One Health in NSW: coordination of human and animal health sector management of zoonoses of public health significance

Sheena Adamson A C , Andrew Marich A and Ian Roth BA Centre for Health Protection, NSW Department of Health

B Department of Primary Industries

C Corresponding author. Email: sheena.adamson@doh.health.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 22(6) 105-112 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB11003

Published: 25 July 2011

Abstract

Zoonoses of public health significance may occur in wildlife, livestock or companion animals, and may be detected by the human or animal health sectors. Of particular public health interest are foodborne, arboviral and emerging zoonoses (known/unknown, endemic/exotic). A coordinated One Health approach to the management of zoonoses in NSW uses measures including: mutually agreed intersectoral procedures for detection and response; surveillance and notification systems for defined endemic and exotic diseases; joint meetings and exercises to ensure currency of response plans; and intersectoral communication during a response. This One Health approach is effective and ensures the interests of both the human health and animal health sectors are addressed.

Zoonoses are infectious diseases that are transmissible between vertebrate animals and humans under natural conditions.1 Zoonoses are caused by a wide variety of microorganisms and a subset of zoonotic infections may have significant public health implications that require a coordinated approach across human health and animal health sectors.

People who are exposed to animals at home, at work or elsewhere tend to be at greatest risk of zoonotic diseases. Examples of people who are especially at risk of exposure to zoonotic diseases include veterinarians and veterinary staff, wildlife officers, zoo keepers, farmers, shooters, abattoir workers, animal carers and pet owners. Because pathogens tend to have specific host species, certain infections tend to be associated with certain animal species.

This paper provides an overview of how the human and animal health sectors work collaboratively in New South Wales (NSW) to manage zoonoses. Planning for and responding to zoonotic public health threats and incidents requires an integrated, intersectoral approach that recognises the interrelationships between humans, animals and the environment, and the different interests of the sectors. This is sometimes described as the One Health approach.

Methods

Zoonotic diseases of public health significance in NSW were identified (Table 1). The arrangements for preparedness, detection, analysis and response activities across both the human and animal health sectors were compared, with particular focus on the comparative roles of NSW Health and the NSW Department of Primary Industries. Local and statewide strategies for prevention and preparedness, detection of individual clinical cases and surveillance, analysis of data, response and control were included.

|

Results

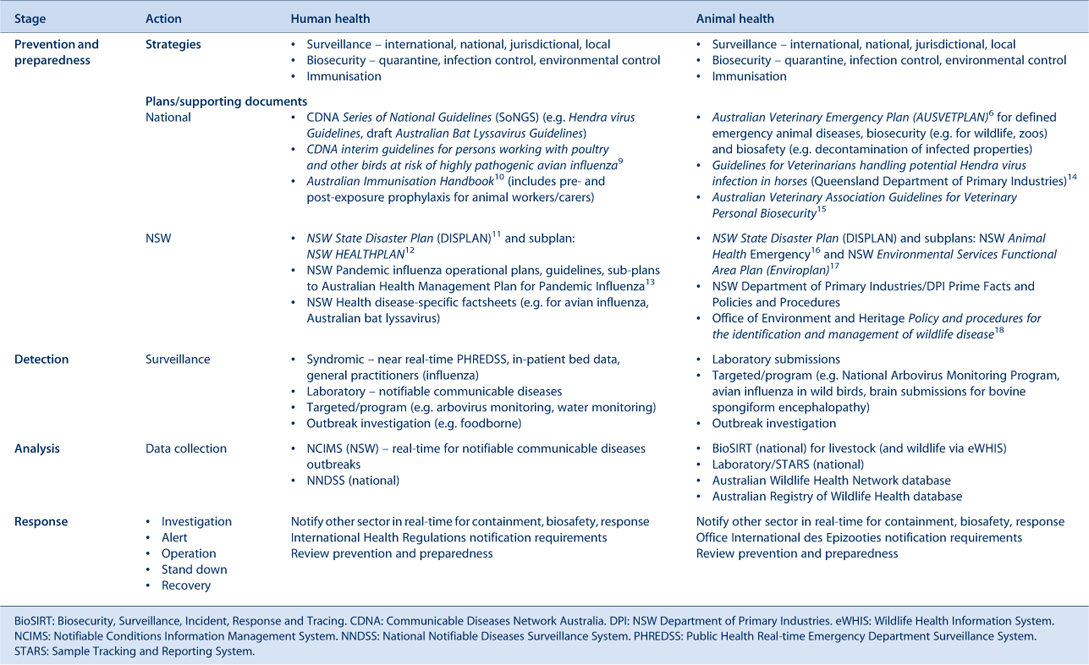

Management of zoonoses in NSW occurs in both the human and animal health sectors at the local and state level using the following strategies (Table 2).

|

General arrangements

Human health sector

NSW Health, including local health districts, has the main responsibility for human health issues in NSW, including zoonotic diseases. The Centre for Health Protection within the Population Health Division oversees both communicable diseases and environmental health issues. The Communicable Diseases Branch coordinates surveillance and response activities for statewide infectious disease issues, including zoonotic diseases, and coordinates policy development.

