Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, May and June 2009

Communicable Diseases BranchNSW Department of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 20(8) 133-139 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB09019

Published: 7 September 2009

Abstract

For updated information, including data and facts on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Public Health then Infectious Diseases, or access the site directly at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp.

Figure 4 and Tables 1 and 2 show reports of communicable diseases received through to the end of June 2009 in New South Wales (NSW).

|

|

H1N1 influenza 09 (human swine influenza)

Cases of what eventually turned out to be H1N1 influenza 09 (human swine influenza) were initially reported in Mexico and North America in April 2009. In response, Australian health authorities implemented a range of interventions designed to:

-

delay the entry of the novel strain of influenza into the country; and

-

contain its spread.

On 17 June – when it was clear that community transmission was occurring in parts of Australia – the approach was changed to protecting those most vulnerable. Free anti-influenza medicine has been made available via general practitioners and influenza clinics to patients with influenza-like illness who:

-

have chronic medical conditions that place them at higher risk of severe disease

-

are pregnant

-

are Aboriginal

-

have moderate to severe disease.

The situation continues to evolve. For updated information see: http://www.emergency.health.nsw.gov.au/swineflu/index.asp.

H1N1 influenza 09 and cruise ships in NSW: preliminary report

Introduction

In April 2009 a novel influenza strain, H1N1 influenza 09 (human swine influenza or H1N1) began to circulate around the world. Public health efforts initially focused on delaying the entry of the virus into Australia through a range of measures, including an education campaign asking travellers returning from affected countries to present to their local emergency department should they develop symptoms of influenza, enhanced measures at airports to assess returning travellers for illness, testing and isolation of possible cases, and quarantine of people in close contact with patients who tested positive for the illness. These measures successfully limited the introduction of the virus into NSW for many weeks.

In May 2009, two outbreaks of influenza were identified on cruise ships docking in Sydney. Here we report on the public health response to these outbreaks.

Cruise ship 1

In May, crew on the Dawn Princess cruise ship reported to the Australian Quarantine Inspection Service (AQIS) that a small number of passengers had tested positive for influenza A at the ship’s clinic. While the clinic was able to perform rapid testing for influenza A, it could not determine whether the influenza A detected in passengers was H1N1 or seasonal influenza. AQIS reported this information to NSW Health the morning the ship docked in Sydney. As the cruise had included a visit to Hawaii – in a country known to have community transmission of H1N1 – NSW Health considered that there was a reasonable risk that some of the sick passengers could have H1N1. At the time, no community transmission had been identified in NSW, so a precautionary approach was taken to minimise the risk that the virus would be introduced into the state.

Discussion with the ship’s doctor revealed no evidence of an outbreak of influenza-like illness onboard. Following consultation with the Australian Department of Health and Ageing, NSW Health arranged for a public health team to board the vessel and assess the situation. Passengers with respiratory symptoms were asked to attend the ship’s clinic for assessment. Only four had symptoms consistent with influenza. Urgent tests were completed to determine whether any of these passengers had H1N1. Had this been the case, sick passengers and crew would have been isolated and others placed into quarantine to prevent the spread of the virus into the community. However, the tests returned negative and the passengers and crew were allowed to go about their business that evening.

Cruise ship 2

A day later, crew on another cruise ship – the Pacific Dawn – also reported to AQIS that a small number of passengers had tested positive to influenza A. Again, NSW Health made a careful assessment of the risk: the ship had not visited any ports where H1N1 was circulating, and none of the ill passengers had been in countries known to be affected by H1N1 prior to boarding. As there were no grounds to suspect the virus was aboard the ship, NSW Health, in consultation with the Department of Health and Ageing, allowed passengers and crew to disembark as usual, following completion of a Health Declaration Card (HDC).

As part of its enhanced public health surveillance for H1N1, NSW Health couriered samples from ill passengers for urgent testing. These were found to be positive for H1N1 later that day. NSW Health immediately began contacting all passengers who had reported illness on their HDCs, asking them to remain in isolation either at home or at their hotel for 7 days. It was believed that these passengers would be at greatest risk of transmitting H1N1 to others. The Department of Health and Ageing agreed to contact other passengers to ask them to stay in quarantine for at least 7 days. NSW Health worked with media outlets to alert passengers who had dispersed, issued a statement on the NSW Health website and set up an information telephone line.

Comment

These two outbreaks of influenza on cruise ships were carefully evaluated and decisions were made based on the facts at hand. At the time, Australia was attempting to contain any spread of the virus into the community in order to learn how severe H1N1-related disease might be, and what measures might be needed to control it. Public health actions such as isolation and quarantine limit the liberty of thousands of people and must not be undertaken lightly.

The measures put in place soon after the emergence of H1N1 included screening at international borders for people who had been in countries where the new virus was circulating. Where such people arrived by air into Australia, the travel time was usually too short for the virus to have circulated and caused infection among passengers. However, the situation on ships is different: cruises can last weeks – long enough for multiple generations of influenza to develop.

