Best-practice recommendations to inform general practice nurses in the provision of dementia care: a Delphi study

Caroline Gibson A B * , Dianne Goeman A C , Mark Yates B D and Dimity Pond A

A

A Faculty of Health and Medicine, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia.

B Grampians Health, Ballarat, Vic. 3350, Australia.

C Central Clinical School, Monash University, The Alfred Centre, Melbourne, Vic. 3004, Australia.

D Deakin University School of Medicine, Ballarat Clinical School, Ballarat, Vic. 3350, Australia.

Australian Journal of Primary Health - https://doi.org/10.1071/PY22276

Submitted: 26 July 2022 Accepted: 27 May 2023 Published online: 22 June 2023

© 2023 The Author(s) (or their employer(s)). Published by CSIRO Publishing on behalf of La Trobe University. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND)

Abstract

Background: Worldwide, responsibility for dementia diagnosis and management is shifting to primary care, in particular to the general practitioner (GP). It has been acknowledged that primary care nurses, working collaboratively with GPs, have a role in dementia care by utilising their unique knowledge and skills. However, there are no best-practice guidelines or care pathways to inform nurses in general practice on what best-practice dementia care comprises and how to implement this into their practice. This study identified the recommendations in the Australian guidelines for dementia management most relevant to the role of the nurse working in general practice.

Methods: Seventeen experts active in clinical practice and/or research in primary care nursing in general practice participated in an online three-round Delphi study.

Results: All 17 participants were female with a nursing qualification and experienced in general practice clinical nursing and/or general practice nursing research. Five recommendations were identified as the most relevant to the role of the nurse in general practice. These recommendations all contained elements of person-centred care: the delivery of individualised information, ongoing support, including the carer in decision-making, and they also align with the areas where GPs want support in dementia care provision.

Conclusion: This novel study identified best-practice dementia care recommendations specific to nurses in general practice. These recommendations will inform a model of care for nurses in the provision of dementia care that supports GPs and better meets the needs of people living with dementia and their carer(s).

Keywords: health services: aged, nursing: assessment, nursing: process, patient care: management, patient-centred care, primary health care.

Introduction

Dementia prevalence is increasing with global population growth and aging, placing significant pressures on already strained healthcare systems. World-wide public health policy is shifting the responsibility for dementia diagnosis and management away from secondary health care to primary care settings, in particular general practice. Supporting a primary care led approach to dementia is a more efficient use of healthcare resources (Frost et al. 2020). Additionally, it’s holistic approach to care can lead to a higher quality of life and improvement in the health and wellbeing of people living with dementia (Spenceley et al. 2015), potentially extending time living in the place of their choice. However, with its complex physical, behavioural and psychosocial needs, dementia is poorly recognised, diagnosed and managed within general practice (Beck et al. 2021). GP barriers to optimal dementia care include lack of knowledge and skills in the management of this disease and insufficient time to provide support to the person living with dementia and their carer (Heintz et al. 2020). Additionally, global GP shortages may also impact on the provision of optimal dementia care in the general practice setting due to the resulting structural barriers such as reduced access to a GP and time-limited consultations.

Nurses working in general practice, henceforth referred to as general practice nurses (GPNs), are qualified nurses with varying scopes of practice depending on their level of education and professional registration. GPNs have a diversity of roles including clinical care, chronic disease management, health promotion and administration. They are key to complementing the role of the GP (McInnes et al. 2015) and the co-ordination of patient care before, during, and after the GP consult (Swanson et al. 2020). Given their breadth of practice, the majority of GPNs will encounter people living with dementia and their carer(s). It has been acknowledged that GPNs have a role in supporting the GP in better meeting the diverse and complex needs of people living with dementia and their carers, potentially through the provision of person-centred dementia care and less restricted time limits (Islam et al. 2020).