Operationally, NSW public health units linked with local health districts detect and respond to local infectious disease issues of public health significance and forge relationships with local stakeholders; for zoonoses, this includes those in the animal health sector.

Animal health sector

The animal health sector includes wildlife, livestock and companion animals. Overseeing the health of livestock and companion animals falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Primary Industries (DPI). Although primarily concerned with minimising any adverse impact of disease on productivity and trade, the DPI is also interested in ensuring that human health is not compromised by zoonotic diseases. The DPI works closely with Livestock Health and Pest Authorities who employ veterinarians to undertake disease control work predominately with livestock.

District Veterinarians with Livestock Health and Pest Authorities and Veterinary Officers within the DPI detect and respond to local incidents of infectious disease, including zoonotic diseases of public health significance. Regional Veterinary Officers within the DPI forge relationships and undertake most of the contact with local stakeholders, such as the local public health unit.

The health of wildlife and zoo animals falls under the jurisdiction of the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage. However, most wildlife diseases are reported through the Australian Wildlife Health Network which maintains a register of wildlife diseases and provides coordination and guidance on these diseases. The Australian Registry of Wildlife Health laboratory services include investigation of zoonoses in wildlife. The DPI coordinates significant diseases in wildlife and assists with diagnostic and field investigations.

Other sectors

Human health and safety in the workplace is the primary concern of the WorkCover Authority of NSW. WorkCover NSW is part of the Compensation Authorities Staff Division and sits within the Treasury portfolio.

The NSW Food Authority provides the regulatory framework for industry to produce safe foods and reports to the NSW Minister for Primary Industries.

Prevention and preparedness

Mutually agreed policies and procedures for managing zoonoses of public health significance are in place in both the national and jurisdictional human and animal health sectors. These are developed and maintained for currency through intersectoral agency links with contributions from other professional organisations, research facilities and universities, such as those involved with human and animal health, microbiology, epidemiology, infection control, agriculture, environment and food manufacture.

Plans for managing human and animal health emergencies, including zoonoses, are supplemented by disease-specific plans, policies, guidelines and factsheets (Table 2) which are targeted to appropriate audiences (e.g. general public, human/animal health professionals, other animal workers and carers). An important part of the management of zoonoses is the prevention of transmission, and these plans and advice sheets include recommendations for measures such as infection control and biosecurity, as well as prophylaxis through immunisation.

The national and NSW plans are tested in periodic intersectoral exercises, which in recent years have examined the response to avian influenza (Exercise Eleusis and Exercise Hippolytus) and pandemic influenza (Exercise Cumpston).2–4 They have also been tested in NSW in recent emergencies including equine influenza, pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in humans and swine, and a suspected equine Hendra virus infection investigation.

Detection

Human health sector

Zoonotic diseases in humans are diagnosed by clinicians, and selected zoonotic diseases are notifiable by clinicians and laboratories under the NSW Public Health Act 1991. Public health units enter data into a statewide database, the Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS) and these data are analysed for the local area, the state and nationally. Data are reported daily to the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. In addition, the Public Health Real-time Emergency Department Syndromic Surveillance system is occasionally used to provide complementary surveillance data arising from attendances at selected emergency departments across NSW.

Public health units also report any significant zoonotic event to the Communicable Diseases Branch when it may be of statewide significance or if the incident may have ramifications for other sectors. The Communicable Diseases Branch maintains open communication lines with counterparts in the DPI, and nationally.

In addition, public health units maintain good working relationships with DPI Regional Veterinary Officers; these officers are often the source of information about local zoonotic incidents that may have health consequences for humans.

Animal health sector

Zoonotic diseases in animals may be detected by agricultural or other animal workers, and diagnosed by Livestock Health and Pest Authorities’ District Veterinarians, DPI Veterinary Officers, veterinarians in private practice, industry or education, or through government, private and industry-specific laboratories.

National and jurisdictional surveillance and notification systems are used by the DPI to monitor the occurrence of defined endemic and exotic infectious diseases, including zoonoses, and to comply with international reporting requirements.5 Surveillance in the animal health sector is also used widely to demonstrate freedom from defined diseases for export and interstate trade purposes.