Several limitations emerged from the response to these outbreaks. Some of those affected reported that they would have liked clearer communication about what was happening to them and what they were required to do. Many reported inconvenience and costs due to missed travel arrangements and inability to leave home. Although the Department of Health and Ageing had developed plans to contact and place into quarantine passengers who were potentially at risk but reported no illness on their HDCs, it took a few days to do so. Quarantine packs (containing masks, hand gel and other materials) were, in some cases, slow to arrive. The national automated call back system for people in quarantine could not easily be turned off for passengers that came under the care of NSW Health. Passengers in isolation and quarantine reported receiving multiple calls from different people, resulting in repetition and confusion. The sheer volume of laboratory testing performed in the early days of the outbreak challenged laboratory capacity, leading to delays in turnaround times and results.

NSW Health subsequently interviewed a sample of passengers who were on the Pacific Dawn to further understand the problems encountered. Analysis of these and other issues will contribute to an improved response in the future.

Despite these concerns, passengers and crew from the Pacific Dawn cooperated with public health advice and the measures worked: the outbreak aboard the ship was contained (Figure 1) and did not contribute to a broader outbreak in the Australian community.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in NSW, 2008

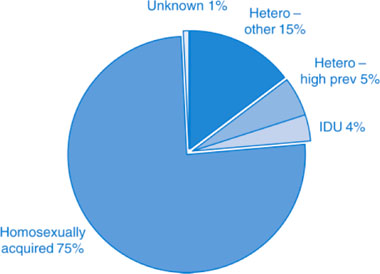

HIV disease remains a major concern; however, new diagnoses have remained fairly stable in NSW in recent years. In 2008, 322 people were newly diagnosed with HIV infection in NSW, including 290 males and 32 females. Cases’ ages ranged from 13 to 75 years. Most cases (75%) were reported to be homosexually acquired, 20% were reported to be heterosexually acquired and 4% were reported to be acquired through injecting drug use (IDU). One percent of cases did not have their exposure reported (Figure 2). Here we report some of the epidemiological features of these cases.

|

Methods

Under the NSW Public Health Act 1991, laboratories report all confirmed HIV infections to NSW Health and a questionnaire is sent to all notifying doctors to collect epidemiological information on cases. In 2008, additional follow-up resulted in more complete information and improved classification of cases.

Tests conducted

In 2008 in NSW, 636 HIV-positive tests were reported from reference laboratories. Of these, 322 were in NSW residents newly diagnosed with HIV. Of the remaining 314, a total of 226 were repeat tests of previously confirmed cases, 64 were for cases previously diagnosed either overseas or interstate, and 24 were for cases residing overseas or interstate.

Homosexually acquired HIV

Among the 322 new cases in NSW in 2008, 243 (75%) were reported to be homosexually acquired. Most (71%) were residents of central and south-eastern Sydney and 63% were Australian-born.

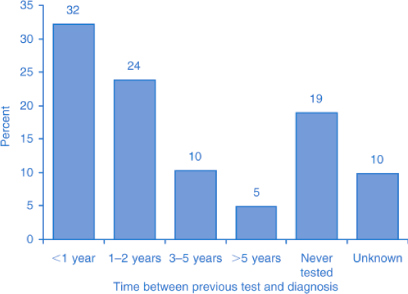

Only a third reported having had a previous HIV test in the last year and 19% reported never having had a test before (Figure 3). Almost half (45%) had evidence of recent infection (i.e. either a negative or indeterminate HIV antibody test or a seroconversion illness in the previous 12 months). However, 10% (24 cases) had evidence of advanced disease at time of diagnosis (CD4 count <200 or an AIDS-defining illness within 3 months of HIV diagnosis). While the median age of patients with advanced disease was 41 years, patients with recent infection were evenly spread across their 20s, 30s and 40s.

|

Heterosexually acquired HIV

Of the 322 new cases, 65 (20%) were reported to be heterosexually acquired. Of these, one-quarter were born in high prevalence countries who reported heterosexual sex with a partner from a high prevalence country. Nine were female and eight were male. Most were likely acquired outside Australia. One-quarter presented early and one-quarter presented late in their infection.

Of the remaining three-quarters of people with heterosexually acquired HIV infections, 28 were males, 19 were females and half (49%) were Australian-born. There was no geographic clustering of these cases. Of these, 19% were diagnosed early and 23% late.

HIV acquired through IDU

There were 12 cases of HIV reported to be acquired through IDU – eight males and four females. Nine were Australian-born. There was no clustering by age or geographical location.

Conclusion

The number of HIV notifications in NSW remains stable. Homosexual acquisition is the most common exposure for HIV infection and highlights the importance of promoting safe sex practices and regular testing among this group.