A review of recent literature shows that GPNs have limited knowledge in relation to the recognition of cognitive impairment and person-centred care for people living with dementia (Evripidou et al. 2019). This suggests that they will need support to provide optimal care to people living with dementia. Dementia care guidelines and pathways for dementia care delivered by GPs exist (Ngo and Holroyd-Leduc 2015); however, there is little evidence on models of care or clinical practice guidelines directed to GPNs in their delivery of dementia care (Gibson et al. 2020). The current Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia (Guidelines Adaptation Committee 2016) (henceforth referred to as The Guidelines) are written for health practitioners in general, and not for any specific end-user. The Guidelines contain 109 recommendations for the optimal diagnosis and management of dementia divided into 21 components of care. The most effective models of care are informed by evidence-based clinical practice guidelines customised for the intended end-user (Graham et al. 2006). A recent Delphi study (Mazza et al. 2021) identified priority recommendations in Guidelines (Guidelines Adaptation Committee 2016) relevant to GP provision of dementia care, including which of these recommendations GPs required support to implement.

Our study identified which of the 109 recommendations in The Guidelines were most relevant to the role of the GPN in the provision of dementia care. To our knowledge, our study is the first to identify best practice dementia care guideline recommendations specific to GPN practice.

Methods

Aim

To identify the recommendations included in the Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia (Guidelines Adaptation Committee 2016) that are most relevant to the role of the GPN in the provision of best-practice dementia care.

Design

A Delphi consensus method (Keeney et al. 2011) was used to address our research aim. The purpose of this method is to achieve consensus among a group of experts on a certain issue where no agreement previously existed. Three rounds of an online survey containing the recommendations as written in The Guidelines were administered to panel members. A protocol (Gibson et al. 2021a) has been published for this study.

Participants and recruitment

Purposeful identification and recruitment of an expert panel of general practice nursing key stakeholders was undertaken. In this study, an expert was defined as a person who is knowledgeable about the subject being investigated (Keeney et al. 2011). Purposive sampling ensured that the panel members were nurses experienced in clinical practice and/or research, in general practice nursing.

In qualitative Delphi studies that do not involve hypothesis testing, a panel size of 6–50 members are recommended (Birko et al. 2015). In this study, a purposive sample of 28 experts were identified through the study teams’ professional networks and invited to participate via email. The invitation included a personalised letter with participant information and a consent form. Seventeen experts agreed to participate with the return of written consent to the researcher via email.

Procedure

The survey was administered using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform (Harris et al. 2009). Data collection took place between September and November 2021 inclusive. This study was reported using the Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) (Junger et al. 2017).

Three Delphi survey rounds were employed. The link to the first-round survey was sent to all 17 panel members on the same date via email. Two weeks were provided to complete each survey round, with up to three email reminders sent 7, 10 and 13 days after the initial invitation. Included in each of survey rounds two and three, panel members received a summary of their own responses and the group responses to the recommendations included in the previous round. In each of survey round two and three, panel members were asked to reconsider the recommendations for which consensus has not been reached. The panel members were anonymous to each other.

All 17 expert panel members were invited to participate in every round independent of response to the previous round. This approach was taken as it potentially results in a better representation of opinions of the originally invited panel and reduces the chance of false consensus (Boel et al. 2021).

Survey instrument

The RedCap platform (Harris et al. 2009) was used to develop and distribute the survey. The functionality of the online survey instrument was pre-tested with four GPNs with no changes required. An option was provided to grade each recommendation using a four-point Likert scale in response to the question ‘Please indicate how relevant each recommendation is to the role of the GPN?’ The four possible responses were ‘extremely relevant’, ‘moderately relevant’, ‘not directly relevant’ or ‘not at all relevant’. Qualification of responses or suggestions for additional recommendations were not sought as this study was limited to identifying those recommendations contained in the most recent Australian best-practice guidelines for dementia care that were rated as relevant to the GPN. The first survey round included questions on demographic characteristics to provide a description of the characteristics of the expert panel.

Prior to data collection, the cut-off for consensus was defined as 75% (Keeney et al. 2011). Survey rounds two and three were comprised of recommendations from the previous round, which did not meet consensus for any of the response options and required re-rating by panel members.

Data analysis

For each survey round, data were exported from the REDCap survey (Harris et al. 2009) and aggregated in tabular form for visualisation and manual analysis. Reports on individual and group responses generated using the RedCap platform (Harris et al. 2009) were returned to participants to provide feedback and to generate the next round. The recommendations that were endorsed as constituting best practice dementia care by GPNs were those recommendations identified as ‘extremely relevant’ to the role of the GPN. Descriptive statistics were used to report the demographic characteristics of the panel members.

Patient and public involvement

Consumers of dementia care were involved in the development of the Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia (Guidelines Adaptation Committee 2016), which is central to this study.

