Early change in leadership meant changes to communication styles, seen favourably in the sense of greater feelings of ‘teamwork’ and interpersonal relationships. Some issues with ‘collective mind’, a reflection of being a larger practice with 8 GP part owners | |

| Fostering emergent leaders | Change of leadership just prior to the pandemic – GM stepped in as PM followed by formal appointment of a PM from within the organisation. Positive accounts all-around. nurses stepped up and initiated a COVID-response committee very early on in the pandemic, of her own accord | Contractor GPs collaborated to construct a formal email highlighting the need for change within the practice. Practice leadership, primarily practice owner, took this feedback and ran with it – resulting in improved and more organised communication channels | Minimal change or emerging of leaders seen within E. Potential barriers to fostering leaders seen in existing established practice leadership and lack of opportunity to collaborate as wider practice team | CBDs vacant PM position was readily filled by the enthusiastic and experienced practice owner, who saw the pandemic as a chance to ‘give back’ after her many years of training | Lack of local clinical leadership [lead GP] position early initially saw SE2 struggling to foster ‘team’ environments. The appointment of GP clinical lead saw improved cohesion amongst the leadership team and wider practice. PM and lead nurses initially had lots to manage | Transition from board members to local team leads was ultimately the best thing to happen for the practice. Increased individual responsibility and a strengthening of the practice team allowed for the successful implementation of the respiratory clinic, and changes to decision-making processes that were for the better | |

| Generating a learning organisation | New management/leadership at start of pandemic instilled confidence within the longer-term staff, creating an environment that supports change | Thoughts that practice owner who stepped into leadership position had been ‘low grade frustrated’ prior to COVID-19 [regarding decision-making etc.], but the pandemic in a sense gave him opportunity to flourish; new energy | Organisational learning was able to be fostered through a combination of strong leadership, minimal resistance to change and openness to adapt. Success of practice change also thought to be complemented by location of practice; high SES status with well-educated patient base | Creativity, shown through the practices adaptive reserve, in addition to leadership with a clinical background created an environment that was able to generate change. Benefit of having medical leaders within a medical practice is the driver of change is clinical in nature, in addition to financial | Feelings that corporate model of practice limited ability to build ‘team ethos’, especially amongst GPs. This, in turn, established some barriers to implementing successful change. Despite this, reflections that COVID-19 overall had a ‘unifying affect’ that will remain | New leadership structure supported changes to decision making processes, allowing a quicker approval process and greater contribution from the wider practice |