Nationally, notifiable diseases are reported quarterly by the DPI to the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry through the National Animal Health Information System administered by Animal Health Australia. Some additional diseases are only reported within NSW to the DPI. Some notifiable diseases are also defined as emergency animal diseases with a specific response prescribed in AUSVETPLAN.6,7 Syndromic surveillance is not currently available in the animal health sector, although a national pilot is in progress.

Targeted surveillance programs

Targeted surveillance is also used in both sectors in NSW (e.g. by human health for arboviruses and waterborne diseases, and by animal health for arboviruses through the National Arbovirus Monitoring Program, and for avian influenza in wild birds).

Analysis

Human health sector

Analysis of routinely collected data on human zoonotic notifications occurs regularly at local, statewide and national levels. Single case reports of selected notifiable zoonoses prompt individual risk assessment which may involve public health unit staff interviewing the case or contacts to ascertain possible exposures, site visits, workplace assessment, enhanced surveillance and further laboratory characterisation of the organism. The outbreak management function of NCIMS facilitates additional targeted and enhanced surveillance where necessary. Geomapping capability in NCIMS, while currently limited is being developed and will be a useful epidemiological tool.

Where a risk assessment is complex or involves several local health districts, the Communicable Diseases Branch offers advice and coordinates the risk assessment.

Animal health sector

The outbreak management system used by the DPI, the Biosecurity Surveillance, Incident, Response and Tracing (BioSIRT) system, is a relatively new surveillance system with geomapping capability that is being introduced for routine use in most states to record on-farm animal health events. BioSIRT is currently being used in NSW for emergency situations and there are plans to link it with the Wildlife Health Information System (eWHIS), the national real-time reporting system used for wildlife incidents. BioSIRT will also link with other databases including laboratory information management systems for uploading test results (this will be facilitated through the Sample Tracking and Reporting System project), and the NSW Property Identification Codes database which can provide information about a property’s ownership, location and livestock.

Although these surveillance and notification systems are primarily used to record incidents of defined notifiable diseases, eWHIS in the wildlife animal health sector may indicate the occurrence of known or unknown emerging infectious diseases, including zoonoses. The national Wildlife Event Investigations Team may be convened by the Australian Chief Veterinary Officer to support the investigation of emerging infectious diseases in wildlife, including the potential for zoonotic disease.

Response

A zoonotic disease may be detected in the human or animal health sector. Table 3 describes examples of some recent zoonotic disease incidents not elsewhere described in this issue. Timely communication between the sectors during a response ensures coordinated risk assessment and effective management and that the different interests of each sector are addressed.

|

Human health sector

Management of notifiable diseases, including zoonoses, by public health units follows disease-specific protocols found in the NSW Notifiable Diseases Manual.8 For some notifications, the DPI is notified as part of the routine response. Depending on the nature of the zoonosis, the public health intervention may be to disseminate information to the case and others who may have been exposed, or to recommend or arrange treatment or prophylaxis for cases or contacts.

In recent times, the Communicable Diseases Network Australia has recognised the need to harmonise public health responses across all Australian states and territories and this has led to the development of the Series of National Guidelines (SoNGs) for selected diseases. Currently, SoNGs are being developed for Hendra virus infections and for rabies/Australian bat lyssavirus infections and exposures to animals potentially infected with rabies/Australian bat lyssavirus.

Animal health sector

For notifiable diseases the DPI response follows defined national and jurisdictional procedures, and for zoonoses includes liaison with the human health sector. The response to emergency animal diseases may include convening a specific Consultative Committee on Emergency Animal Disease with a representative from the human health sector.

Discussion

The collaborative intersectoral approach to the management of zoonotic diseases in NSW ensures a timely and effective response. Established relationships between key officers in the different sectors are a major factor in ensuring effective communication. Regular joint meetings help ensure that this occurs, and that each agency understands the needs and constraints on the other agencies.

Management of endemic and exotic zoonoses continues to utilise significant resources in both the human and animal health sectors in NSW; this is particularly so for the investigation of foodborne diseases. Recent exotic zoonoses responses have included the provision of post-exposure prophylaxis against rabies for a number of people returning from Bali following dog bites, and the DPI involvement with rabies control projects in Bali. A positive outcome of collaborative management has been the implementation of improved infection control and biosecurity procedures for veterinarians and others associated with animal care and handling. For example, the occurrence of Hendra virus in horses and the fact that the symptoms in horses are not specific has resulted in more horse practitioners using personal protective equipment. It is also now recognised by veterinarians that Q fever is not just a disease of farm animals and that cases have been recorded in companion animals. This has necessitated the need for routine personal protective equipment/infection control use in a wider range of situations.

The following offer the potential to improve zoonotic disease management:

-

The introduction of BioSIRT could potentially enable the collation of real-time reporting in a single national database which will be particularly useful for cross-border incidents.