Results

Panel demographics

Seventeen experts participated in this study. All 17 were female with 16 (94%) holding a registered nurse qualification and one nurse (6%) was an enrolled nurse. Eleven (65%) of the 17 experts were experienced in general practice clinical nursing only and three (18%) experts had general practice research experience, but no clinical experience. Three (18%) nurses had both general practice research and clinical experience. Demographics of the 17 members of the expert panel are shown in Table 1.

| Participants ( = 17) | ||

|---|---|---|

| % | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 17 | 100 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 1 | 5.9 |

| 30–39 | 1 | 5.9 |

| 40–49 | 3 | 17.6 |

| 50–59 | 8 | 47.1 |

| 60+ | 4 | 23.5 |

| State of residence | ||

| New South Wales | 4 | 23.5 |

| South Australia | 1 | 5.9 |

| Victoria | 12 | 70.6 |

| Type of nursing qualification | ||

| Registered Nurse | 16 | 94.1 |

| Enrolled Nurse | 1 | 5.9 |

| Clinical experience as a general practice nurse only | 11 | 65 |

| General practice nursing research expertise only | 2 | 12 |

| Both clinical experience as a general practice nurse and general practice nursing research expertise | 4 | 24 |

Panel response rates

There was a 100% (n = 17) response rate for survey round one, a 94% (n = 16) response rate for survey round two and an 88% (n = 15) response rate for survey round three.

Technical issues mean that six of the 109 (n = 6, 6%) questions to rate recommendations were missed by one participant in round one. A review of round one revealed that these six recommendations would not have reached consensus for inclusion or exclusion regardless of the option chosen by this panel member. The technical issue was corrected, and all six questions were included in survey round two.

Recommendations reaching consensus as relevant to the GPN role

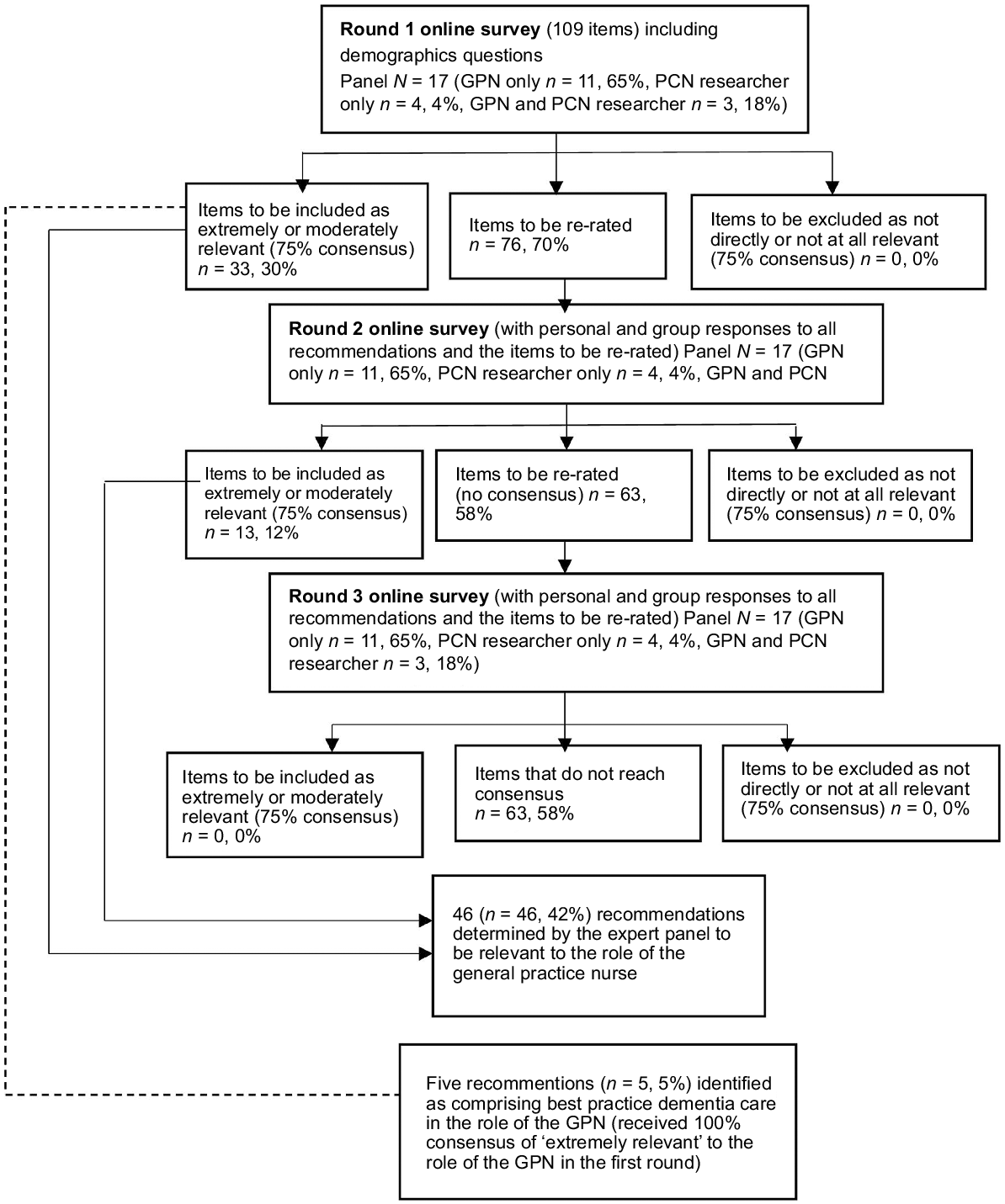

At the conclusion of the three survey rounds, 46 (42%) recommendations contained in The Guidelines reached consensus level (75%) as ‘extremely relevant’ to the role of the GPN (Supplementary File S1). Fig. 1 describes the consensus outcomes through the three survey rounds.

Five recommendations (22%) received 100% consensus of ‘extremely relevant’ to the role of the GPN in the first round (Table 2). As a result of this strength of consensus, these five recommendations have been acknowledged as the components of dementia care most relevant to the role of the GPN.

| Health and aged care professionals should use language that is consistent with the Dementia Language Guidelines and the ‘Talk to me’ good communication guide for talking to people with dementia (Principles of care, Recommendation 3) |

| If language or culture is a barrier to accessing or understanding services, treatment and care, health and aged care professionals should provide the person with dementia and/or their carer(s) and family with information in the preferred language and in an accessible format, professional interpreters, and interventions in the preferred language (Barriers to access and care, Recommendation 9) |

| Health professionals should consider the needs of the individual and provide information in a format that is accessible for people with all levels of health literacy and considering the specific needs of people with dysphasia or an intellectual disability (Barriers to access and care, Recommendation 10) |

| Health and aged care professionals should be aware that people with dementia, their carer(s) and family members may need ongoing support to cope with the difficulties presented by the diagnosis (Information and support for the person with dementia, Recommendation 50) |

| Carers and families should be respected, listened to, and included in the planning, decision-making and care and management of people with dementia (Support for carers, Recommendation 99) |

The five (22%) recommendations that reached 100% consensus and therefore identified as most relevant to the role of the GPN were contained within five components of care. These five components of care were: Principles of care; Ethical and legal issues; Barriers to access and care; Information and support for the person with dementia; and Support for carers.

Recommendations not reaching consensus as relevant to the GPN role

Sixty-three of the recommendations (58%) contained in The Guidelines did not reach consensus for any category.

No recommendations were relevant to the GPN role within the following components of care: Specialist assessment services; Neuroimaging; Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine; Nutritional supplement; and Palliative approach.

Discussion

This Delphi study identified five recommendations, from a total of 109 contained in the Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia (Guidelines Adaptation Committee 2016), as the most relevant to the role the GPN. These five recommendations received 100% consensus in the first round of the Delphi study. Each of these five recommendations contain elements of person-centred care. This is consistent with best practice dementia care being person-centred (Fazio et al. 2018). Four of these recommendations describe the use of appropriate language and individualised information, which is inherent in supporting a person living with dementia to be an active participant in their care, an essential component of person-centred care. The other selected recommendation states including family carers, if available, in decision-making. It is not surprising that the expert panel selected these five recommendations as the most relevant as they align with the role of the GPN, which has been described by Phillips et al. (2011) as patient carer, organiser, quality controller, problem-solver, educator and agent of connectivity (Phillips et al. 2011).