-

Currently, human and animal health surveillance and laboratory data are held within each sector, but data regarding zoonotic incidents could be shared (e.g. through automated intersectoral real-time alerts).

-

Due to the different interests of each sector in zoonoses, and variable regional incidence, zoonosis notification is inconsistent between and within the sectors, and could be aligned to ensure timely and effective management.

-

Arbovirus monitoring programs are conducted in mosquitoes and animals for each sector in NSW, but are targeted for diseases specific to that sector. There is potential for greater collaboration (e.g. sharing of specimens to look for diseases of interest to the other sector).

Conclusion

A coordinated One Health approach by the human and animal health sectors in NSW provides effective management of zoonoses of public health significance, and ensures the different interests of each sector are addressed. National health reforms and consequent reorganisation of the NSW Health system is likely to change some of the arrangements for delivering public health services in the state. It will be important for both sectors to maintain effective working relationships as the organisational structures within the health system evolve. Particular challenges include detection and management of emerging zoonoses, especially in wildlife, and the changing human–animal interface with increasing urbanisation.

References

[1] NSW Department of Primary Industries. NSW Zoonoses – diseases transmissible to humans. NSW DPI Prime Fact 814, July 2008. Available from: http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/334001/Zoonoses-animal-diseases-transmissible-to-humans.pdf (Cited April 2011.)[2] Australian Government Department of Agriculture. Fisheries and Forestry. Exercise Eleusis ’05 Evaluation Report – Key findings. 2006. Available from: http://www.daff.gov.au/animal-plant-health/emergency/exercises/eleusis (Cited January 2011.)

[3] Australian Government Department of Agriculture. Fisheries and Forestry. Exercise Hippolytus Evaluation Report. July 2007. Available from: http://www.daff.gov.au/animal-plant-health/emergency/exercises/exercise_hippolytus (Cited January 2011.)

[4] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National Pandemic Influenza Exercise – Exercise Cumpston 06 Report. 2007. Available from: http://www.flupandemic.gov.au/internet/panflu/publishing.nsf/Content/cumpston-report-1 (Cited January 2011.)

[5] NSW Department of Primary Industries. Notifiable animal diseases in NSW. NSW DPI Prime Fact 402, 4th ed., December 2008. Available from: http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/114414/Notifiable-animal-diseases-in-nsw.pdf (Cited April 2011.)

[6] Animal Health Australia. Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN). Commonwealth of Australia, 2007. Available from: http://www.animalhealthaustralia.com.au/programs/eadp/ausvetplan/ausvetplan_home.cfm (Cited April 2011.)

[7] NSW Department of Primary Industries. Emergency animal diseases. NSW DPI Prime Fact 588, 2nd ed., November 2008. Available from: http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/121109/Emergency-animal-diseases.pdf (Cited April 2011.)

[8] NSW Health. Notifiable Diseases Manual. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/Infectious/controlguide.asp (Cited April 2011.)

[9] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Health Advice: Interim guidelines for persons working with poultry and other birds at risk of highly pathogenic avian influenza (CDNA, 2008). Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/avian-influenza-poultry-guidelines.htm (Cited April 2011.)

[10] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th ed. 2008. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/Handbook-home (Cited April 2011.)

[11] NSW Government Emergency Management NSW. NSW State Disaster Plan (DISPLAN). 2006. Available from: http://www.emergency.nsw.gov.au/plans/displan (Cited April 2011.)

[12] NSW Health. HEALTHPLAN – NSW. PD2009_008, February 2009. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2009/PD2009_008.html (Cited April 2011.)

[13] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI). 2009. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/panflu/publishing.nsf/Content/ahmppi-2009-l (Cited April 2011.)

[14] Queensland Government Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation. Guidelines for veterinarians handling potential Hendra virus infection in horses. Queensland Department of Primary Industries. Available from: http://www.dpi.qld.gov.au/4790_13371.htm (Cited April 2011.)

[15] Australian Veterinary Association. Guidelines for Veterinary Personal Biosecurity. June 2011. Available from: http://www.ava.com.au/biosecurity-guidelines (Cited June 2011.)

[16] NSW Government Emergency Management NSW. NSW Animal Health Emergency Sub-plan: A Sub-plan of the NSW State Disaster Plan. December 2005. Available from: http://www.emergency.nsw.gov.au/content.php/545.html (Cited April 2011.)

[17] NSW Government Emergency Management NSW. NSW Environmental Services Functional Area Plan (Enviroplan): Supporting plan to NSW Disaster Plan. November 2005. Available from: http://www.emergency.nsw.gov.au/content.php/561.html (Cited April 2011.)

[18] Office of Environment and Heritage. Policy and procedures for the identification and management of wildlife disease. May 2009.