A review of recent literature shows that GPNs have limited knowledge in relation to the recognition of cognitive impairment and person-centred care for people living with dementia (Evripidou et al. 2019). Significantly, there is a misalignment between nurses’ belief that their practice is person-centred and their actual practice (Byrne et al. 2020) resulting in poor operationalisation of person-centred care. This is a concern given best practice dementia care is person-centred (Fazio et al. 2018). It is acknowledged that provision of care for people living with dementia and/or support person(s) can be challenging due to complex psycho-social-medical needs; however, regardless of their role and expertise, GPNs need to possess the knowledge and skills to provide high-quality care to all patients they encounter in general practice (Halcomb et al. 2019), including those impacted by dementia.

Team-based care and the effectiveness and sustainability of GP and GPN collaborative and complementary models of care are well established in chronic disease management (Halcomb et al. 2008). However, both GPs and GPNs have indicated they require practical guidance and shared models of care to better meet the diverse and complex needs of people living with dementia and their support person(s) (Gibson et al. 2021b; Mazza et al. 2021).

Mazza et al. (2021) conducted a Delphi study, using the same guidelines, to identify priority recommendations for GP practice and areas where the GP required support in implementation. The areas in which GPs required support included addressing information and support needs of people living with dementia and/or support person(s) with different levels of health literacy, cultural and language preferences and access to services (Mazza et al. 2021). In addition to integrating dementia care into their own practice, the GPN can provide further value in provision of dementia care as the recommendations most relevant to their role align with the areas where GPs want support.

Study strengths and limitations

A Delphi process is useful in achieving consensus among a group of experts on a certain issue where no agreement previously existed (Keeney et al. 2011). The Delphi process enables group input on an issue that may not otherwise be possible due to geography, time and currently, a pandemic. It also enables anonymous input unaffected by power relationships between the respondents. The credibility of this Delphi study and the validity and reliability of the findings was optimised by following a pre-determined methodology (Gibson et al. 2021a) and reported using the CREDES guidelines (Junger et al. 2017). A strength of the study was that all expert panel members held a nursing qualification and experience in clinical general practice nursing and/or extensive research in the field of general practice nursing.

There are limitations in using a qualitative Delphi methodology as the expert panel may not be representative of all general practice nursing contexts, this limiting generalisations (Keeney et al. 2011). An additional limitation may be the lack of geographic spread with only three of the six states and territories of Australia represented on the expert panel. This study used a small sample; however, it has been argued that a small sample size is valid in Delphi methodology when not testing a hypothesis (Birko et al. 2015). In addition, expertise in the topic under investigation is more valuable to validity than sample size (Keeney et al. 2011). There may be a respondent bias as one panel member skipped six questions in survey round one as the survey instrument did not require a response to all questions. However, this was corrected after the first round and there was a stability of responses through the three rounds, which is a more reliable indicator of internal validity (Keeney et al. 2011).

Future research

The findings of this Delphi study identify priority recommendations to include in a model of care for the provision of dementia care in general practice by the GPN. It is acknowledged that there will be other components to a model of care beyond these recommendations, including collaboration with the GP. A future study will aim to identify barriers and enablers to, and strategies to support, the implementation of the recommendations most relevant to the GPN role, which included person-centred care for patients impacted by dementia. The future study will also build on the findings in this Delphi study by identifying any additional recommendations that GPNs perceive as important in their provision of care to patients impacted by dementia.

Conclusion

There is currently no model of care to support the GPN in the provision of dementia care in general practice. This Delphi study identified five recommendations, included in the Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines and Principles of Care for People with Dementia, as the most relevant to the role of the GPN. These five recommendations should be prioritised in the development of a model of care tailored to the role of the GPN in providing care for people living with dementia and their support person(s), and supporting the GP in the identification and ongoing management of dementia in general practice.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available in the article and accompanying online supplementary material.

Conflicts of interest

DP and MY were members of the original Australian Clinical Practice Guideline and Principles of Care for People with Dementia development consensus group; however, as they have had no direct role in the identification of the guidelines that are relevant to general practice nurses in this Delphi process, they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

This research contributes to a larger program of work being conducted by the Australian Community of Practice in Research in Dementia (ACcORD), which is funded by a Dementia Research Team Grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council. CG is supported by a University of Newcastle Postgraduate Research Scholarship from the Faculty of Health and Medicine.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Delphi Expert Panel for their time and invaluable input in relation to the topic investigated.

References

Beck AP, Jacobsohn GC, Hollander M, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Werner N, Shah MN (2021) Features of primary care practice influence emergency care-seeking behaviors by caregivers of persons with dementia: a multiple-perspective qualitative study. Dementia 20, 613-632.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Birko S, Dove ES, Özdemir V (2015) Evaluation of nine consensus indices in Delphi foresight research and their dependency on Delphi survey characteristics: a simulation study and debate on Delphi design and interpretation. PLoS ONE 10, e0135162.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Boel A, Navarro-Compán V, Landewé R, van der Heijde D (2021) Two different invitation approaches for consecutive rounds of a Delphi survey led to comparable final outcome. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 129, 31-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Byrne A-L, Baldwin A, Harvey C (2020) Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: an integrative review. PLoS ONE 15, e0229923.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Evripidou M, Charalambous A, Middleton N, Papastavrou E (2019) Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes about dementia care: systematic literature review. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 55, 48-60.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fazio S, Pace D, Flinner J, Kallmyer B (2018) The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist 58, S10-S19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Frost R, Rait G, Aw S, Brunskill G, Wilcock J, Robinson L, Knapp M, Hogan N, Harrison Dening K, Allan L, Manthorpe J, Walters K, on behalf of the PriDem team (2020) Implementing post diagnostic dementia care in primary care: a mixed-methods systematic review. Aging & Mental Health 25, 1381-1394.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson C, Goeman D, Pond D (2020) What is the role of the practice nurse in the care of people living with dementia, or cognitive impairment, and their support person(s)?: a systematic review. BMC Family Practice 21, 141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson C, Goeman D, Yates M, Pond D (2021a) Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia: a protocol for undertaking a Delphi technique to identify the recommendations relevant to primary care nurses in the delivery of person-centred dementia care. BMJ Open 11(5), e044843.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gibson C, Goeman D, Hutchinson A, Yates M, Pond D (2021b) The provision of dementia care in general practice: practice nurse perceptions of their role. BMC Family Practice 22, 110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N (2006) Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26, 13-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Guidelines Adaptation Committee (2016) Clinical practice guidelines and principles of care for people with dementia. (NHMRC Partnership Centre for Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People: Sydney, Australia) Available at https://cdpc.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CDPC-Dementia-Guidelines_WEB.pdf

Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM, Salamonson Y, Ollerton R, Griffiths R (2008) Nurses in Australian general practice: implications for chronic disease management. Journal of Clinical Nursing 17, 6-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Halcomb EJ, McInnes S, Patterson C, Moxham L (2019) Nurse-delivered interventions for mental health in primary care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Family Practice 36, 64-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42, 377-381.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Heintz H, Monette P, Epstein-Lubow G, Smith L, Rowlett S, Forester BP (2020) Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: a narrative review. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 28, 320-330.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Islam MM, Parkinson A, Burns K, Woods M, Yen L (2020) A training program for primary health care nurses on timely diagnosis and management of dementia in general practice: an evaluation study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 105, 103550.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Junger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG (2017) Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliative Medicine 31, 684-706.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mazza D, McCarthy E, Camões-Costa V, Mansfield E, Bryant J, Waller A, Lin X, Piterman L (2021) Prioritising national dementia guidelines for general practice: a Delphi approach. Australasian Journal on Ageing 41, 247-257.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McInnes S, Peters K, Bonney A, Halcomb E (2015) An integrative review of facilitators and barriers influencing collaboration and teamwork between general practitioners and nurses working in general practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 71, 1973-1985.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ngo J, Holroyd-Leduc JM (2015) Systematic review of recent dementia practice guidelines. Age and Ageing 44, 25-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Phillips J, Pond D, Goode SM (2011) Timely Diagnosis of Dementia: can we do better? A report for Alzheimer’s Australia. Paper 24. (Alzheimer’s Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia) Available at https://www.dementia.org.au/sites/default/files/Timely_Diagnosis_Can_we_do_better.pdf

Spenceley SM, Sedgwick N, Keenan J (2015) Dementia care in the context of primary care reform: an integrative review. Aging & Mental Health 19, 107-120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Swanson M, Wong ST, Martin-Misener R, Browne AJ (2020) The role of registered nurses in primary care and public health collaboration: a scoping review. Nursing Open 7, 1197-1207.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |